|

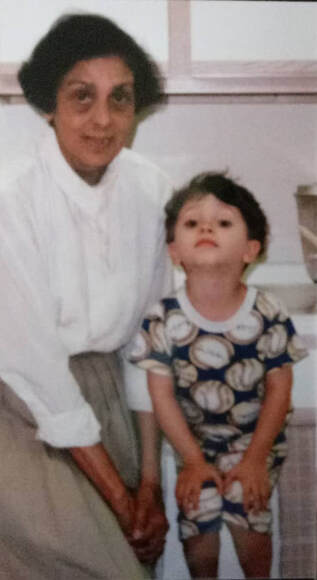

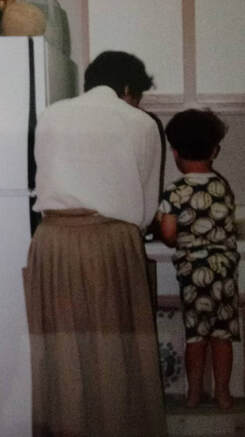

With in-personal author events still on hold indefinitely, I've decided to devote one blog post each month to an author interview. I'm kicking off this new feature today with a Q&A that tells the remarkable story of a young writer's devotion to his grandmother and her literary legacy. For reasons you'll understand as you read on, it wasn't possible to interview Barbara Mahase Rodman, author of the recently published novel Olas Grandes. Instead, this interview is with her grandson David Kuhnlein, who edited and published the book after the long lost manuscript was unearthed. The manuscript for Olas Grandes was stashed in a trunk for about forty years before you found it. Tell us more about how you learned of its existence and managed to locate it. For the most part that’s true: the manuscript sat in her trunk since 1979, full of potential, charging up like a battery. Barbara Mahase Rodman (my grandmother, known by her grandsons as Babbie) got many rejection letters in the 70s and 80s, due to a couple factors, one of which was her animosity towards the editing process. Another was her interest in larger publishing companies. I hadn’t heard of Olas Grandes, or at least I’d forgotten about it, until I read my great grandmother’s autobiography My Mother’s Daughter – a testament to growing up as a strong Indian woman in Trinidad. My mom told me that I was mentioned in the back of the book where Anna Mahase Snr. wrote about the family. So, of course, that’s the first place I looked! Sure enough I found mention of me, but more rewarding was a typo – it said that Babbie had published two books: Love Stories for All Centuries, which I had read, and Olas Grandes. My mom, uncle, and I quickly searched Bab’s house for the manuscript, and hidden in a massive wooden trunk, brimming with so much of her writing, we found it. Did you know right away you wanted to edit and publish the novel? What led to that decision? Well, first I wanted to read it. There’s something incredible about reading a book written by an elder like Babbie who, at the time I found the book, suffered greatly from dementia. The manuscript's weight in my bag became a talisman, and as I walked around with it I felt like I was hanging out with her, aeons ago, in Trinidad. After reading the first few chapters I took a train across the country. I didn’t want to take the only copy of the book on the trip, so I let those early chapters linger in me. I talked to my friends Adam and Katie a lot about the project. Even speaking of the project excited me, and it was in the tangle of conversations -- and questions I asked every reader and writer I encountered -- that I decided something had to be done with this book. At the time, I was writing a series of lyric essays on illness and a recent surgery I’d had. But while writing them felt important, it also made me physically sick. Focusing my energy on transcribing Olas Grandes was a way to keep writing, while also taking a needed break from my own project. Gail Kuhnlein, my mom and Barbara's daughter, is also a writer, and lucky for me she agreed to help edit the book. I couldn't have done it without her. What was Barbara’s reaction when you told her of your intentions? How old was she at that point? Was she able to be involved in the process as you worked on it?  Barbara and David, August 2019, three months before Barbara's passing Barbara and David, August 2019, three months before Barbara's passing Honestly, her reactions depended on the day. In the two years before Barbara passed away, my visits to her house increased, and I began to help informally caretake. Because of her memory, we had certain conversations regarding Olas Grandes over and over again, to the point where I observed patterns and ways to create shortcuts around them. For instance, sometimes she’d tell me that Olas Grandes was not a novel, but a story, and it was already published. So I’d have to preface a conversation about her book by showing her the physical manuscript and explaining that it’s different than her other book. But other times, like magic, she knew exactly what was happening and was thrilled. “Never could I have imagined,” she once told me, “that this darling, darling little boy would be helping me publish my book.” She was 90 when I re-discovered Olas Grandes, and the project took roughly two years to manifest. She was involved peripherally. I would read passages to her that I didn’t understand, either because of her diction or place names, and asked her to explain. Cultural words, fauna, flora, and Trinidadian myths stayed with her, and she usually had no problem giving me details or stories associated with these passages. In the acknowledgments, you say you tried to keep Barbara’s voice intact during the editing process. Being a writer yourself, was that difficult? Did you ever find yourself wanting to impose your own style? It was easier than I thought it’d be. I have a knack for imitating other writers, and have a lot of fun impersonating. I think of it like a painter trying to paint . . . oh anyone, to use a Trinidadian example, M.P. Alladin, by sight. (A more accessible example perhaps is how musicians “cover” other songs, which is not a rip off, but a compliment, a head nod, perhaps even an advertisement.) It’s a fantastic exercise to let go of the ego that writers so often cling to around their work, and this release opens up a unique freedom to explore the architecture of language from a new vantage point. Also, I hadn’t written much fiction yet (that’s changed significantly since then), so perhaps I had a leg up there. The setting in Trinidad plays such a big part in Olas Grandes. What did that place mean to Barbara? Do you know how she came to write Olas Grandes?  Young Barbara at McGill University Young Barbara at McGill University At heart she’s an island girl fortified with the blood of a princess. She was born and raised in Trinidad, where her grandmother Rookubai (a princess escaping an arranged marriage) arrived around 1887, a stowaway on a ship from India. I mention India because many Indians held onto Hindu traditions – celebrating Diwali and the belief in reincarnation – even though Canadian missionaries attempted to convert all the Indians on the island to Christianity. Although Hindu themes are peripheral in Olas Grandes, I think that Barbara’s interest not only in Hindu customs, but also her interest and study in the occult, was nurtured by island life. She called the Caribbean “the perfect background for dreaming.” One of my persistent, and unanswered questions I posed to Barbara, was: who is the character Ma Becky based on? Many of her characters are fictionalizations of family members, usually adorned with pieces of herself. Ma Becky is the only character I could never see clearly with this template. Bab knew some Trinidadian witches when she was growing up, who lived on the beach, but part of me thinks that there’s quite a bit of herself in Ma Becky. Babbie always loved fairy tales, fables, and myths, partly because of their appeal to both children and adults. She stayed rooted to the Caribbean landscape because it’s where she spent her youth. She had also recently and tragically lost her son, David Rodman, in 1977, just a couple years before writing Olas Grandes. I think that writing the book was a way for her to enter an alternate reality, in which Davey was a young boy again, and she was living in an idyllic gothic romance in her home country, but that’s just a guess. Did working on Barbara’s novel give you any new insights into her life?

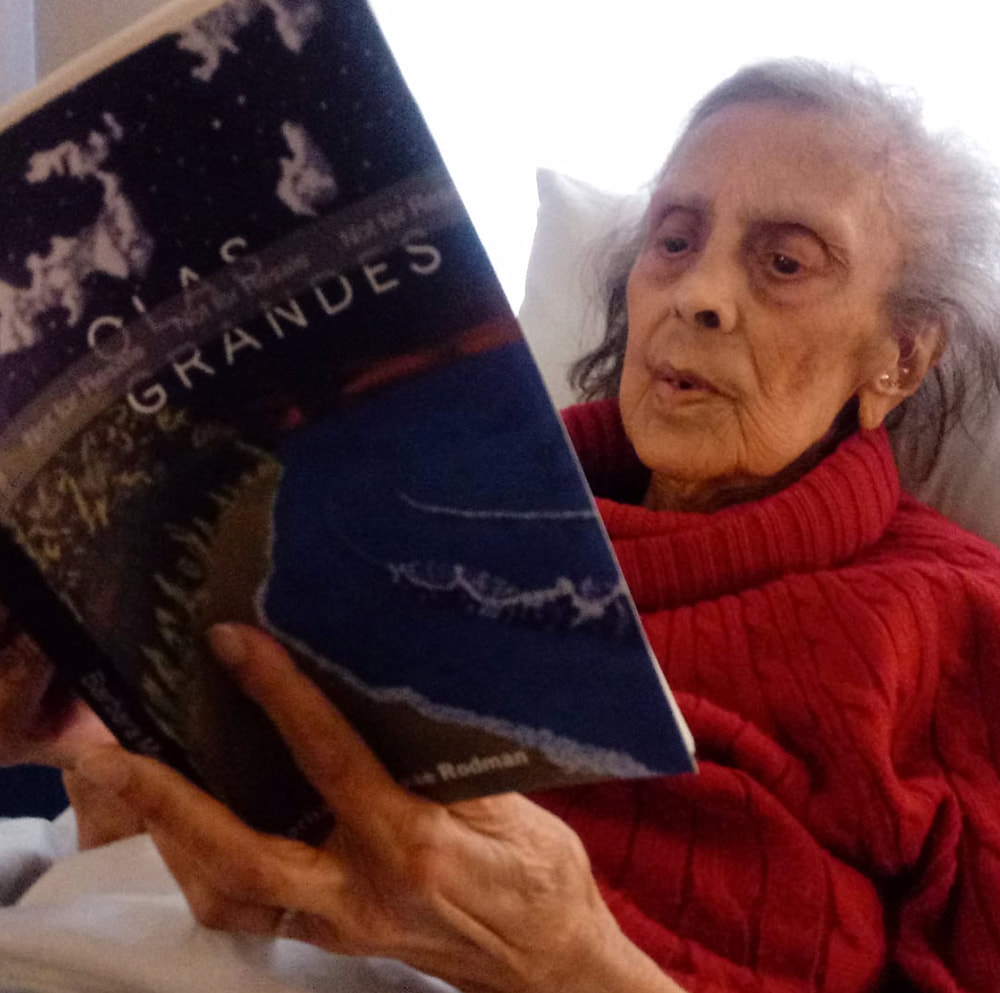

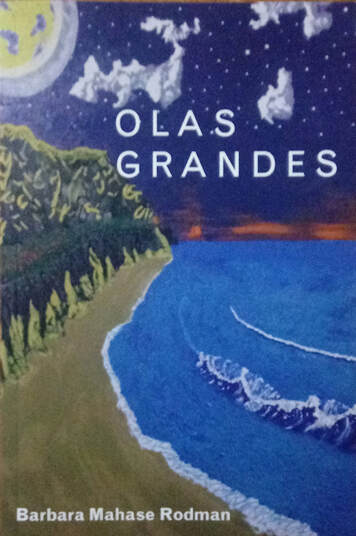

Barbara was able to see the book in print before the end of her life, wasn’t she? What was that like – for her and for you?  Barbara holds a review copy of her novel Barbara holds a review copy of her novel The review copy for her book arrived twelve days before she died. The same night we got the first full box of Olas Grandes copies was the night she passed away. Seeing her hold the book and flip through it was an incredible moment of this journey. With people still reading and buying and reviewing her book, that journey continues. Between my mom and me, we read Babbie about seven chapters before she died. She didn’t remember writing the book, but at the end of each chapter she'd say, “I like this story, keep reading.” Usually when I'd read her the Detroit News she’d get burnt out listening about half-way through an article. Not so with Olas Grandes. I can only imagine what went on in her mind, listening to her grandson and daughter read words to her that she wrote some forty years ago. There was some magic there for all of us. Your uncle Ken created the stunning cover art. Was the cover design a collaborative process, or did you give him carte blanche?  The book cover The book cover My uncle Ken and I sat at the kitchen table for hours, discussing the project. When we decided that we were going to independently publish the book for temporal reasons, as well as “sweet romance” not being as salable as some of the more hardcore stuff in the romance marketplace, we decided that he’d paint the cover. I gave him some ideas, and we read some passages from the book aloud to give us a sense of voice and place. But Ken was born in Sangre Grande, so he knew what the coastline looks like better than I do! One funny thing about the painting was that he started painting these tiny waves, but since olas grandes translates to “big waves”, my mom suggested making the breakers a little bigger. It was a Homer Simpson moment, I think he even smacked his forehead, “D’oh!”. Barbara’s bio says she also wrote Love Stories for All Centuries. Can you say more about that? She also contributed to the Detroit News Sunday magazine. What kinds of thing did she write for the magazine?  The cover of Barbara's first book The cover of Barbara's first book Love Stories is a magical little book weaving together love stories across three continents, the common thread plucked from a dreamlike vapor, the mist of eternity on which every story’s loomed. It’s her first book, published in 1985 by the International University Press and printed in an underground style. I’m biased but I think it’s an exceptional project. She mingles famous love stories with her own; lovers meet in and out of dream worlds, recognizing one another by their eyes, and it’s all built on the history of Trinidad, India, and Spain – her spiritual home. Babbie would say to me, “I don’t believe in reincarnation. It’s not something I have to believe in because I know that I’ve lived another life in Spain.” Reading her books and articles in the Detroit Sunday News Magazine, which used to come folded inside the Sunday edition of the Detroit News, it’s clear that for Barbara, death was not a barrier but a reprieve. She concludes one of her many articles by writing, “I am a dreamer living in my own world of dreams. I hate reality, but Life is reality, therefore I compromise and leave my dreams alone for a while, as long as Life lasts. After Life, I can have my dreams and all the things I love all to myself.” She wrote emotional pieces, like this one, but she also contributed silly articles. In one of my favorites, she talks about each item from “Twelve Days of Christmas” – partridge, pear tree, drummers, rings, etc. – and adds up their price, telling the beloved what to do with her gifts. Which ones to keep, which to donate to a local bird sanctuary (there are a lot of birds) and what she should now think of her “true love” after he heaps these excessive gifts into her lap. “I don’t know about you,” she writes, “but I’d be happy with a single gold ring.” I see from the Olas Grandes Facebook page that you’ve been matching proceeds from sales and donating to worthy causes. What went into your decision to do that, and how’s it going? This entire project revolves around a sense of duty. Not only to my grandmother, or our family, although that’s a large part of it, but there was also something more elusive, and larger. I have a few practices I perform religiously. One is writing. Another is listening. Longstanding systemic health and social inequities disproportionately affect Black people in the US – and the coronavirus pandemic is highlighting that fact. It’s important to know where our money’s going. The decision to donate to Detroit Will Breathe is just one way to support the amazing anti-racist work being done right now, as people continue to march, and people continue to buy. Do you have any other writing or editing projects in the works? I just finished my first novella – it’s a work of literary fiction about the notorious Austro-Hungarian vampire Béla Kiss. I’m still waiting to hear back from a few of my favorite small presses. I’m also continuing to write flash fiction, film reviews, and poems. Much of my own recent writing is forthcoming or published in online lit journals, and easily found if interested. (davidkuhnlein.wordpress.com) Also, sitting in my “to-do” pile are three more of Babbie’s full length manuscripts, two of which I’ve read, and are fantastic. I’m not promising anything, but if they get transcribed and edited, I’ll update the Olas Grandes fans on our Instagram, which I’m most active on @olasgrandesnovel. Anything else you’d like to add? I absolutely love your blog, Nan, and I’m so honored. Babbie would have been ecstatic. Thank you, from all of us, for the interview.

7 Comments

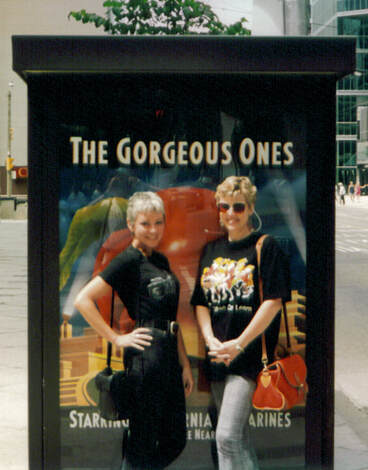

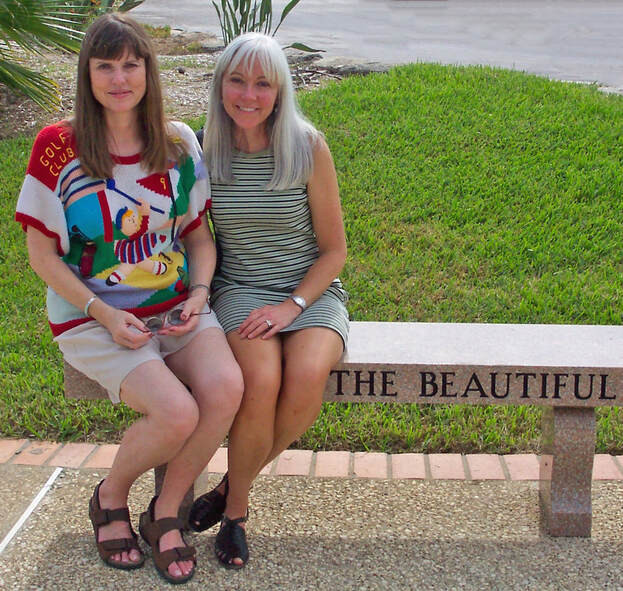

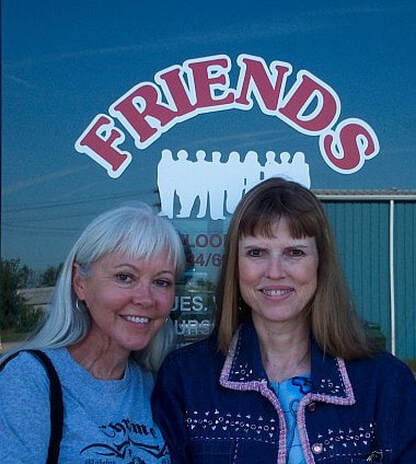

If April is the cruelest month, as T.S. Eliot contended, then July must be the friendliest. At least ten countries celebrate Friendship Day in July: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, Nepal, Pakistan, Spain, Uruguay, and Venezuela. What better time, then, to commemorate a 33-year testament to an even longer friendship?  The way we were -- as thirty-somethings The way we were -- as thirty-somethings This particular tradition began in 1987, when I bought a blank book and wrote an entry in it for my friend Cindi’s birthday, promising to add another entry every year. With the exception of a few years that I somehow let slide by, I’ve kept my word, documenting the ups and downs of our lives—often eerily parallel—and our passage from thirty-somethings to senior citizens.  Lining up for high school commencement Lining up for high school commencement Our friendship goes back even further. My first recollections of Cindi are from fifth grade, when we were in different classes but sometimes hung out together on the playground. We got to know each other better in junior high and were best of friends by high school, when we spent countless hours cruising the Sonic together. When I moved away to Samoa, Cindi saved my letters, which proved invaluable in writing my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta. In college, we were protest and peace-march buddies.  Younger days Younger days Then we moved to different parts of the country: Cindi to Texas, me to California, then Kansas and Michigan. Yet we never lost touch, continuing to exchange letters and phone calls, then transitioning to email, and visiting each other when we could. In time, our interests and political leanings diverged. Quite a bit. I wouldn’t say we’re on opposite ends of the spectrum now—we still agree on many issues—but we do have distinct differences. Once that became apparent, though, we made a conscious decision not to let those differences undermine our friendship.  1994 meet-up in Toronto, where we started the tradition of trying to find backdrops that attested to our (real or imagined) gorgeousness 1994 meet-up in Toronto, where we started the tradition of trying to find backdrops that attested to our (real or imagined) gorgeousness Fortunately, one thing we’ll always have in common is our offbeat sense of humor. That, and the birthday book—along with cards, calls, and emails—continue to cement our bond. Every year, Cindi mails the book back to me, and every year I write my entry—sometimes adding a photo of the two of us together, if we’ve managed a rendezvous that year—before mailing the book back. After all these years, the cloth cover, decorated with pressed flowers, has begun to fray. I guess that’s to be expected. We’re not quite as fresh as we were thirty-three years ago, either (though we like the think we are).  A decade later, in another "beautiful" setting. Corpus Christi, Texas, 2004 A decade later, in another "beautiful" setting. Corpus Christi, Texas, 2004 As memories have filled the book, and it’s become more precious to both of us, we’ve wondered if mailing it back and forth might be too risky, if maybe I should find a different way of adding entries. That thought crossed my mind this year as I put the book in the mail a few weeks ago, intending for it to reach Cindi in plenty of time for her June birthday. And then—oh, no—it happened. Due to a post office snafu so byzantine it would take another whole blog post to detail, the book was lost in the mail. Not only did it not arrive in time for Cindi’s birthday, it went missing without tracking information, so there was no way of finding out where it had gone. We consoled ourselves with the knowledge we’d both made photocopies of the pages. Cindi wasn’t sure where she’d put hers, but I was pretty sure I’d made a copy just last year and put it in a file under her name. Sure enough, I found the copy in the file, only to discover I hadn’t made it last year, I’d made it nine years ago. Now, as we wait for the book to show up—and we have to believe it will show up—I look back at pictures from all those years and re-read the entries I managed to save and know that, book or no book, we’ll always have something worth celebrating.

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed