|

On the last Wednesday of every month, I serve up a potpourri of advice, inspiration and other tidbits I've come across in recent weeks. In honor of National Poetry Month, celebrated every April, I'm sharing thoughts on poetry and language. And with this, a salute to my friend Cristina Trapani-Scott, whose poetry chapbook, The Persistence of a Bathing Suit is due out from Finishing Line Press next month. Plus this month's bonus: a preview of the fairy house Ray and I built for the second annual Enchanted Forest event at Camp Newaygo, coming up this weekend (April 29-30), and the story we co-wrote to go along with the house. Poetry comes nearer to vital truth than history. -- Plato The poet lights the light and fades away. But the light goes on and on. -- Emily Dickinson A poem is not simply words on a page but a way of touching the stars and having the stars that have fallen into the sea touch us. Our lives are poems. Everything arrives and passes away as it should, and we don't know the ending--which is the moment the entire poem, its meaning and music, is revealed--until the last line is written, even though it has perhaps existed in the eternal now all along. -- Sawnie Morris, in Poets & Writers magazine, November/December 2016 Poetry is just the evidence of life. If your life is burning well, poetry is just the ash. -- Leonard Cohen Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words. My language trembles with desire. -- Roland Barthes As a poet and writer, I deeply love and I deeply hate words. I love the infinite evidence and change and requirements and possibilities of language; every human use of words that is joyful, or honest, or new because experience is new . . . But, as a black poet and writer, I hate words that cancel my name and my history and the freedom of my future: I hate the words that condemn and refuse the language of my people in America. -- June Jordan Poetry is what in a poem makes you laugh, cry, prickle, be silent, makes your toe nails twinkle, makes you want to do this or that or nothing, makes you know that you are alone in the unknown world, that your bliss and suffering is forever shared and forever all your own. -- Dylan Thomas But words are things, and a small drop of ink, falling like dew, upon a thought, produces that which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think. -- Lord Byron Poetry is the language in which man explores his own amazement . . . says heaven and earth in one word . . . speaks of himself and his predicament as though for the first time. It has the virtue of being able to say twice as much as prose in half the time, and the drawback, if you do not give it your full attention, of seeming to say half as much in twice the time. -- Christopher Fry Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people. -- Adrian Mitchell All the fun's in how you say a thing. -- Robert Frost And now for something completely different . . . it's time to unveil our creation for this year's Enchanted Forest event at Camp Newaygo. Once again, the design is based on a story featuring Fairy Archie and his sidekick Hughie the Humongous Butterfly. It'll probably make more sense if you read the story first. (And if you missed last year's installment, you can read it here.) Be sure to come back next week for more fairy house pictures and a full report on the Enchanted Forest event.

8 Comments

Are you having a busy week? I'm not.  Full calendar, busy week? Not necessarily. Full calendar, busy week? Not necessarily. Oh, my calendar and to-do-list are plenty full, as usual: appointments, meetings, writing projects, household projects, pitching-in projects, activist activities, email and phone calls to catch up on, matters to check on (Where's my refund for those down mittens I returned last month? What's happened to the guy who's supposed to be re-staining our house? Why isn't insurance covering my upcoming dental work?). But I'm not going to say I'm busy. You know why? Because I have purged that word from my vocabulary, at least as it pertains to my own doings. The inspiration for this linguistic vanishing act came from an editorial I read in Mother Earth Living in early 2015.  Has "busy" become our default setting? Has "busy" become our default setting? "For many of us today, 'busy' isn't something we are from time to time when we're working on a big project. It's the state of our lives. It's our default setting," wrote the magazine's editor-in-chief, Jessica Kellner. "Being busy. . . validates our existence in an unsure world—if we're constantly busy, our lives must be important." But all that busy-busy-busyness can feel awfully frenzied and stressful, can't it? Don't you wish you could still do all the things you need and want to do, without feeling frantic?  Can you trick your brain into feeling less frenzied? Can you trick your brain into feeling less frenzied? Maybe you can. Maybe you just need to trick your brain, Kellner suggests. She cited a number of studies showing that simply changing one's mindset can have profound physical effects. For example, septuagenarians instructed in an experimental setting to live as if they were 22 years old sat taller, performed better on manual dexterity tasks and even looked more youthful after only five days of thinking young. Could a similar mental ploy help alleviate our sense of overload? Kellner thinks so. "Perhaps if we stop saying we're so busy, we'll stop feeling so busy," she concluded. "By aiming our thoughts toward serenity and calm, we might actually achieve serenity and calm—without changing anything about our daily schedules."  What a difference a word makes What a difference a word makes Intrigued, I started my own experiment, simply substituting the word "full" for "busy" when thinking and talking about my everyday activities. The change was subtle, but almost immediately I noticed a difference. "Busy" had felt like a burden. "Full" felt like a blessing. How fortunate I was to have so many interesting things to fill my days. And if they weren't all so interesting or rewarding, well, that's where another mind-shift could come in handy. This one I came across more recently in a blog post by Bella Mahaya Carter on She Writes, a website for women writers.  On paper or in our minds, we all have to-do lists On paper or in our minds, we all have to-do lists Carter shared her own to-do list from a recent day—a familiar-looking litany of pleasant enough activities (yoga class, edit memoir, write thank-you notes), along with a fair share of less-appealing tasks (clean kitchen, unpack from trip, grocery shop). Admitting she probably wouldn't get to everything on the list in one day, Carter wrote, "It helps to remind myself that it doesn't matter if it takes me two or three days to complete these items. What does matter is that everything on my list I'm doing for love." Everything? Really?  Is love really the answer? Is love really the answer? That's pretty much how Carter reacted when she first heard the love-centric notion, put forth by spiritual psychology pioneer H. Ronald Hulnick. When Hulnick told Carter's class at the University of Santa Monica, "The only reason to do anything is for love," Carter was skeptical, and immediately started thinking up exceptions.  Bella Mahaya Carter Bella Mahaya Carter But then she stopped herself and decided, as an experiment, to act as if it were true. Her to-do list didn't change much, but her approach to doing the things on that list did, and life felt lighter as a result.  A mind-shift lightens less-than pleasant chores A mind-shift lightens less-than pleasant chores "For example, instead of complaining about cleaning my house, I focused on how much I loved my family and my home, and how great it was that I was able to clean my home," Carter wrote. "It also occurred to me that I was lucky to have a home." The love filter also helps her choose new activities. When asked to do something she's not sure she wants to do, she asks herself: Where is the love here? "I root around and sniff out the love. If I don't catch its scent, I say no and move on." Though I'm having a little trouble finding the love in toilet cleaning (don't ask me to sniff that one out!), I'm trying to keep Carter's words in mind as I decide how to allocate my time each week. Now, let me ask you again: Are you having a busy week? Photo of Bella Mahaya Carter: http://www.bellamahayacarter.com/

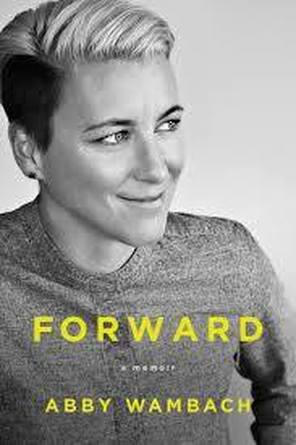

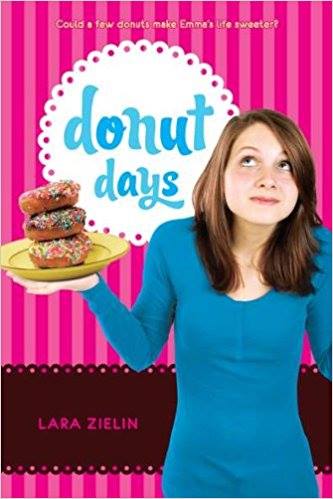

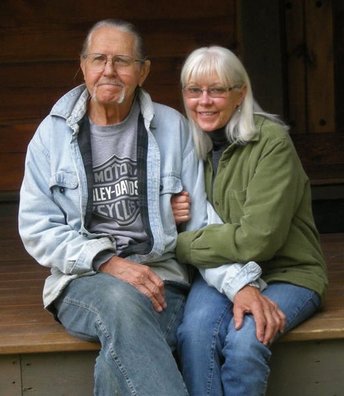

All other images are free-use stock images. Late last year, I was scrolling through Facebook posts when I came to one that stopped me short. Posted by my friend and former University of Michigan colleague Lara Zielin, it began: My last post of 2016 has taken me all year to write. I haven't wanted to admit this, but here's the truth. . . Lara went on to reveal that her thriving career as an author had withered. She had been in a slump for the past twelve months and had even questioned her own worth. My first reaction was sympathy. As a writer who's trying to become a published author, I know how difficult and tenuous the whole process can be, and how one's self-esteem rides up and down on successes and failures. My heart broke at the thought of sunny, upbeat Lara being knocked down. As I read on, my sympathy turned to admiration. Most of us use social media to trumpet successes and share happy occasions. How rare it is to read such a frank account of, as Lara put it, "humiliating failure." Lara's year-end post ended on an optimistic note, but rather than giving that away, I have asked Lara to tell you herself about facing failure and moving forward from there. Here's Lara:  Lara Zielin Lara Zielin Do you ever feel inexplicably drawn to read a particular book? This happened to me recently at Barnes & Noble, when I looked over at the new releases section and felt the mysterious pull to read FORWARD, a memoir by soccer player Abby Wambach. Mind you, I don’t like soccer. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a game in my life. And I had no clue who this woman was or why I should care about her story. But the tug toward the title wouldn’t relent, and I took it home.  The book that called to Lara The book that called to Lara Turns out, the universe was right. I wasn’t far into the book—12 pages to be exact—when this passage hit me over the head: I love [soccer] for what it gives me: praise, affection and, above all, attention. When I’m on the field I don’t have to plead to be noticed, either silently or aloud; it is a natural by-product of my talent. I loathe it for the same reason, terrified that soccer is the only worthwhile thing about me, that stripping it from my identity might make me disappear…Already I know I’m incapable of falling in love with the game itself—only with the validation that comes from mastering it, from bending it to my will. I read the words again and again, marveling that someone was brave enough to articulate what I felt, too. Only in my case it wasn’t soccer—it was writing. Or, I guess I should clarify and say writing novels. Writing books was the only thing I’d wanted to do since I was a little kid. I can remember the first story I wrote, when I was eight years old—not the text itself, but what the paper looked like, and what the pencil felt like in my hand. I’d write so much over the next decades that I would give myself a callus I still sport to this day, a permanent rough spot that has altered shape of my finger forever. It didn’t take long before the idea of what writing could do for me went hand-in-hand with the act of putting words to paper. This will be how I become famous, I would think. This is how I will leave my mark. This is how I will show people I matter. That I’m worth something. These ideas were pressing, even when I was very young. They were very deep, buried in a dark corner of my subconscious, and completely inextricable from the hard work of getting better at my craft and my determination to make a career out of books.  Lara's first novel, DONUT DAYS, hit the shelves in 2009 Lara's first novel, DONUT DAYS, hit the shelves in 2009 Fast-forward a few decades, to 2007 when I sold my first novel. It hit shelves in 2009. I was writing young-adult at the time, which was a perfect fit. I thought, this is it, and I kept going. My second book came out in 2011, followed by my third in 2012. I was under contract for a fourth book, which wasn’t coming as easily as the first three. It felt forced and uncertain. I wrote several versions, and each time my editor encouraged me to go back to the drawing board—to fix the characters, their motivations, the language…hell, all of it. To make matters worse, the books I did have out weren’t selling well at all. My shaky foundation of self-worth started to wobble. What if I wasn’t good at this? What if I wouldn’t or couldn’t become a writing success? Desperate to take a break from young adult, I started writing romance.  One of Lara's romances, published under the pen name Kim Amos One of Lara's romances, published under the pen name Kim Amos In 2014, I sold a trio of small-town romances at auction, giving me enough money to quit my full-time, big-girl job and take something part-time while I pursued this new venue. For a hot second, it was great. Until it wasn’t. These books didn’t sell well either, and when I pitched my publisher on a new series, they didn’t bite. They washed their hands of me and moved on. This caught me completely off guard. I figured my publisher would maybe low-ball me on the money but keep collaborating. After all, I was hardworking, I hit my deadlines, and the books I’d produced—while not bestsellers—had garnered great reviews and even an award nomination. This just wasn’t the case. And when my agent shopped my idea for the new series around to other romance publishers, no one would bite. My romance career had flamed out as spectacularly as it had started. In the meantime, the fourth book I’d written for my young-adult publisher was done, and I was enormously proud of it. After years of laboring over this story, I felt like I’d finally gotten it right. I thought, okay, romance is dead, but young-adult is still kicking, I can still be a success in this genre. Wrong.  Lara's writing buddy, Amos, reflects her discouragement Lara's writing buddy, Amos, reflects her discouragement My editor wasn’t a fan of the book at all—a historical middle-grade novel about a young girl who works at a logging camp for a winter in the Wisconsin Northwoods. I’d called it the book of my heart. I think if she could, my editor would have called it a hot mess. At this point, we all agreed it would probably be best if we parted ways. My young-adult publisher broke the contract with me, and any potential revenue streams I had through publishing—not to mention opportunities for the success I so badly craved—were gone. But Lara, you’re thinking, just write a new book! Just keep trying! And I would, I swear I would, if I had any ideas coming to me. But not only had my contracts dried up, my ideas had, too. Which brings me back to Abby Wambach and her memoir. When she couldn’t play soccer any more—she had essentially aged out, and her body was fighting her with injury after injury—she fell apart. And I guess I did too when I couldn’t write novels anymore. I gained weight. I didn’t feel much like going out. I kept asking my husband, “What do I do? Writing novels is the only thing I’ve ever wanted.”  Lara shot this picture in Maine, just before her romance career took off. "I think about this visit often, because I felt like I was right on the cusp of something but didn't know what. I feel that way now too." Lara shot this picture in Maine, just before her romance career took off. "I think about this visit often, because I felt like I was right on the cusp of something but didn't know what. I feel that way now too." To which he would continually reply, “Just hang out in this uncertain place. Don’t fight it, just face the not-knowing and see what comes up.” I also had to face the fact that I was using success through novels as a way to make up for my perceived personal inequities. For years, I’d looked at myself, found myself lacking, and wanted to fill that void with external success. My husband would continually remind me: There is no void. He would tell me I was enough, just as I was. There was no hole to fill. I didn’t have to prove my worth.  Lara and her husband Rob, whose wisdom helped her find a new passion Lara and her husband Rob, whose wisdom helped her find a new passion So I hung out in the not knowing and, it turns out, my husband was right. I was still a writer, just maybe not a novelist. Or not only a novelist. I discovered I loved copy writing and was awesome at it. I found I had a passion for nonfiction and realized that I could to put pen to paper to fight injustice. I even got an awesome new business idea, which I’m in the process of starting up. For her part, Abby Wambach came out of her spiral too, and now she’s in a new role fighting for equity in women’s sports (particularly with regard to pay), and she’s a commenter on ESPN. I can’t recommend her memoir highly enough. I was inspired and moved. The text at the very front of the book—before chapter one, even—gets me every time I read it. Abby wrote it to her four-year-old self. It’s true of Abby. It’s true of me. If you’re struggling with any of these same things, I want you to know, it’s true of you, too: Don’t try to earn your worthiness. It’s yours by birthright. Fear no failure. There is no such thing. You will know real love. The journey will be long, but you’ll find your way home. You are so brave, little one. I’m proud of you. Do you have a facing-failure story to share? Have you ever been forced to change direction and then realized that shift was more gift than setback?

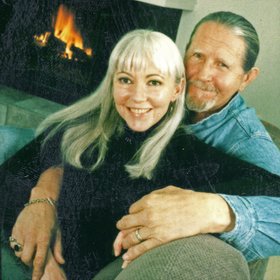

Our wedding day, 1997. Hey, I just wore those same shoes last weekend! (Photo: Cindi McDonald) Our wedding day, 1997. Hey, I just wore those same shoes last weekend! (Photo: Cindi McDonald) Recently, Ray and I passed the twenty-five year mark as a couple, and in a few months we'll celebrate our twentieth wedding anniversary. I realize those numbers aren't record-breaking—we all know couples who've been together twice as long or longer. And my mate and I aren't claiming to be paragons of contented couplehood. Still, we've learned a thing or two about durability over the years.  Sometimes it's the little things that spell love Sometimes it's the little things that spell love Here, then, is a handful of those lessons, offered not as instruction, but as an invitation for you to share your own thoughts about what makes a relationship endure, whether it's a marriage, a friendship or a close connection with a family member.

Woodland walk Woodland walk But sometimes, separate I spend most mornings practicing yoga, meditating, reading, writing and answering email, while Ray goes for walks and putters with projects in his workshop. On weekends, he might head off to a car show or woodworking demonstration, and I might play with my camera or attend a writing workshop. When we come back together, refreshed by our individual pursuits, we have new experiences and insights to share and more to talk about than whether it's time to take out the garbage.  Accentuating the positive (Photo: Donna Terek) Accentuating the positive (Photo: Donna Terek) The five-to-one formula A few years after Ray and I got together, when I was still a staff writer at the Detroit Free Press, I wrote an article about research at the University of Washington's "Love Lab." That’s where psychologist-mathematician John Gottman was engaged in a long-term study of hundreds of couples, trying to tease out behavior patterns predicted marital success or failure. One of Gottman's key findings was that lasting marriages have a magic ratio of five times as many positive feelings and interactions as negative ones. Ray and I don't keep a running tally--how silly would that be? But we seem to have developed an internal counter that prompts us to balance every tense exchange with a slew of more loving ones. It makes for a sense of safety and comfort that fosters even more warm feelings.

Hanging on! (Photo: Sally Pobojewski) Hanging on! (Photo: Sally Pobojewski) Hang on Rough patches? Sure, we have those. Doesn't everyone? And we're not always graceful about getting through them. One thing I've learned to keep in mind, though, is that everything changes. If you're patient and calm, something will shift, and you'll find a way through. Now it's your turn. What have you learned about creating and maintaining lasting relationships?

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed