|

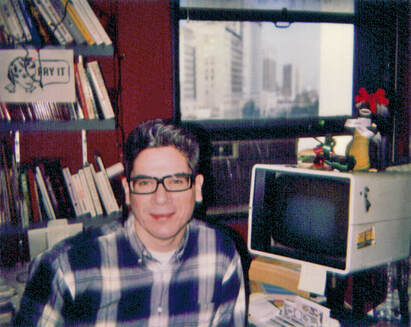

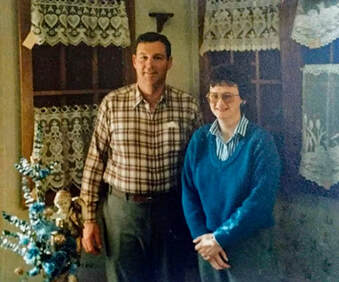

With in-person author events still on hold indefinitely, I'm devoting one blog post each month to an author interview. This month's interview is with Janet Glaser, who writes as J.Q. Rose. Her mysteries, Deadly Undertaking, Terror on Sunshine Boulevard and Dangerous Sanctuary, released by Books We Love Publishing, offer readers chills, giggles, and quirky characters. After presenting workshops on Writing Your Life Story for several years, Janet decided to take her advice and pen her memoir, Arranging a Dream: A Memoir. The book is scheduled for release January 1, 2021, also from Books We Love Publishing. Arranging a Dream tells the story of how Janet and husband Ted, budding entrepreneurs with more enthusiasm than experience, purchased a floral shop and greenhouses in 1975, where they planned to grow their dream. Leaving friends and family behind in Illinois and losing the security of two paychecks, they transplanted themselves, their one-year-old daughter, and all their belongings to Fremont, Michigan, where they knew no one. Through trials and triumphs, Janet and Ted dug in to develop a blooming business while juggling parenting with work and keeping their marriage thriving. To celebrate the Arranging a Dream: A Memoir Winter Virtual Book Tour, Janet is offering a free eBook to a lucky reader. Just leave a comment below to be entered in the drawing. Deadline for entries: Sunday, December 20, 9 pm Eastern Time. How is writing about real people, places, and events different from writing fiction, where you can invent characters, situations, and settings? Are the two processes similar in any ways?

In the acknowledgments, you mention that you and your husband Ted had fun recalling the times you write about in this memoir. Tell us more about how your memories meshed and how you reconciled differences when your memories of a specific event didn’t match.

What other techniques did you use to access the memories that helped you tell this story?

What do you hope readers will take away from Arranging a Dream? What did you gain by writing the book? I hope readers will be inspired to work toward their dreams. Use their passion to keep driving toward the future they envision. Looking through the lens of time allowed me to put myself into the shoes of the previous owners of the flower shop, Hattie and Frank. After owning the business for so many years and deciding to sell it, I discovered I was like Hattie. We disagreed a lot with Hattie about how to run the shop and greenhouses because we wanted to use our new ideas and not listen to the tried-and-true methods she had developed during her years of experience. She was afraid we would fail by being so bold. I never thought I would admit I acted like Hattie when we sold our shop. I was also fearful the new owners would fail if they didn’t follow our ways of running things. Instead, they have been successful and are still in business. In addition to your own writing, you’re committed to helping others tell stories from their lives, through your Facebook group, your interactive journal, Your Words, Your Life Story: A Journal for Sharing Memories, and your workshops. Why is this important to you, and what are the rewards?

What’s next? Are there other periods of your life that might lend themselves to a memoir? Or will you write more fiction? Next, I hope to turn the book, Your Words, Your Life Story, into a course so I can reach more people and encourage them to write their stories, because I am a life storytelling evangelist. I always have ideas for stories swirling through my brain, so I will be writing, but I have not chosen which idea to develop at this time. I am just savoring touring around cyberspace, meeting authors and readers. Anything else you'd like to add? Thank you, Nan, for hosting me during the Arranging a Dream: A Memoir Winter Virtual Book Tour!

16 Comments

With most in-person author events still on hold indefinitely, I'm devoting one blog post each month to an author interview. Today's guest is Donald Levin, author of seven mysteries in the Martin Preuss series, as well as the novel The House of Grins (1992) and two books of poetry, In Praise of Old Photographs (2005) and New Year’s Tangerine (2007). The latest book in the Martin Preuss series, In the House of Night, officially launches Tuesday, October 6. You have published six books in the past nine years, with a seventh due out soon. What writing (and other) habits contribute to your productivity?

My experience taught me that if you’re going to be a writer, you need to approach it as a profession. You can’t sit and wait for inspiration, any more than a surgeon can wait to be inspired before performing an operation. You have to make yourself write, even if you don't feel like it. Inspiration and creativity come from writing, not the other way around. Once I started as a serious creative writer—producing novels, short stories, and poetry—I transferred that workmanlike attitude and those work habits that I developed. So when I’m working on a novel, I make sure I’m at work at the same time every day, and put in a full day of writing with a quota of 1,000 words. I’m very fortunate that I was able to retire from teaching five years ago so I have been able to devote a lot of time to writing. But even before I retired, I made time to write while working full-time. It can be done. According to your website, you have worked as a warehouseman, theatre manager, advertising copywriter, scriptwriter, video producer, and political speechwriter as well as professor and dean at Marygrove College. How does this varied work background serve you as an author?

And second, I get bored easily (the polite way of saying the same thing is, I have always been intellectually restless) so I’ve always wanted to be as versatile as possible. This not only helped me find work because I could do a lot of different things, but having all those different kinds of jobs kept me learning new things and figuring out how to explain them to other people. That’s one of the things I most love about writing: I’m constantly learning new things. Your Martin Preuss series is set in Ferndale, Michigan. How important is setting to your stories, and what made you choose Ferndale?

I chose Ferndale mostly as a matter of convenience: I live there. When I want to scout locations, I can just walk around to soak up the sights and sounds. I like to say that people can walk around with any of my books in their hands and see where the locations are. There’s also another reason why I chose Ferndale: one of my favorite writers is Henning Mankell, who set his mystery series in Ystad, a small city in Sweden. As it happens, Ferndale is almost exactly the same size as Ystad, so I feel like I’m making an homage to Mankell by giving my detective a beat similar to Mankell’s Wallander. What goes into creating a fictional character for a series? Are there any differences with creating a main character for a stand-alone novel?

So when I started the first Preuss novel, I had planned (or hoped, I should say) that it would be part of a continuing series. As I’ve written the books, Preuss has sort of unfolded himself to me as a character, and I’ve gotten to know him better and better—and my readers have, too. Another important aspect of writing the Preuss series for me and my readers is Preuss’s son, Toby. Toby is multiply handicapped and lives in a group home, but he is an integral part of Preuss’s life. Indeed, the relationship between Toby and his father is, in my humble opinion, at the heart of the series. Martin Preuss loves his son fiercely and cares for him with great tenderness, and Toby returns the love unconditionally. One reviewer called their relationship “a touching element that’s a constant in the series”; another reviewer noted, “The complexity of the main character and especially his deep love for his handicapped son draw the reader into the story in a way that few other mysteries do.” Toby has profound physical and cognitive disabilities, but the character is sweet, loving, joyful, and everybody’s favorite character in the books. (Also one of the few rounded, sympathetic portraits of handicapped characters I’ve seen.) Toby is based on my own grandson Jamie, who sadly passed away a few years ago; writing him as a continuing character in this continuing series gives me a chance to keep that wonderful young man alive for me and everyone who knew him. What would you like HeartWood readers to know about your mystery series and especially the soon-to-be-released In the House of Night?

Each book uses its crimes as a starting point for examining larger crimes and more significant social issues. The latest book, In the House of Night, perhaps most overtly deals with contemporary social and political concerns. The book emerged from my growing concern with the spread of white nationalism in this country. Set in 2013, the book looks at how the white nationalist movement began to edge into the mainstream of American culture. Here's the story: When the police investigation into the murder of a retired history professor stalls, friends of the dead man plead with PI Martin Preuss to find out what happened. The twisting trail leads him across metropolitan Detroit, from a peace fellowship center, a Buddhist temple, and a sprawling homeless encampment into a treacherous world of long-buried family secrets where the anguished relations between parents and children clash with the gathering storm of white supremacist terrorism. You typically divide your time between Michigan and Florida. Do your writing habits and routines change with a change of location?

Have you found it harder or easier to write during the COVID-19 pandemic? How has COVID-19 affected the way you interact with readers? As I mentioned in the last question, the pandemic quarantine made me rearrange my writing schedule a bit. And it’s played havoc in connecting with readers in books fairs and exhibits . . . they’ve all been cancelled this year. It’s made me rethink how I connect with readers. I always hold book launch parties for each new book with music, refreshments, readings, and so on. This year, out of concern for bringing people together, I’m organizing a virtual book launch for In the House of Night. It’ll be on my Facebook page (and Youtube, if I can figure out how to do it) on Tuesday, October 6, from 7 till 8 p.m. All writers have to deal with discouragement and doubt at times. How have you dealt with those negative emotions?

This writing life must not be for me, I decided. I’m just not good enough. Don’t have what it takes. So I gave up writing fiction. It was painful, even devastating. I had failed at the one thing I had wanted to do since I was little. But I still thought I had some chops as a writer, just not a fiction writer; I had already had several writing jobs, as I mentioned previously. I turned away from literature entirely; I turned away from reading. Instead I became the professional writer I described in my response to your first question. And I did well in that world. It came to pass that the writing I was doing for others relit that little holy pilot light. I started thinking about returning to fiction, and about writing under my own name. About the importance of stories in our lives. About the need to do it. In the gap between my fleeing from imaginative writing and returning to it—a ten year gap—I grappled with what success as a writer really meant, and more importantly what it wasn’t. I met editors, and became an editor myself, and realized how capricious and unpredictable the process really is. With the confidence I had gained, and with what I had learned about writing, I came through that decade of despair by learning that the writing itself and the changed qualities of mind and heart that accompany writing really are more important than the approval suggested by acceptance by others. As if that insight broke some self-imposed spell, in the years since I’ve published eight novels (seven in the Martin Preuss mystery series), two novellas, two books of poetry, a handful of stories, and dozens of poems in print and online journals. That voice shouting in your ear, the voice a friend of mine personifies as “Sid”—Self-Inflicted Doubts—never goes away. But with practice and wisdom, you can silence it long enough to get some good work done. And in the end, that’s really all that matters. Anything else you’d like to add? Many thanks for some great questions! I appreciate the opportunity to appear here. Find Donald Levin and his work here:

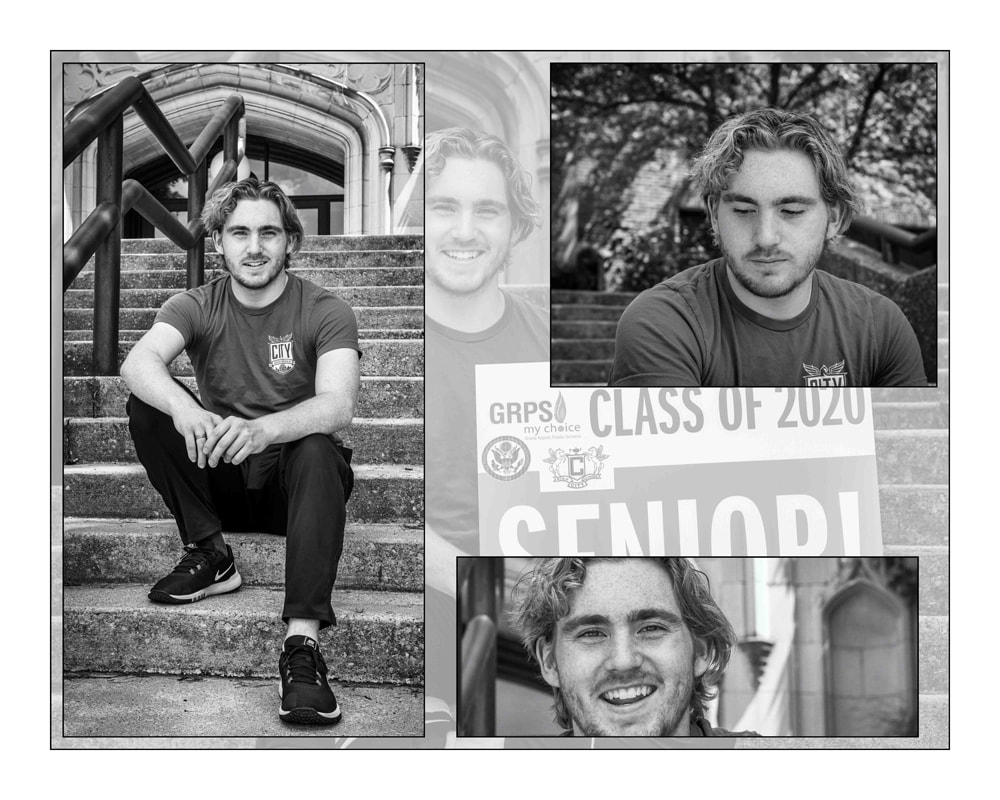

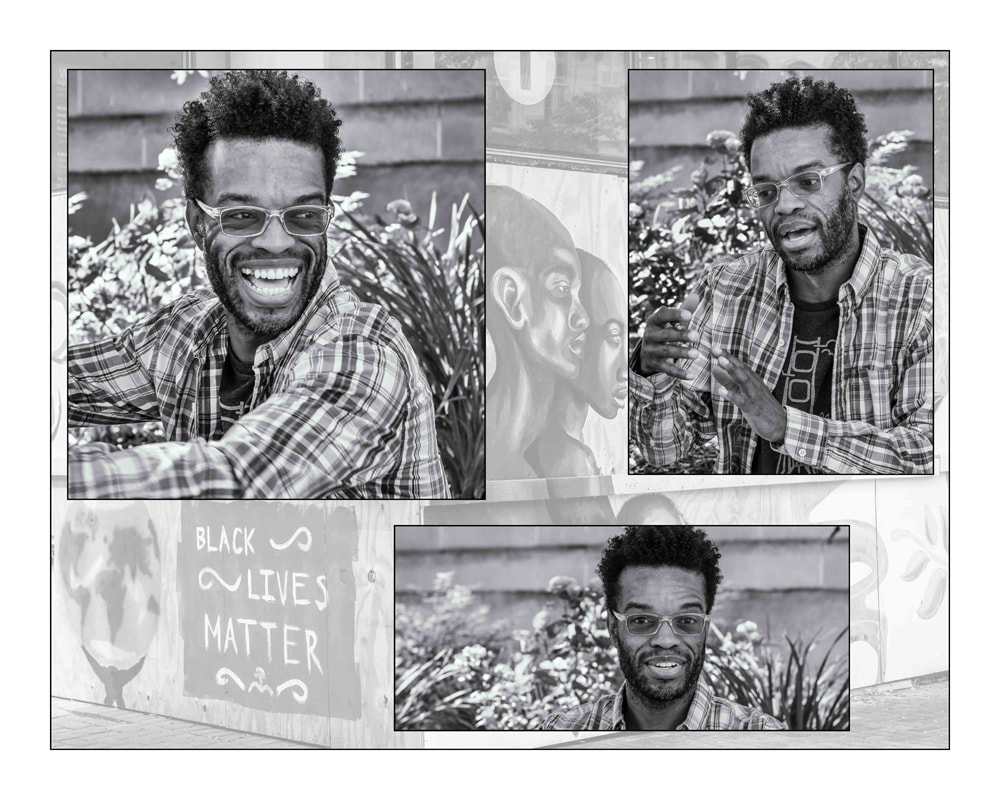

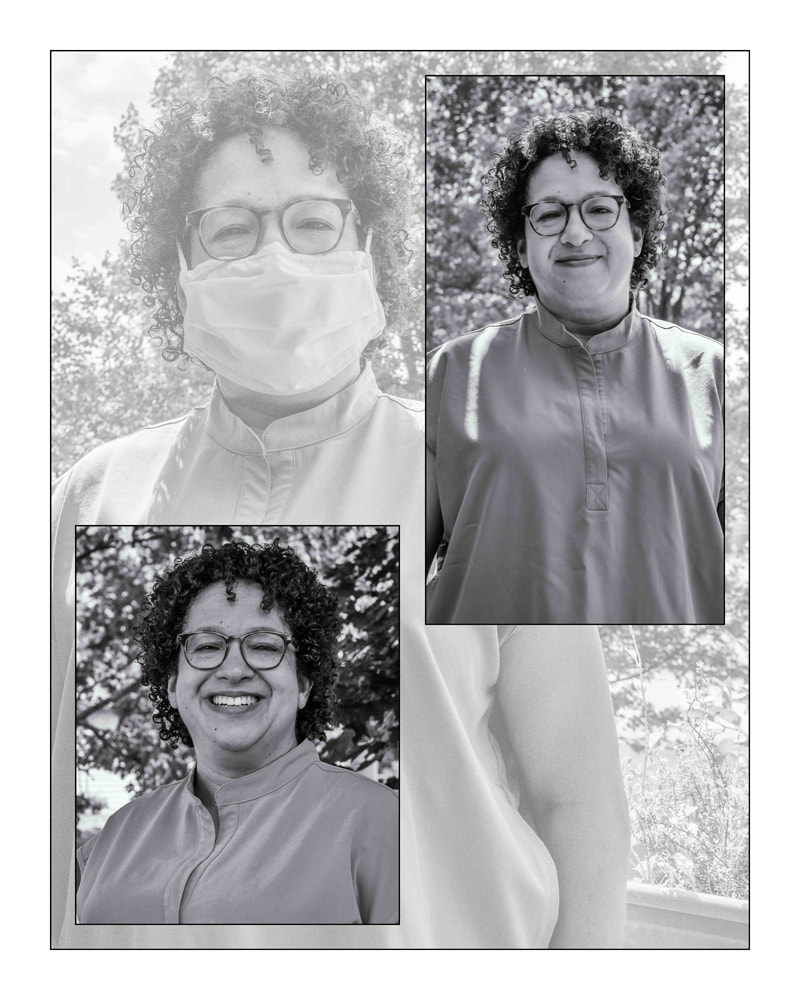

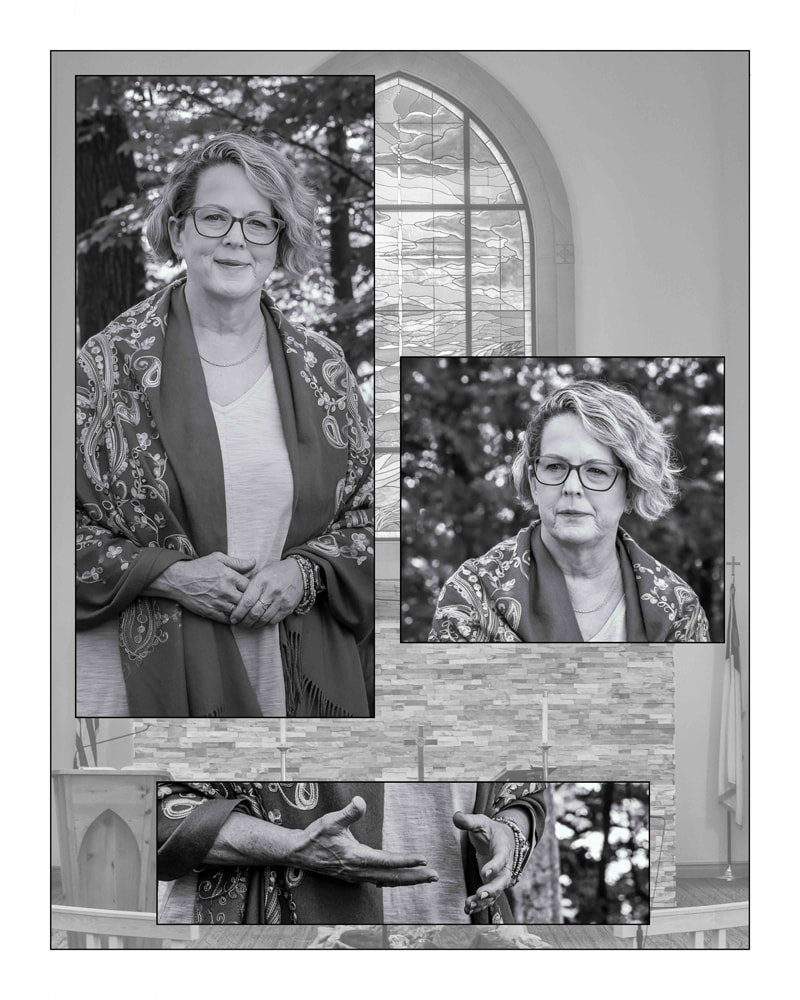

Website: www.donaldlevin.com Blog: www.donaldlevin.wordpress.com Amazon author page: https://amzn.to/32y8bLw Twitter: @donald_levin Instagram: Donald_levin_author Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Donald-Levin-Author-121197194659672 These challenging times can be both stimulating and stifling to creative types. Some writers and artists I know have found comfort in their work; others have been unable to summon their muses and have turned to other activities for solace. I say, whatever works! These times are exceptional, and as I recently read in an article a friend sent me, “During this extraordinary time, we have to realize that everyone now has an additional part-time job that might be called Citizen of the Covid-19 Pandemic,” and we need to give ourselves credit for the time and energy that extra work takes.  Gail Howarth Gail Howarth One artist who's managed to do inspired and inspiring creative work while coping with the pandemic is photographer Gail Howarth. Regular readers of HeartWood may remember seeing Gail featured here a couple of years ago. At that time, she was working on a photography/writing project with Mel Trotter Ministries, a Grand Rapids nonprofit organization that works with homeless people. Now, she is once again combining photography and writing to call attention to today's pressing issues, which include but are not limited to COVID-19, essential workers, race and racism, and LGBTQIA community concerns. What led you to undertake this project? City Center Arts in Muskegon offered me the opportunity to be the featured artist there from September 1 to October 10. The gallery has been very supportive of me, my nature and landscape photography, as well as another project I am working on called The Gratitude Project By Lakehouse Photo. Originally we were going to feature The Gratitude Project. However, the rest of the exhibit will honor essential workers. We felt that gratitude, while a worthy topic, might seem insensitive to those that have sacrificed so much. We thought about postponing the featured artist wall or displaying my landscapes. But I felt like we were missing the opportunity to do something meaningful. The year 2020 has been challenging. The pandemic, racial tension and rioting, and a divide that grows deeper daily in our nation weigh heavily on my heart. I just kept thinking, this is a time to heal, not to fight amongst one another. When I proposed A Time To Heal to the folks at City Center Arts, they quickly agreed to the project. Christina once asked herself, Am I Black Enough? Later in life, as she experienced racism in many forms, the answer became clear. Christina expresses her concerns, her anger, and her wisdom by blogging and through dance. How did you find people to participate? Were most readily willing, or did you have to persuade some? I asked everyone I knew if they would participate, and then they asked everyone they knew. I posted requests for participants on my Facebook and Instagram pages and even contacted local social justice organizations. Most of the participants were referred through the gallery or Facebook friends. Of the 17 participants, I knew less than one-third personally. I received a lot of non-responses to emails and phone calls. However, those that expressed an interest in the project showed no hesitation about participating. Everyone felt like it was an important project and wanted to be involved. Like so many others 2020 grads, Chauncey lost the opportunity to complete his senior year of high school in person and to experience senior prom, skip-day, an actual graduation ceremony, and more. Read more about Chauncey here. How do you think communicating these varied stories and images can promote healing, both for individuals and for our country and world? In a nutshell, we need to get to know one another. The project gives folks from various backgrounds the opportunity to share their journey with people that are generally not a part of their community. Once we find common ground, it will become easier to communicate about and resolve tough issues. One example from the project would be that there has been immeasurable conflict related to wearing a mask to keep COVID-19 from spreading. There are many reasons stated, but I believe the biggest factor is that folks don’t know anyone that has had it, and therefore, it does not seem real. Three of the participants of the project have had COVID-19. Though all three have recovered, they struggle with ongoing health issues. One person caught the virus from a man that did not survive. Another worked in one of the hardest-hit hospitals in the Detroit area. She witnessed countless deaths every day. All three encourage everyone to wear a mask. Once you know someone that has had the virus, you will likely not question whether mask-wearing is right or wrong. Healing begins one person at a time. Hopefully, healing begins with one person, then a second and a third, and multiplies and impacts a whole community, a state, a nation, and beyond. Healing can be hard work and take years. But it can also be quite magical. Have you ever had a rigid belief about a thing and then learn one new fact about it, and it shreds everything you ever believed? I do hope that folks will find a few magical moments from the exhibit and blog posts. I don’t believe my project alone can make a profound change in the world. I do think that projects with the same or similar intentions are popping up all over as a reaction to the dysfunction we are currently experiencing. I hope that collectively change can and will happen. Lastly, I will admit that there was a moment during the early part of the project that I became disillusioned. Not all of my friends or family felt the project had merit. They thought that the result might create greater divisiveness versus the desired outcome of healing. I shared with one of the participants that my heart was a bit broken by the response. I asked her earnestly, what if the only heart opened or healed was my own. Her response was: Well, then the whole project is worth it. I am grateful, and I cherish her words. Working as a respiratory therapist at one of the hospitals hardest hit during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cindy contracted COVID-19. Now recovering, she asks that everyone wear a mask. In the introduction to “A Time to Heal” on your blog, you write about parallels between the present day and the 1960s. What similarities and differences do you see between the two times? Now and then, social unrest led to demonstrations and rioting. In the ’60s, the issues were related to civil rights, the feminist movement, the Viet Nam War, and the gay liberation movement. Today, we face the same problems and more, but the war we are fighting is with one another. Also, in the ’60s, people still had faith in our government, that our voices would be heard, and that real change could happen. Today, we have lost faith in leadership and our government, that our voices, no matter how loudly we cry, fall on deaf ears, and there is little hope for change. Kwame uses his sense of humor and insight to elevate awareness related to racism and the Black Lives Matter Movement. Kwame believes we are fundamentally bound together and that together we must find a way to get along. In your interviews with this broad spectrum of people, have any common themes emerged? The commonality would be the need or desire of the participant to tell their story or to be heard. All felt that in doing so that it might, in some small way, make a difference. Susan Bishop, MD, is a pediatric doctor. As COVID-19 has significantly changed patient care, she misses children's hugs and unmasked smiles. In an email, you wrote, “The creative process is funny for me. I never have a clear picture of what something will be in the beginning. It just morphs into what it becomes.” In what ways was that true for this project? First, I had no idea if I could pull off this project. I had two months during a pandemic to find people willing to be photographed, to share their stories, and translate them into an exhibit of words and images. Initially, I thought I would display one photograph and a few keywords of each person to convey the story. However, I could not come up with a smart way to show the words. In the end, I decided to label the images more traditionally. Each piece has a name and just a little information about the participant. Hopefully, viewers will become curious enough to read more about the participants on my blog. Then, as I selected and edited photos, I realized that for most participants, a single image left the story incomplete. I began mounting three to five images into a template with a plain white background. The stories were coming together, but still, something was lacking. One day, I accidentally placed one of the photos behind the others. It was fabulous!! I reduced the grayscale of the background image (made it lighter), and it became part of the story. In some cases, I had to backtrack to find and photograph backdrops that would complete the story. Lastly, I initially had a narrow concept of who should participate. The expansion happened naturally and felt right. When Justin learned personal protection equipment was in short supply, he came up with a plan that included renting the second largest cargo plane in the world and having it flown to China, filled with supplies, and flown back to Ohio to begin distribution. He then purchased US-made mask-making equipment and started production in Ohio. How has this project affected you personally? Deeply and on so many levels. There were many days that I felt hopeless. The division between people feels as if it grows larger every day, and I did not feel as though I was working fast enough or hard enough. But I came to believe that I am doing what I can to be a positive force for awareness and change. I will, in some way, continue the work that has begun with this project. I am honored and humbled that complete strangers would take the time to share their life experiences with me. Their words forever change me. The most life-changing aspect of the project is related to racism. I have never considered myself a racist. But, I have become more aware of the cultural bias that I carry with me. I listen with new eyes and ears, and feel with a heart more open. And, as those old untruths pop up, I look them over and toss them away. We have so very much to learn from one another. I am a forever student, and can barely wait for my next teacher. Siena is working toward awareness and social change as a member of the Sunrise Movement, an organization that seeks to remove oppressive and unsustainable systems to create a just future. What is your hope for this project and its impact? I hope that hearts and minds will be changed, that we will become a more unified people, even if we disagree, and as a result, create a better future for our children. That is a pretty big hope, isn’t it! I am not sure if it is realistic at all. But, in the words of John Lennon, “You may say I'm a dreamer, but I am not the only one.” I hope others will be inspired to start projects that promote healing and unity. Pastor Sarah believes it is time to put an end to our differences based upon race, learn to imitate the Kingdom of Heaven, and to live as one. Read more about Pastor Sarah here. A Time To Heal will be on display at City Center Arts from September 1, 2020, until October 10, 2020. Hours are limited, so please check the website before traveling to the gallery. Blog posts related to the participants are located at https://lakehousecc.com/living-at-the-lakehouse/

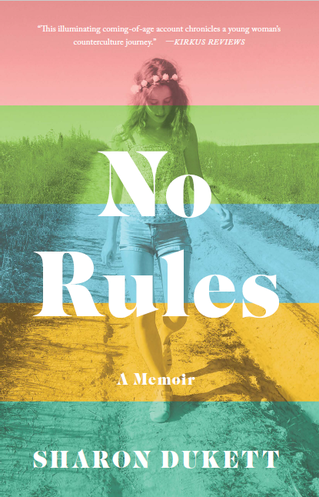

Not all blog posts related to the project are complete. Consider subscribing to be notified of new posts. With in-person author events still on hold indefinitely, I'm devoting one blog post each month to an author interview. This month's interview is with Sharon Dukett, author of the memoir No Rules. Desperate to escape the stultifying life she saw ahead for herself in the early 1970s, and entranced by the California hippie scene, Sharon ran away from home at sixteen. No Rules details her precarious journey through the counterculture, an experience that would mold her into the strong woman she became. Every teenager who ever lived probably fantasized about running away from home and living on their own, but most of us lacked the courage and motivation to pull it off. What do you think made the difference for you?  Sharon in 1970 Sharon in 1970 I was miserable with the prospect of what was ahead for me if I didn’t go. My mother seemed so unhappy, as did my older sister. Leaving wasn’t just for me. It was as though I was breaking out for them, too, demonstrating it was possible to live a different life. Plus I had my older sister with me when I left, which made me feel protected. The catalyst for that leap was being dumped by my first real boyfriend, which left me feeling empty and hopeless. It took a different kind of courage to decide to share your story—a story that you had kept to yourself for a long time. What gave you that courage? As I read writers like Mary Karr and Cheryl Strayed, I saw that what made their books shine was the honesty. They had great stories, and I knew I had a good story, too. But it would be empty if I didn’t share my deepest thoughts and feelings, good or bad. My success and sense of accomplishment in my career and my personal life as I grew older made me strong enough to share my story regardless of others' reactions. In the Epilogue, you mention that you began writing as a way of healing from unresolved hurts. At what point did the book transition from personal writing to something you wanted to share with others?  It quickly transitioned as I got caught up in the memories of the times. I had always wanted to write a book, but when I was younger I never knew what to write about. Once I began writing about this, I didn’t want to stop. But until I had a personal computer, the idea of using a typewriter was overwhelming. If the personal computer had not been invented, I would have never been able to complete a book. In No Rules, you write honestly about some difficult subjects. What parts of the book were most challenging to write? I found one of the most challenging subjects was writing about falling in love with someone that I later came to despise and recognize as a con artist. I had to recapture the naïve innocence I felt at the time and block out what I knew would come later. It was difficult remembering being attracted to him as he later repulsed me. Were there parts you especially enjoyed writing?  Hitching across Canada Hitching across Canada There were some parts that just flowed out of me like they were already written, and I was just the conduit putting the words on paper. I cried through writing the scene with Cindy after she finds Jesus. And the trip across Canada could have been an entire book alone. It was much longer in the original draft. Reliving those memories were like re-experiencing the trip. What helped you access the memories that form the basis of No Rules?  Venice Beach Venice Beach Because this was such a momentous time of my life, much of this was deeply ingrained in my memory. I even believe I recall some exact dialog. I did write the entire first draft in the 1990’s when it was all fresher in my mind. I have some photographs from the time that I used for reference. For example, I have a group shot of those on the ride from Patterson, NJ to Ohio, and photos of our room at the A-House in Provincetown. I also found the more I wrote, the more the memories would overtake me. When you are writing memoir, you take up residence in that time and place and the images and experiences flood back at you. I also played music I listened to during that era, particularly if it was music I don’t often hear. I loved what you wrote in the Epilogue about the people from that time in your life being your “first tribe.” How did they function in that role?  Yurt building Yurt building Despite some of the bad things that happened, we were all part of a larger community. No matter where you went, you could easily connect with others because they looked like you. I learned so much from all these people because our backgrounds were highly diverse. It didn’t matter what socio-economic, ethnic or religious background you came from—no one cared, and no one typically asked. I don’t think that has ever happened in America before or since. You can’t live through a time like that and not recognize the common humanity in all of us. Once you’ve seen it, you can’t un-see it. In the acknowledgments you say the book is an accumulation of years of work. Take us through your journey from initial idea to publication. How long did you spend writing and revising the book? What avenues did you explore in pursuing publication? How did you come to be published by She Writes Press?

You also mention that you belonged to a writer’s group. What did you find valuable about that experience? Were there any challenges?  Sharon with Ernie, 1972 Sharon with Ernie, 1972 I spent several years in the writers group. I don’t think I was always open to the input from some of the members, probably because of how it was presented. But generally speaking, even those that came across as being overly critical had truth I could learn from. In time we modified our process for critique so we had to start out with three or more positive comments first before any negative comments. This was better for all of us because writers need positive reinforcement of what works along with knowing what to improve. It was fairly time consuming as there were four or five of us turning in lengthy chapters for review every two weeks. I know my chapters tended to be 7,000 or 8,000 words each. They were all cut a lot when I revised later on. I stayed in that group until I put the work aside in 2000. What do you hope readers will take away from No Rules?  Sharon with her older sister Anne Sharon with her older sister Anne I want readers to experience what it was like to live in those times, and the transformation that came about as a result of discovering feminism and growing my own strength. What did you gain by writing the book? By writing this book, I have completed a goal I had for years, and often wondered if I would ever reach. By doing so, I was able to preserve a unique time in history that no longer exists and will always be part of who I am. What’s next for you as an author? I am currently working on a thriller novel that takes place in the near future when climate science has been declared to be illegal propaganda in the US, and activists are detained and disappear. Anything else you’d like to add? One of the greatest experiences of being a writer that I never expected, particularly now because of social media, are the wonderful writers I have met and connected with online. My new tribe is made up of writers who are supportive of one another and offer support and information. We inspire each other and help one another reach our goals. I have discovered I am once again part of a larger community.

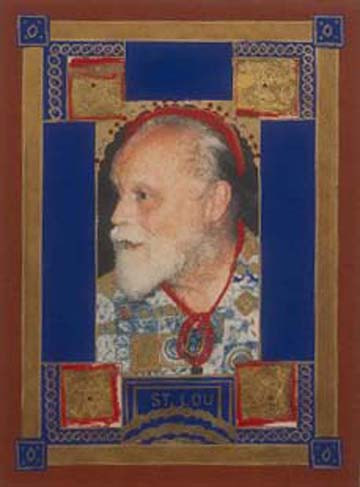

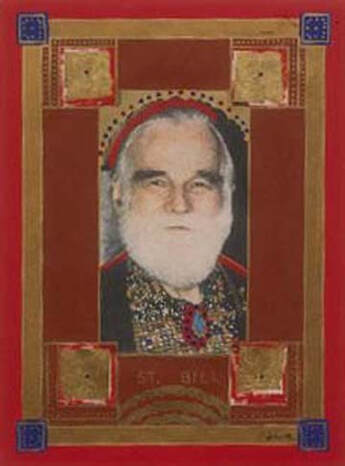

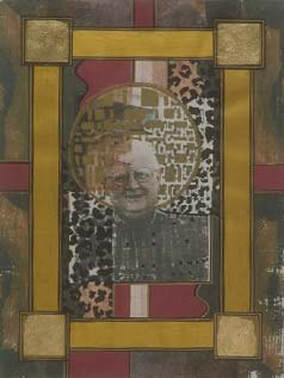

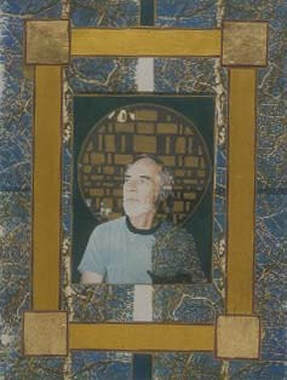

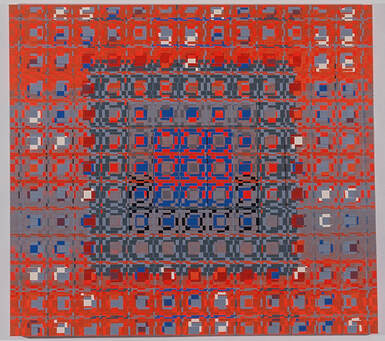

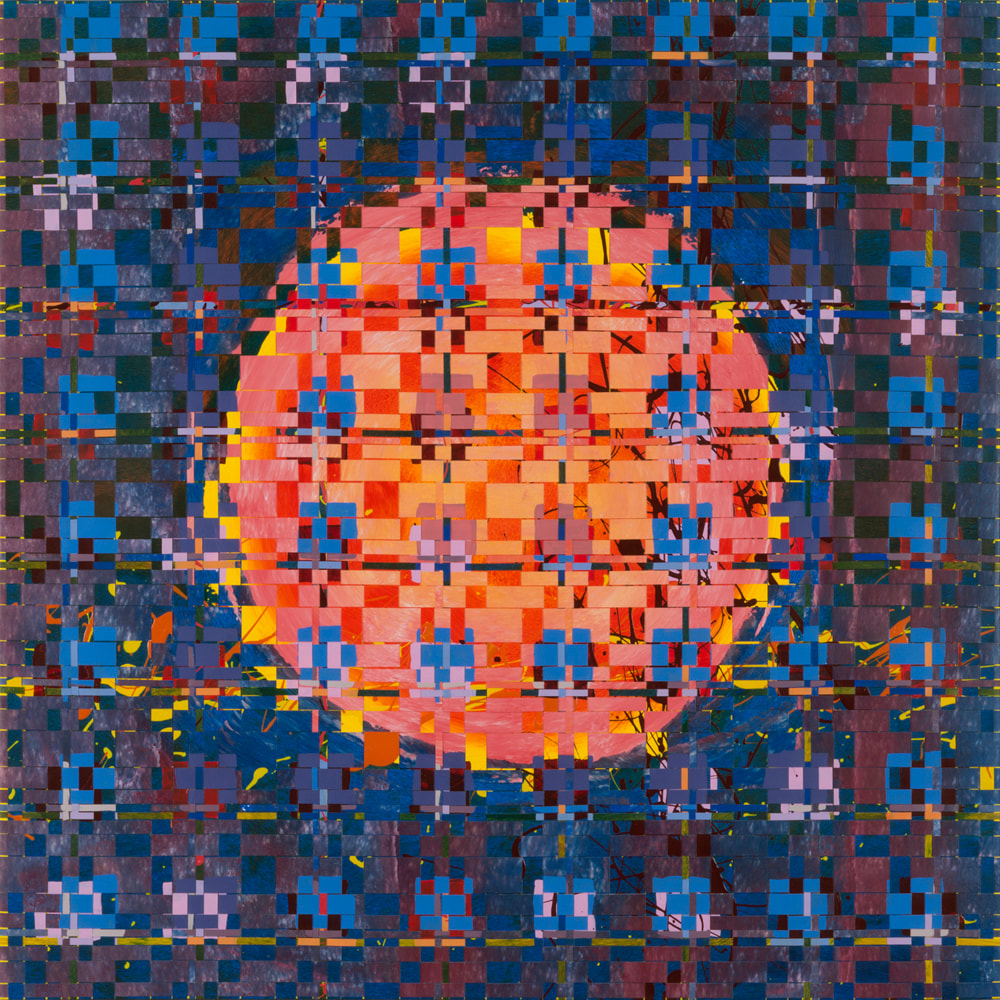

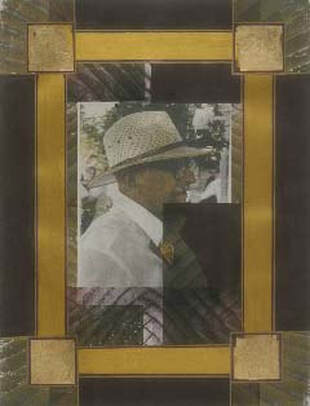

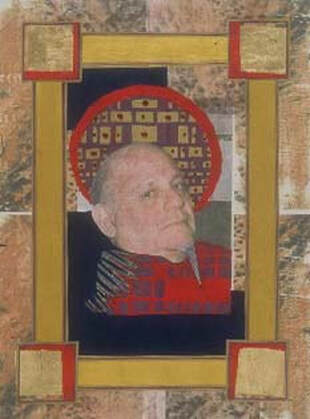

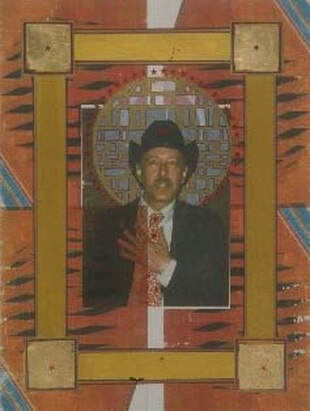

The last installment of HeartWood—the story of a young writer’s devotion to his grandmother and her literary legacy—got me thinking about other stories of art and devotion, which took me back to a trip to Albuquerque three years ago.  Mosaic in Albuquerque's Old Town Mosaic in Albuquerque's Old Town Albuquerque, nearby Santa Fe, and their surroundings are spilling over with creative people whose devotion to their art is evident. Painters, sculptors, mosaic artists, multi-media creators, jewelry designers—they're everywhere, and so are the fruits of their talents.  Promoting the Santero Market Promoting the Santero Market Evident, too, are signs of a different kind of devotion: works of art inspired by spirituality and religious faith. I learned about one type of this art from two women I chanced to meet on a Sunday morning in Albuquerque's Old Town. Felis Armijo and Ramona Garcia-Lovato were sitting at a table in front of San Felipe de Neri Church, signing up volunteers to help with the upcoming Santero Market. Santeros (and santeras) are artisans who craft religious icons called santos. Originally created for churches, these statuettes of saints, angels, Mary and Jesus, usually carved from wood and often decorated with home-made pigments, are now sold to tourists.  My conversation with Felis and Ramona rambled from topic to topic, touching not only on art, but also on writing, life stories, geography, and human nature. From their curiosity and warmth, it was clear these two women were dedicated not just to the event they were promoting and the parish to which they belonged, but also to connecting with other people—an art in itself.  Petroglyph Petroglyph After our time in Old Town, Ray and I ventured out to Petroglyph National Monument, a short drive away. One of the largest petroglyph sites in North America, the monument features designs and symbols carved onto the surfaces of volcanic rocks by indigenous people and Spanish settlers 400 to 700 years ago. The site and its images still hold spiritual significance for the descendants of both groups of people.  Significant symbols Significant symbols The meanings of some symbols have been lost over the centuries; others are known by a few indigenous groups, but it is considered culturally insensitive to reveal the meaning of an image to others. For me, it's enough to know that the symbols meant something to the people who created them and to ponder the combination of location and inspiration that gave rise to their work.  Larry Schulte Larry Schulte Not all works of devotion have religious significance. They also can be inspired by a more secular kind of admiration. Case in point: my friend Larry Schulte, an artist who now lives in Albuquerque, created his own "Saints" series, featuring mortals who have made a difference in his life. “I was raised in a fairly strict Roman Catholic home, and I left that faith many years ago—mostly because of their stance on gay people, that we were sinful,” Larry reflects. “These saints in some way replace the saints I learned about in my childhood . . . They are all loving, sharing people who have made my world a better place. We all need something to believe in. For me it is love, art/creating, and people, rather than any organized religion.”  St. Lou St. Lou Some of the fifteen mixed media pieces, which Larry created at the Ragdale Foundation, an artist's colony north of Chicago, feature well-known figures—such as the innovative composer Lou Harrison and Harrison's life partner Bill Colvig, an instrument builder who collaborated with Harrison on gamelans and other percussion instruments. But they also include more personal choices: Larry’s undergraduate art instructors, St. Jack and St. Keith, for instance. “Jack was particularly influential in my pursuing art,” Larry recalls.  St. Elvira St. Elvira St. Elvira’s son Peter was Larry’s roommate and best friend during their days at the University of Kansas in the late 1970s to early 1980s. Elvira lived in New Jersey but had visited Peter and Larry in Kansas. “After I moved to New York City, she included me in holiday family gatherings when I wasn't able to get back to my own family in Nebraska. She adopted me as another son.”  St. Bill St. Bill In 2016, Larry and his partner Alan Zimmerman, a percussionist, traveled to San Francisco for a concert of Harrison's music to celebrate what would have been his 100th birthday. Two of Larry's art works (St. Lou and St. Bill) were exhibited at the concert, which was sponsored by the non-profit organization Other Minds.

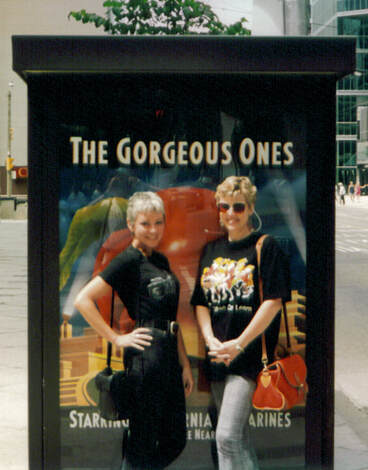

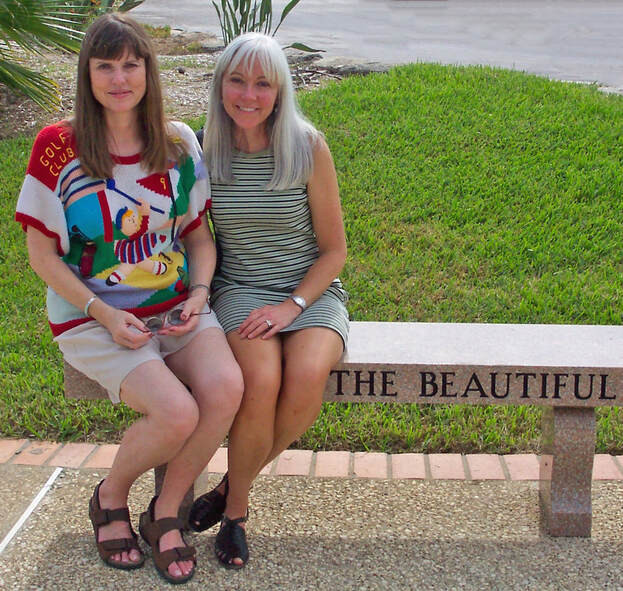

If April is the cruelest month, as T.S. Eliot contended, then July must be the friendliest. At least ten countries celebrate Friendship Day in July: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, Nepal, Pakistan, Spain, Uruguay, and Venezuela. What better time, then, to commemorate a 33-year testament to an even longer friendship?  The way we were -- as thirty-somethings The way we were -- as thirty-somethings This particular tradition began in 1987, when I bought a blank book and wrote an entry in it for my friend Cindi’s birthday, promising to add another entry every year. With the exception of a few years that I somehow let slide by, I’ve kept my word, documenting the ups and downs of our lives—often eerily parallel—and our passage from thirty-somethings to senior citizens.  Lining up for high school commencement Lining up for high school commencement Our friendship goes back even further. My first recollections of Cindi are from fifth grade, when we were in different classes but sometimes hung out together on the playground. We got to know each other better in junior high and were best of friends by high school, when we spent countless hours cruising the Sonic together. When I moved away to Samoa, Cindi saved my letters, which proved invaluable in writing my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta. In college, we were protest and peace-march buddies.  Younger days Younger days Then we moved to different parts of the country: Cindi to Texas, me to California, then Kansas and Michigan. Yet we never lost touch, continuing to exchange letters and phone calls, then transitioning to email, and visiting each other when we could. In time, our interests and political leanings diverged. Quite a bit. I wouldn’t say we’re on opposite ends of the spectrum now—we still agree on many issues—but we do have distinct differences. Once that became apparent, though, we made a conscious decision not to let those differences undermine our friendship.  1994 meet-up in Toronto, where we started the tradition of trying to find backdrops that attested to our (real or imagined) gorgeousness 1994 meet-up in Toronto, where we started the tradition of trying to find backdrops that attested to our (real or imagined) gorgeousness Fortunately, one thing we’ll always have in common is our offbeat sense of humor. That, and the birthday book—along with cards, calls, and emails—continue to cement our bond. Every year, Cindi mails the book back to me, and every year I write my entry—sometimes adding a photo of the two of us together, if we’ve managed a rendezvous that year—before mailing the book back. After all these years, the cloth cover, decorated with pressed flowers, has begun to fray. I guess that’s to be expected. We’re not quite as fresh as we were thirty-three years ago, either (though we like the think we are).  A decade later, in another "beautiful" setting. Corpus Christi, Texas, 2004 A decade later, in another "beautiful" setting. Corpus Christi, Texas, 2004 As memories have filled the book, and it’s become more precious to both of us, we’ve wondered if mailing it back and forth might be too risky, if maybe I should find a different way of adding entries. That thought crossed my mind this year as I put the book in the mail a few weeks ago, intending for it to reach Cindi in plenty of time for her June birthday. And then—oh, no—it happened. Due to a post office snafu so byzantine it would take another whole blog post to detail, the book was lost in the mail. Not only did it not arrive in time for Cindi’s birthday, it went missing without tracking information, so there was no way of finding out where it had gone. We consoled ourselves with the knowledge we’d both made photocopies of the pages. Cindi wasn’t sure where she’d put hers, but I was pretty sure I’d made a copy just last year and put it in a file under her name. Sure enough, I found the copy in the file, only to discover I hadn’t made it last year, I’d made it nine years ago. Now, as we wait for the book to show up—and we have to believe it will show up—I look back at pictures from all those years and re-read the entries I managed to save and know that, book or no book, we’ll always have something worth celebrating.

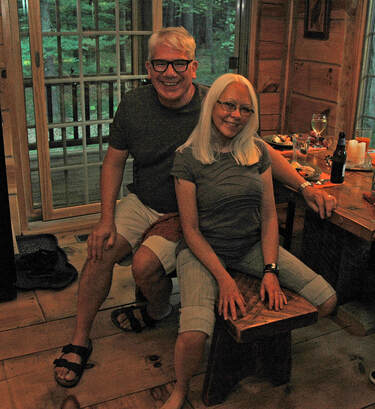

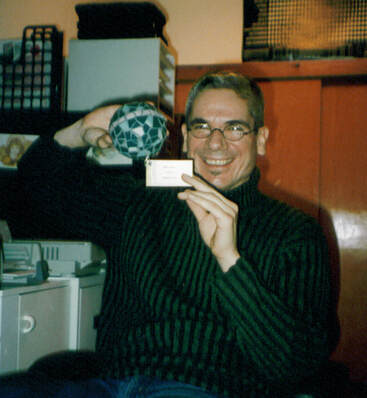

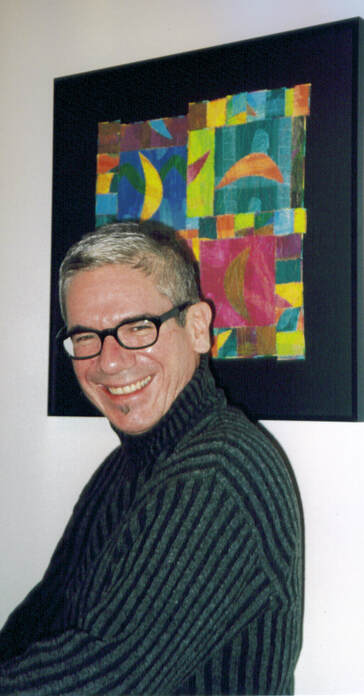

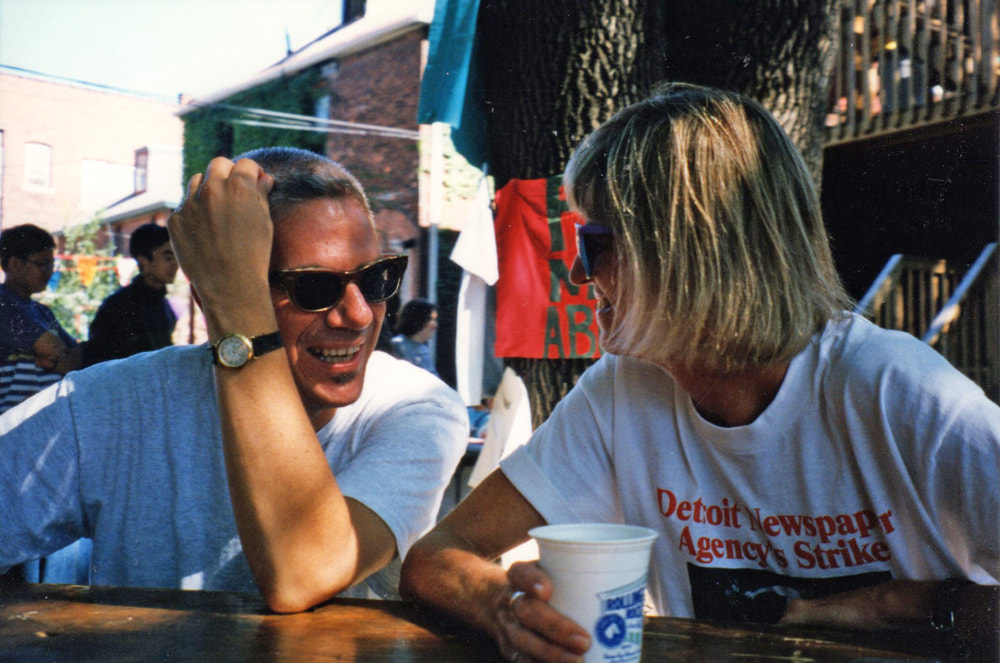

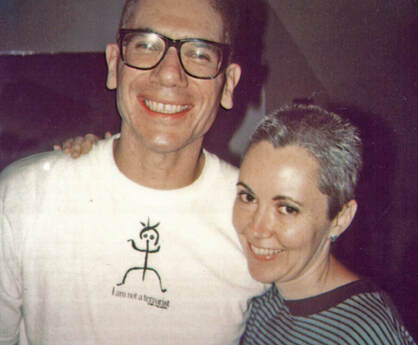

I know it’s not the week for my regularly-scheduled blog post, but I’m offering this special edition as a tribute to very special person. Reeling with grief when my dear friend John Tanasychuk died last week, I posted photos of him on Facebook, along with obituaries that were published in Florida and Detroit newspapers. Doing those things—and reading the comments from friends who were kind enough to take a moment to reflect on John’s life, whether or not they’d known him—was a comfort. But there’s so much more I want to say and share about John, and HeartWood seems the right place to do that. After all, this blog was his idea.  The idea for HeartWood came out of this visit The idea for HeartWood came out of this visit It all started when he and his husband Steve visited Ray and me here in Newaygo about five years ago. Over lunch at Hit the Road Joe Coffee Café, I groused to John about how authors and would-be authors nowadays can’t just write books, they have to create “platforms” to make themselves visible to publishing professionals and potential readers. “I guess I’ll have to start a blog,” I whined. “Everything I read says to do that. But I have no idea what to blog about.”  John appreciated creative projects, like this mosaic ornament I made him one Christmas John appreciated creative projects, like this mosaic ornament I made him one Christmas John, in his characteristic upbeat manner, refused to buy into my glum attitude. “You’d be great at it,” he insisted. “And I bet you’d love doing it. Just write about your life here—all the interesting and creative people you know, the places you go, the things you do.” Hmmm. He had a point. I thought it over, came up with the theme of “creativity, connection, and contentment,” and began to get excited about the idea. And so HeartWood was born, with John as one of its most loyal readers and cheerleaders. That’s the kind of friend he showed himself to be all through our thirty-plus-year friendship. We first met in 1985, when John was a reporter for the Windsor Star and I was the science writer for the Detroit Free Press. We were both covering a geography convention at the Renaissance Center and happened to sit next to each other at a press conference. I told him I found it hilarious that a group of geographers needed maps to find their way around the Ren Cen’s maze-like passages. He saw the humor, too, and laughed his delighted, almost childlike laugh. We traded business cards, and instead of throwing his into a drawer as I did most cards I collected, I put it in my Rolodex, hoping our paths would cross again.  Young John in early Free Press days. Even work was fun with John in the desk next to mine. Young John in early Free Press days. Even work was fun with John in the desk next to mine. That didn’t happen until three years later, when he showed up in the desk next to mine at the Free Press, having just been hired as the food writer. I knew I was going to enjoy being desk-mates when the first thing he did was tack a picture of Liberace on his bulletin board. Before long, we were sharing laughs and confidences, so easy to do with John. Both fans of the Canadian comedy group The Kids in the Hall, we could crack each other up with a line or a gesture from one of their routines. He also liked to tease me about being such a compulsive neatnik about my work space. Many times I would return from a bathroom break to find mail strewn across my desk. It looked like an accident, but eventually I realized it was John’s deliberate work—a trick to see how long it would take me to straighten things up and put everything back in its rightful place. (Answer: About one nanosecond.)  John could be supremely silly . . . or serious John could be supremely silly . . . or serious John did silliness better than anyone I know, absolutely unselfconsciously, but he did serious just as well. He had a gift for putting people at ease and giving his full attention to every conversation—never distracted, always fully present. And curious! Which made his visits to my house interesting. Not only was he constantly asking questions, some of them most unexpected and fascinating to consider, but he also had no qualms about opening cupboards to see what was inside or poking through my closet, bureau drawers, and file cabinets. If anyone else had done that I might have thought it nosy. But when John did it, it was just part of the who-knows-what’s-next fun of having him around. Cooking for John was part of the fun, too. He knew and loved food and cooking, but he wasn’t a snob about it. He appreciated everything I made, from the simplest bean salad to the most elaborate . . . huh, now that I think about it, I don’t recall ever making anything elaborate for John. He was so easily pleased with simple fare, why get fancy? Before one of my moves, I cleaned out a huge accordion file of recipes I’d collected throughout my life, including some I’d inherited from my mother decades earlier. Jell-O molds, casseroles, layer cakes, Christmas candies, that sort of thing. I mentioned the project to John—who by this time had moved with Steve to Florida—and said I hated to throw all those recipes away but couldn’t imagine anyone would want them. “Send them to me!” he said. So I stuffed them into the biggest mailing envelope I could find and sent them off. Soon after, he called, having gone through a good number of them, wanting to hear stories about the dinner parties where my mother served some of the dishes and curious (always!) why I had so many recipes for roast chicken and anything containing bananas, figs, or eggplant. While both at the Free Press, we got in the habit of taking lunch-hour walks together. Sometimes it was to actually go to lunch—usually somewhere like Ham Heaven for bean soup—but usually it was just to run errands and talk about anything that came to mind or resulted from John’s incessant questioning. Over the course of our friendship, we saw each other through staggering losses: the death of my husband Brian in 1989 and five years to the day after Brian’s passing, the death of John’s partner Joel. We designated October 15, the anniversary date, as “Widows Day” and made sure to check in with each other on that date every year. So often were John and I seen together at the credit union and in shops and cafés, the tellers, clerks, and servers thought we were a couple. We found that assumption terribly funny, since John was gay and I, recently widowed and recuperating from cancer treatment, was about as interested in a romantic relationship as I was in flying to the moon. Which is to say not at all (unless John had been going to the moon, in which case I might have considered it). Eventually, though, new romance came to both of us, and we both reacted as good friends do, thoroughly checking out the other’s suitor. The first time Ray picked me up at work for a date, John and another dear friend, Emily, stationed themselves in front of the Free Press building, pretending to take a smoke break, but really scrutinizing the shady-looking guy in the black truck. And when John took up with Steve, I was perhaps a bit more discreet, but still did due diligence to be sure Steve’s intentions were honorable. John and Steve’s wedding in 2014 was one of the most joyful marriage ceremonies I’ve ever had the pleasure of attending. And one of the most interesting, blending John’s Ukranian and First Nation Anishinaabe ancestry and Steve’s Jewish heritage. When John was diagnosed with lung cancer four years ago, I was heartbroken at the thought of illness stealing his energy and élan. Yet I had a feeling John would handle cancer as he handled everything, with grace and even good humor. He did. When he came to my book launch last fall, he was as vital and full of fun as ever. He didn’t just attend, he participated, helping out at the signing table, chatting up guests, and charming everyone he met. I have a feeling that wherever John is now—and I want to believe he’s still somewhere—that’s exactly what he’s doing. And in these uncertain times, instead of giving in to sadness and worry, I’m doing my best to channel a bit of John’s bright spirit. Be sure to come back next week for part 2 of the HeartWood Author Expo.

Santa, suited-up Santa, suited-up Santa came to our house early this year. Though he arrived in an SUV, not a sleigh, and he wasn’t “dressed all in fur from his head to his foot,” his long beard and the twinkle in his eye gave him away. Truth be told, a visit from this Santa was high on my Christmas wish list. I’d often seen him around town and wanted to know how he ended up in Newaygo instead of at the North Pole. Turns out he grew up right here in Newaygo County and after a couple of decades away, returned to make this his home. While he admits to owning a few red suits, and he’s been seen in the company of reindeer, this Santa, who calls himself “Charlie Johnson,” doesn’t claim to be the real Santa. Then again, he doesn’t claim not to be. He told me the same thing he tells children who press him on the question.  Sure looks like the real one to me Sure looks like the real one to me “Santa can’t see billions of kids all at once, at every mall, so he has helpers that help him out. It’s up to you to decide which one is the real one.” There are so many of these surrogate Santas, in fact, they’ve formed a brotherhood, mingling (and jingling, no doubt) with one another at Santa schools and Santa conventions. Every October, Santa Charlie heads to the Charles W. Howard Santa School in Midland. There, some 300 Santas, Mrs. Clauses, and elves brush up on everything from the history of Saint Nicholas and Santa Claus to proper dress, reindeer habits, radio and television interview tips, and other useful tidbits. Most of all, “it’s about the spirit of being a Santa,” says Charlie. Of course, cookies are served, along with pointers on the do’s and don’ts of Santa-ing. The number one no-no: don’t promise to grant a wish or bring a particular gift.  I know one little girl who always appreciated a low-key Santa. She's not too sure about this one. I know one little girl who always appreciated a low-key Santa. She's not too sure about this one. Santa Charlie has a few of his own rules of thumb, as well. “I’m more of a low-key Santa,” he says. “I think the kids respond to that better, especially the littlest ones. I won’t force them to sit on my lap. If the parents try and put them onto my lap, I’ll say, ‘No, hold them, or see if they’ll stand beside me.’” In a venue where Santa can move around a bit—on the Santa Train that runs between Coopersville and Marne, for instance—Charlie resorts to stealth. “I’ll sneak up behind them while their parents are holding them and do a photo bomb so the parents can get their picture of the kid with Santa.” He laughs—more of a chuckle than a ho-ho-ho—and another voice pipes up from the corner: “Santa is the most-photographed icon in the world.” That’s Mrs. Claus, AKA Carol Nickles, who came along with Santa Charlie on his visit to our house. The couple met at Santa school three years ago and became an item about a year later. Now they’re “having a blast” making the Santa scene together, says Carol. At a recent Santa convention they performed in the talent show, harmonizing on a swing tune called “Holiday Romance” while accompanied by a Mrs. Claus from West Virginia. Carol, a seamstress, wore a glitzy red ball gown she’d created, and Charlie was gussied up, too. “So fun, so fun,” Carol recalls. Also fun: Appearances at the Rooftop Landing Reindeer Farm in Clare and field trips with busloads of other Santas and Mrs. Clauses from the Midland Santa school to the steam train in Owosso and Bronner’s Christmas Wonderland in Frankenmuth. “Can you imagine these big coach buses pulling up to Bronner’s and all of us getting out?” says Carol. “Now, we’re not dressed in Santa garb, but there are all the beards, and we’re wearing red and green.”  Charlie caroling at the Christmas Walk Charlie caroling at the Christmas Walk Santa-ing isn’t confined to the Christmas season anymore. “Christmas in July is starting to be thing,” says Carol. She and Charlie were invited to add their festive flair to the Star 105.7 radio booth at one such event. Charlie agreed on the condition that he wouldn’t have to wear his full Santa suit in 85-degree weather. Instead, he came up with a “Santa casual” ensemble of red shorts, a Santa-print Hawaiian shirt, and a straw hat, and Carol lightened up her Mrs. Claus-wear accordingly. “Most people would say being a Santa is a calling,” says Carol. Charlie agrees, though Santa-ing doesn’t consume his whole life. He’s plenty busy with a variety of other activities, even after his recent retirement from TrueNorth, where he ran the LifeLink program and coordinated the Newaygo County Senior and Caregiver Expo. He’s often seen playing harmonica at River Stop Café’s open mic nights and running the sound board for Lion Heart Community Theater productions and concerts at Dogwood Center for the Performing Arts. This time of year, you’ll also find him caroling with the men’s chorus that strolls through Newaygo during the yearly Christmas Walk. Alas, our house has no chimney, so I couldn’t put Santa Charlie to the test of exiting the traditional way. He just walked out the front door like anyone else. But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight . . . Oh, who am I kidding? His windows were rolled up; I didn’t hear anything. I’m pretty sure, though, that as he drove away, he wished us “Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night.” What are your favorite Santa memories?

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed