Jigsaw puzzles: among the new ways of entertaining ourselves Jigsaw puzzles: among the new ways of entertaining ourselves In recent months, we’ve all had to adapt in ways we never expected: new ways of shopping, socializing, working, entertaining ourselves (jigsaw puzzles, anyone?). With Ray and me both retired, the changes weren’t as drastic for us as for many people. While there have been challenges, our adjustment has been relatively smooth, for which I’m grateful. But this home-centered span of time has also shown me how un-adaptable I am in other parts of my life and how I’ve been holding onto expectations that don’t square with reality.  Take my activity patterns, for example. For most of my life, I was an early riser. During my working years, both as an employee and as a freelancer, I usually got up at 5 a.m. and started work at 7:30 or 8:00. For a while after I retired I continued waking up and getting out of bed by 5:00 or 6:00, whether I wanted to or not. I seemed to be hard-wired to get up and get going early. In the past year or so, though, I’ve started sleeping till 7:00, 7:30, and sometimes even later. I feel like I need the sleep, like my body demands it, especially if I’ve done something intensely physical the day before, like a long hike or hours of outdoor work.  I am not a slug! (Photo: Peter Stevens) I am not a slug! (Photo: Peter Stevens) Yet every time I get up later than 6:00, I scold myself for being such a slug, and I still try to keep to a routine that’s based on getting up earlier: meditating and doing yoga before breakfast, then making and eating breakfast, doing some reading over breakfast, cleaning up my dishes and myself, getting dressed, making the bed, doing whatever else needs doing, like taking out the mail, and still being ready to start the day’s main activities (writing and book promotion in the morning; chores, errands, and recreation in the afternoon) by 8:30 or so. So every day starts with this ridiculous and totally unnecessary tension about keeping to a ridiculous and totally unrealistic schedule.  Yoga: First thing in the morning? Or not. Yoga: First thing in the morning? Or not. I’ve experimented with various alternatives—putting off yoga until later in the day, meditating before bed instead of first thing in the morning, streamlining this or that. But I’m starting to see the problem isn’t with the routines themselves, it’s with my attitude toward them. So what if some mornings I get a late start and only have time to write for half an hour instead of an hour or two? Maybe I’ll make up for it another day. And if not, so what? Yes, I feel better on days when I write and I feel off-kilter when I don’t—writing is my happy pill, after all. And yes, I get great satisfaction from seeing the word count and page count increase by the day. But if the world comes to an end, I doubt it will be because I wrote 100 words today instead of 1,000.  Ahhh, the luxury Ahhh, the luxury My reality has shifted, and it’s high time to adapt to the new one instead of clinging to the old one. The truth is, I’ll probably never again routinely get up at 5:00. So why not try to see my sleeping-later habit for what it is—a response to a physical need, not a sign of sloth--and just enjoy the luxury of being able to structure my days around it. Which brings me to another realization about reality. Structure is something else I sometimes feel conflicted about. As I wrote in a 2016 blog post, we all have our own tolerance levels for chaos and structure, and finding the right balance between them is crucial for creativity.  Structure provides a bit of certainty in uncertain times Structure provides a bit of certainty in uncertain times As I’ve been examining how to adjust my usual routines to my unpredictable sleep patterns, I’ve questioned whether I still need a routine at all. After all, I’m retired. Most of the things on my to-do list are want-to-dos, not have-to-dos. Why not just do what I feel like when I feel like it? I’ve thought a lot about that lately, and I’ve come to this conclusion: There may be a time to ditch my routines, but this isn’t it. Experts say having consistent daily and weekly routines gives us a sense of certainty in these uncertain times. The trick is to make your days consistent, with enough variety to keep boredom at bay. Sounds like exactly what I’m aiming for as I try to adapt to new realities. I’ll let you know how that works out.

Have you adapted in any surprising ways over the past months? Have you discovered aspects of your life you can let go of and others you still need to hold onto?

12 Comments

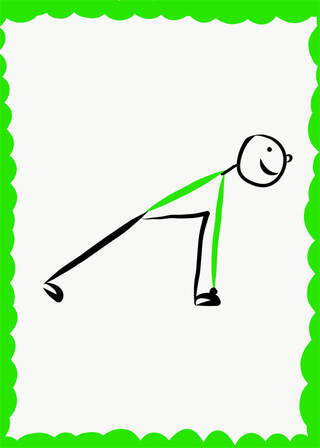

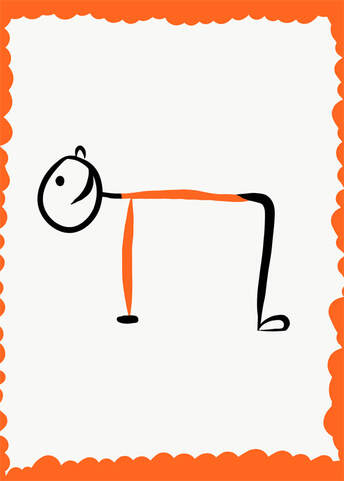

Around the middle of last week, I looked at the calendar and had a startling realization. Today would be my regular blog-posting day, and not only did I not have a post written, I could not see enough uncommitted time in the intervening days to get one written.  The Detroit book signing at Pages Bookshop The Detroit book signing at Pages Bookshop We were about to leave town for a book signing in Detroit, followed by a Michigan Nature Association dinner in East Lansing the next day, followed by a family birthday party in Northville the day after that. Then back home to Newaygo, where yoga class, a book club appearance, a medical appointment, and the library book sale setup all crowded into the next few days. There just wasn’t time to write and set up a post. Still, I didn’t want to break my commitment to post on HeartWood every first and third Wednesday. So I started scrambling and scheming. I could dig out a post I’d started a year or so ago but had set aside and never finished. Yeah, that’s what I would do. I found the post and the notes and images I needed to finish it, loaded everything onto a flash drive, and figured I’d do the work on our laptop in the downtime between the weekend events.  (Photo: Benjamin Watson) (Photo: Benjamin Watson) Great plan. Until . . . the night of the first event when—thanks to adrenaline, an unfamiliar bed, and leg cramps from the super-stylish but brutal shoes I’d worn that evening—I got almost no sleep and woke up the next morning in a fog so deep there was no way I could write anything coherent. Now that I had the time, I didn’t have the brain power. I needed to rest. I knew that. But my first impulse was to start scrambling and scheming again. I could power nap and then, if I was really efficient, still get the blog post done. Just one problem: Tired as I was, I could not fall asleep for a nap. That’s when I remembered a recent conversation with a friend who’s trying to break the habit of cramming too much into her schedule. She told me she’s cutting back on commitments and learning to rest. That’s when I knew that was what I needed to do, too. Just rest. Just then, another memory came to me: a blog post I’d written last year, when I was in a similar period of overload and had the radical idea of taking a time out.  “As soon as I had that thought, the space around me opened up,” I wrote. “My breathing slowed. I felt like I could float on air. “Such a simple solution, just stepping back and saying, ‘Whoa, there.’ Yet it's crazily easy to forget that it's an option—that when things get too hectic, maybe they don't need to be. Maybe there are things that don't have to be done, or that don't have to be done quite the way you thought they did.” I re-read those words and thought, “Who was the wise person who wrote this? Why am I not following her advice?”  "Rest at Harvest," Bouguereau, 1865 "Rest at Harvest," Bouguereau, 1865 Well, now I am. I’ve given myself permission to a take time out instead of scrambling. That other post I was going to power through and finish for today? It’ll still get done, but in a week when I can give it the time and attention it deserves. Meanwhile, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to shut off the computer and give it and my brain and body a rest.  Kirsten Voris Kirsten Voris I’m excited to introduce a very special guest this week: Kirsten Voris, co-creator of the recently-released Trauma Sensitive Yoga Deck for Kids (North Atlantic Books). The deck of 50 yoga cards for kids aged 3-12 comes with a guide for trauma-sensitive facilitation that’s grounded in the evidence-based Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) methodology and the yogic tradition of ahimsa, or non-harming. I met Kirsten through writing, not yoga—we were workshop-mates at the Tucson Festival of Books Masters Workshop a couple of years ago—and I’ve been a fan of her work ever since. When she told me about this latest project, I wanted to hear more, both about the yoga cards and the role of yoga in Kirsten’s life. I know you’ll be interested, too, so I’m sharing our conversation here. How did you first become interested in yoga? The first yoga shape I learned was headstand, and that was taught to me by a German boyfriend when I was in my twenties, so approximately 1992. Then, there was no yoga until I moved to Turkey in 2010. In Turkey I wanted to swim, but there was no way to do so cheaply. There was a yoga studio close to my house, though, so I started going. I eventually signed up for teacher training, so that I could go even more often. I did my teacher training in Ankara, Turkey (Yoga Sala, Ankara, Turkey, class of 2012!). What led you to trauma-sensitive yoga?  The yoga deck The yoga deck I was led to Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) because there were things that didn't work for me, in regards to how I was in my own body and how I was taught to facilitate yoga for other bodies. How is trauma-sensitive yoga different from other kinds of yoga?  TCTSY was developed as an intervention for complex trauma (also called complex PTSD). It is most helpful for people recovering from disturbed relationships with their bodies and the lack of agency and/or trust that can come from surviving systems of chronic disempowerment or neglect. We use the shapes (forms or asanas) from yoga to practice making choices and noticing sensations in our bodies. In a TCTSY class, participants are 100 percent in charge of their own bodies at all times. The facilitator stays on his or her own mat, and rather than setting goals or correcting or adjusting participants, simply provides them with choices for movement and highlights sensations they may feel in each shape. In order to help us keep the focus on our bodies, there is no music in a TCTSY class. What principles of yoga are most relevant to trauma-sensitive yoga?  From Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga, we focus on Asana, or the movement practice. And within the movement, Dhyana, or meditation. In TCTSY we use our bodies and sensation in our bodies as the focus of meditation or mindfulness, as opposed to the breath. Instead of returning to our breath, we’re returning to our bodies when we get distracted. I might invite a client to notice their breath if I know them well. However, in general we don’t work with the breath. For some people, feeling their own breath moving can be a very potent trigger. Some yogic breath practices trigger anxiety and, with Pranayama (breath control), there is a goal involved: to become more centered, more calm, more energized. In TCTSY there is no outcome we are looking to achieve. Ahimsa, which means non-harming, is a part of everything we do. We want to empower, not disempower. I am not someone who can teach others how to heal. I can be a witness, though, to someone’s healing. And I can hold a space for healing. Judith Herman, a therapist, researcher, and author of Trauma and Recovery, inspired so much of what we do. She has another way of putting this. She wrote: “No intervention that takes power away from the survivor can ever foster her recovery no matter how much it appears to be in her immediate self-interest.” I love that. My body knows how to heal. So does yours. How did the yoga deck project come about? Brooklyn Alvarez Brooklyn Alvarez I met co-creator Brooklyn Alvarez in our 300-hour TCTSY facilitation training. We were assigned to be buddies. We spoke every week for nine months. We had both done some facilitation with kids with the available yoga cards and didn't like them. One week in our supervision meeting we told Dave Emerson (director of the center), what we'd been talking about. He told someone at North Atlantic Books. Some time later, Dave announced that North Atlantic Books wanted to publish our deck of trauma-sensitive yoga cards for kids, which up until then, we had only been talking about. It was pretty mind-blowing how that happened. Dave read through the pamphlet and helped us in so many different ways with ideas for content and questions around language and feedback on the cards and the pamphlet. He let Brooklyn and me have our own process when it came to resolving issues that came up during the creation of the final product. He was our first editor. I'm really happy to be associated with him in this way and to have him associated with us and the cards. How do you envision the yoga deck being used?  Lots of kids love to move. This is an opportunity to harness that and provide kids with the opportunity to experience choice—in their bodies. And maybe notice sensation in their bodies, to help them ground in the present moment, which is the only place we can feel a sensation. I'd like the cards to be used by people who love kids who have been through terrible things. Anyone can help a child heal. TCTSY practitioners who are therapists can use cards in session with their clients. Foster parents can use the cards to engage with kids in their care. The cards can be a supplemental activity or the main attraction. The pamphlet comes with ideas for group activities involving the cards and practices for one-on-one facilitation or small-group facilitation. And all of these are suggestions. What is important is creating a sense of connection and safety for children. Caregivers can do this by practicing along with the kids in their care, not asking kids to do something and then standing back and watching. Yoga card time can be family time. Time to put down your phone, turn off the TV, and practice being in your body. Everyone practices together: the youth, the moms, the grandmas, the foster dads. Each person noticing their own bodies. How has your own yoga practice evolved over time? My yoga practice started out as anxiety management through overdoing it. I was in class every day and it was vinyasa or ashtanga class. I wanted to stand on my head and balance on my arms. I wasn’t interested in learning to be grounded in my body. Or still. I could not tolerate savasana, or rest. I kept my eyes open. I didn’t like being adjusted or touched. Then, I began to get injured. I have healed-over hamstring tears. I have tendinitis in my left deltoid. In the wake of that particular injury, I couldn’t raise my arm over my head for one year. I discovered the limits of self-medication through exercise. I started to slow down—out of necessity. My favorite teacher in Turkey had a Yin Yoga class that I began attending. It was very difficult for me to hold shapes for long periods of time and give myself over to them. But listening to her guide us through it, as she talked about all the different muscles and meridians we were touching though our practice, helped. (I dedicated my yoga cards to her.) Eventually I began to notice and feel my body and realized that, before I got injured, I couldn’t feel my body at all. And because I couldn’t feel it, I couldn’t make good choices for my body. After graduating from teacher training, I went to a week-long Yin training with Bernie Clark, who introduced me to the idea that adjusting people based on our idea of how a shape needs to look can hurt people. Everyone needs to find their own shape. Since moving back to the US, my yoga is mostly at home. Learning and facilitating TCTSY has made it even more difficult for me to find yoga classes I like, because now I am super-empowered to say what I don’t like (I don’t like to be touched or adjusted or told what to do), and I now know there is a kind of yoga that doesn’t require me to do that to other people. For the past two years I have been involved in an Open Floor Dance community here in Tucson. This is a conscious dance practice. You dance however you want, and you stay with yourself. I’m still learning, and this is the scary leading edge of my evolution as a human being. And it wouldn’t have been possible, without TCTSY. Anything else you’d like to add? Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga is very new and very special, and the community is not that large. It has felt amazing to create something that I believe so strongly in, in concert with other humans who are equally passionate about the innate power we all have to help ourselves heal from terrible things--without having to talk about those terrible things. Through movement. The Trauma-Sensitive Yoga Deck for Kids can be ordered through independent bookstores, IndieBound, Penguin Random House, and other online booksellers. ISBN: 9781623173289, $25.95 More about Kirsten and her co-creators KIRSTEN VORIS (RYT-200, TCTSY-F) is a former secondary school teacher and adult educator who completed her initial yoga certification in Ankara, Turkey. Her interest in yoga as a tool for personal integration led her to Yin Yoga and the research-based Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY). She has facilitated TCTSY for volunteer aid workers in Cusercoli, Italy and brought TCTSY to therapists through PESI trauma training retreats in Sedona, Arizona. In addition to facilitating TCTSY for private clients in and around Tucson, Arizona, Voris has been the TCTSY provider for youth and children through a tribal health service in Southern Arizona. She offers an introduction to TCTSY to fourth year medical students and medical residents at the University of Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine. BROOKLYN ALVAREZ is a clinical psychologist-in-training (doctoral degree expected 2021), certified Kripalu yoga teacher, and avid student of Buddhist psychology and mindfulness meditation. Alvarez's personal and professional experiences have inspired in her a fervent aspiration to specialize in the treatment of developmental trauma and, ultimately, to disrupt systemic hegemony. DAVID EMERSON is the founder and director of Yoga Services for the Trauma Center at the Justice Resource Institute in Brookline Massachusetts, where he coined the term "trauma-sensitive yoga" (TSY). He was responsible for curriculum development, supervision and oversight of the yoga intervention component of the first of its kind, NIH funded study, conducted by Dr. Bessel van der Kolk to assess the utility and feasibility of yoga for adults with treatment-resistant PTSD. Emerson has developed, conducted, and supervised TSY groups for rape crisis centers, domestic violence programs, and residential programs for youth, military bases, survivors of terrorism, and Veterans Administration centers and clinics. In addition to co-authoring several articles on the subject of yoga and trauma, Emerson is the co-author of Overcoming Trauma through Yoga, (North Atlantic Books, 2011) and author of Trauma-Sensitive Yoga in Therapy (Norton, 2015). He leads trainings for yoga teachers and mental health clinicians in North America, Europe, and Asia.

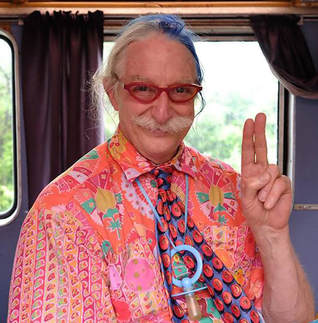

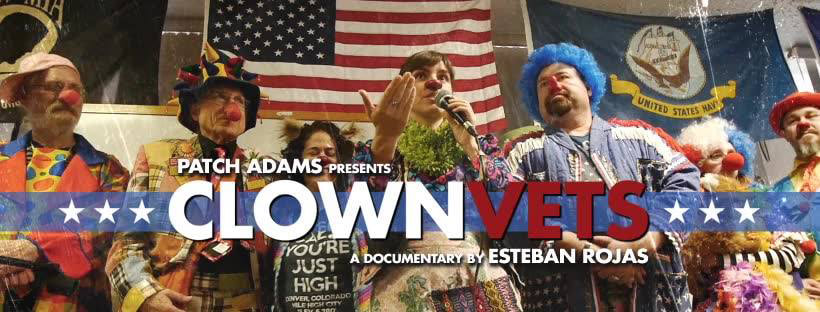

Vietnam veteran Mike O'Connor* Vietnam veteran Mike O'Connor* The bearded man with the gray ponytail sits at a table, alone and looking like he wants to keep it that way. When he speaks, it's to talk about a time in his youth when he decided "I should not befriend new people, because they're likely to die." Even now, he goes on to say, "I still don't get too close to many people." Flash forward to another scene. Same man, same beard and ponytail, tattoos visible on his forearms, but now he's prancing around in a red tutu over striped pants, sporting a red nose, a pink ball cap and an oversized, polka-dot tie and yukking it up with a gaggle of kids and a bunch of other burly guys who are just as outlandishly attired.  Mike in clown mode* Mike in clown mode* What accounts for the shift between scenes? The man in the red tutu is 71-year-old Vietnam veteran Mike O'Connor, who summoned a different kind of bravery to take part in an experiment in humanitarian clowning, traveling to Guatemala with a group of other veterans to spread smiles in hospitals and orphanages. In the process, he and the other Vets stepped out of the "suffer zone" into a more playful, loving space. Clownvets, a program of physician Patch Adams's Gesundheit! Institute, is the subject of a documentary film-in-progress, and in a bit I'll tell you how you can help the filmmakers finish, distribute and promote the film.  Mark Kane, AKA Marcos the Clown Mark Kane, AKA Marcos the Clown But first, a bit of background. I first heard about the Clownvets project from my neighbor Mark Kane, a licensed psychologist who has seen from his work with veterans how trauma affects the mind, body and spirit. In fact, it was Mark's exposure to Vietnam veterans as a conscientious objector working with the American Friends Service Committee years ago that prompted him to become a psychologist. "Post-traumatic stress, in a variety of names, has been with us since the beginning of time," says Mark. "It's not really a disease like polio is . . . It's normal people reacting normally to very un-normal circumstances." Statistics on the impact of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are sobering. In the U.S., more than twenty Veterans commit suicide daily. Many more experience physical and psychological symptoms that ripple out to affect their families and communities. As a step toward relieving some of that suffering, Adams and the Gesundheit! Institute came up with the idea of introducing Vets to humanitarian clowning.  Patch Adams* Patch Adams* Known for his work with warriors experiencing PTSD, Mark was asked to help recruit Vets for the Gesundheit! project. All he knew about Patch Adams at the time was that Robin Williams had depicted him in the eponymous 1998 movie, but Mark quickly learned more about the clowning physician and got onboard with the project. Getting Vets into tutus and rainbow wigs isn't as crazy an idea as it may seem. The nonprofit Gesundheit! Institute bases its holistic brand of medical care on the notion that the health of the individual is closely tied to the health of the family, community, society and world. A leader in the development of therapeutic clowning, Gesundheit! has been sending trained volunteers around the world since 1985 to clown in healthcare settings and distressed communities. They soon learned that it wasn't only the people on the receiving end who benefited from silliness and "spontaneous, interactive play." The clowns themselves—even those who'd started out depressed—came home happy. In 2015, the first cohort of Clownvets traveled to Guatemala, and the experience was transformative. "They saw that they could be part of the solution, instead of causing devastation," says Mark. In the film, several of the Vets, including Mike O'Connor, reflect on the experience.  Clowning helped bring Mike out of his shell* Clowning helped bring Mike out of his shell* "I never thought that I would interact with people the way that I did," Mike says. "It's probably a good thing for me, because I do like to isolate, and I couldn't there. It brought me a little bit out of my shell and helped me to interact with people once I got back home." When the first group of Clownvets returned, they helped recruit volunteers for a second trip in 2016.  Esteban Rojas* Esteban Rojas* That's when Chilean filmmaker Esteban Rojas, a longtime friend and collaborator of the Gesundheit! Institute, got involved. What Esteban saw "blew his mind," to quote from an online write-up about the project. "Listening to their life stories, hearing the horrors that they went through, but also seeing how their faces changed while trying the clowning, convinced him that this story needed to be told." A month later, Esteban traveled to West Michigan to film Mark and some of the Vets in their daily lives and interview them about their experiences. Mark took on the role of producer and has been working closely with Esteban, co-editor Luis Bahamondes, and executive producers Charlotte Huggins and John Glick on the film, which includes material filmed by a different camera crew on the 2015 Veterans clown trip. Veteran Mike O'Connor has signed on to the film project as a consultant.  Eldon Howe Eldon Howe Another friend of ours, Eldon Howe, is also involved with the film. In his day job, Eldon is owner of Howe Construction, a company that builds ecology-based, disaster-resistant homes all over the world. But he's also a talented singer-songwriter who expresses himself musically through guitar compositions. Some of his music is included in the film's soundtrack—the perfect accompaniment to footage of our West Michigan environs. I had a chance to view an early version of the film, and to say I was impressed and moved is a huge understatement. Though I had talked with Mark on many occasions about the Clownvets project, I never quite grasped the enormity of its impact until I saw on screen how the Vets and the people with whom they interacted were lifted up through clowning. Wearing silly hats, splashy costumes and of course, red noses, the Clownvets and Gesundheit! staffers gently coax smiles out of children and adults who are living with serious physical and emotional conditions. They hold hands, play with puppets and blow bubbles and kisses. As Mark puts it, "the red nose works as an excuse to connect these men and women with love, compassion, laughter and friendship, things that for these heroes seemed forgotten." "Clownvets" is well on its way to becoming a high-quality, 90-minute feature film, but it has hit a roadblock. Funding has run out, yet there's still more work to be done: filming additional scenes and interviews, finishing the editing, tending to other technical details. That's where you can help. First, view the movie trailer here. Then, please consider making a donation in support of the project. Visit the Gesundheit! Institute's "Donate" page, and under the heading "How would you like to support our work?" select "Support the Veterans Clown Trip Film Project." You're also invited see a preview of the film and meet some Clownvets in person at a "Fun-Raiser" this Friday, November 17, 6-10 p.m., at Ferris State University's University Center, 805 Campus Drive, Big Rapids. Short of cash? Too far from Big Rapids to make the preview? You can still help by spreading the word about this project on social media. The Clownvets will reward you with a slew of heartfelt smiles, and maybe they'll even blow you a kiss. * Photos: Gesundheit! Institute

It was the Friday before Memorial Day, that gateway to the good times of summer, and I was anticipating the weeks ahead. Sunny days for hiking, bicycling, kayaking, diving into household and outdoor projects, and just plain getting out and doing things without having to negotiate snow and ice. My mind was so occupied with such leisurely thoughts, I hardly noticed the ache across the top of my foot that morning. Around the time I was ready to leave for that afternoon's trek with the Wander Women, the ache asserted itself more aggressively, and I considered skipping the hike. But it was such an ideal hiking day—blue-skyed, cloud-fluffed, warm but not hot—I couldn't resist. And anyway, my foot felt much better in my hiking shoe. Until about three miles into the hike. Then it really started to hurt. I limped the last mile and a half, drove home, iced the foot and brushed aside Ray's suggestion to visit Urgent Care. It didn't hurt that much. Not enough to interfere with our weekend plans. After hobbling through the weekend and holiday, I finally admitted the foot wasn't getting any better. An x-ray revealed the reason: a fracture of the third metatarsal. I was fitted with a clunky walker boot, given a referral to an orthopedic surgeon and sent home to contemplate this turn of events. Clearly, summer would not be quite as I'd envisioned. I didn't waste time moping, though. No siree, I sat down and made a list of things I still could do: writing, reading those piles of accumulated books and magazines, answering email, calling friends, making phone calls and writing letters in support of causes, creating collages, meditating, planning our fall vacation, organizing and editing photos, even shooting new photos of critters from the back porch. Good for me! Lemonade from lemons and all that, right? Yeah, about that . . . A few days after making that upbeat list, I got restless and pulled out the list for inspiration. All those housebound activities didn't seem nearly as appealing as when I'd written them down—especially when another sunny day taunted me just outside the windows. Plus, I'd realized that the list of things I still could do also included things I'd just as soon not: paying bills, cleaning out files, and performing a surprising number of household and chores. B-o-r-i-n-g.  The last subverted summer, 2006, after a little motorcycle mishap (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) The last subverted summer, 2006, after a little motorcycle mishap (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) Then I moped. But moping got boring pretty quickly, too, so I figured it was time to give myself a pep talk on adaptability and making the best of a disappointing situation. Fortunately, My Self is something of an authority on the subject, having had ample experience with subverted summers: three previous foot fractures and a spinal fracture over the past 24 years, each one occurring sometime between Memorial Day and mid-July.  This is what I had in mind for the summer of 1995 (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) This is what I had in mind for the summer of 1995 (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) I'd even written a magazine article about the summer I broke my back—the summer we'd planned a month-long motorcycle trip through the Blue Ridge Mountains, as well as weekends of Rollerblading and bicycling in the park. The summer with a few definite plans and plenty of room for following whims.  Instead, I ended up with a back brace and a black eye from a fall down the stairs (on the way to do laundry -- a very hazardous activity!) (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) Instead, I ended up with a back brace and a black eye from a fall down the stairs (on the way to do laundry -- a very hazardous activity!) (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) As I wrote in the article: When I thought about happenstance, of course, I was envisioning the merry kind that brings opportunities and delights. But when serendipity stepped in and made choices for me, it knocked me flat . . . What I didn't realize was that fate, in fact, had intervened to give me the break I had longed for—not exactly the way I had imagined it, but a break all the same. With my choices suddenly so limited, life had to get simpler. Time had to slow down. Then, as now, I occupied myself catching up on articles I'd clipped and saved to read when I found the time. One, on the unlikely topic of the benefits of poor health, made the point that having to step off the treadmill of everyday life and let things go on without your participation can be a chance to reflect and make needed changes. That I did. I reflected on the work I was doing and how I'd like it to be different—a train of thought that led to a new, more creative way of working. I also used the time to experiment with various kinds of writing and explore visual arts in ways I'd not had time—or nerve—to try before. In the process, I learned to care more about satisfaction than accomplishment, to let interests drive me more than ambition—lessons that set the stage for the kind of life I'm living now (or trying to).  Once again off the treadmill (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) Once again off the treadmill (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) Back then, I was stepping away from a hectic, deadline-driven life. This time, the treadmill I'm stepping off moves at a significantly slower rate. Still, the shift in activities and expectations should offer a chance to reflect and consider new directions. I wonder what I'll discover this time and where those discoveries will lead. Meanwhile, my change of summer plans also means changes of plans for HeartWood. I had envisioned gathering blog material in trips to festivals, friends' gardens, local labyrinths and other points of interest. Some of that still may happen, but for a while at least, I won't be venturing out as much as I'd imagined I would.  This can be YOU! (Pipe and fedora optional) This can be YOU! (Pipe and fedora optional) That's where you come in. I hereby deputize all HeartWood readers to be official correspondents. If, in your summer ramblings, you have experiences you'd like to share in words, pictures or both, I'll be happy to give you space to do that here at HeartWood. Just get in touch and we'll work out the details. I hope you'll take me up on the offer! |

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed