|

In a blog post earlier this year, I claimed not to be much of a souvenir shopper. While it's true that I don't cart home a lot of tchotchkes from our travels, I must confess to a weakness for one particular kind of memento.  I'm a sucker for embroidered patches from state and national parks.  Heavily inVESTed (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) Heavily inVESTed (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) My patch-collecting habit began back in my motorcycling days. Bikers love to load up their leather vests with pins and patches—some documenting attendance at rallies, others bearing pithy slogans, and still others memorializing fallen comrades. I was no exception: my vest became so loaded with loot, I could hardly remain vertical when I put it on.  Still, I collected. When Ray and I traveled by motorcycle and stopped at parks, preserves, and other points of interest, patches were the perfect keepsakes: lightweight and easily stowed in a saddlebag. As I look through my collection, I see patches from Toltec Mounds in Arkansas, Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, and Land Between the Lakes on the border of Kentucky and Tennessee, all collected on one especially memorable motorcycle trip to and from a class reunion in Oklahoma.  Once I got started, I couldn't stop, even when we traveled by car or motorhome and had more room for stuff. I could easily pass up shot glasses and key chains in gift shops, but patches? Never! So the collection grew, with additions from Niagara Falls, Pictured Rocks, Pompey's Pillar, Denali National Park, Grand Canyon, and another couple dozen or more locations.  Soon, I realized my travel patches needed their own home. Not only was my motorcycle vest loaded up, but a patch from Walden Pond just didn't look right next to one declaring "Die Yuppie Scum!" (Okay, I didn't actually wear that one on my vest.)  Perfect for patches (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) Perfect for patches (Photo: Ray Pokerwinski) As I was poking through my closet one day, it dawned on me that I already owned the ideal travel patch display garment: a safari-style vest I had bought for a trip to Australia in 1986 and had little occasion to wear since then. I dug it out and started decorating it with some of my favorite patches. One of the first: Sleeping Bear Dunes—our annual fall color tour destination—followed by Tahquamenon Falls, Acadia National Park, and Yellowstone.  My patch-laden vest became a thing of beauty. From time to time, I'd slip it off its hanger and admire it. I'd lay out all the patches I hadn't yet attached and figure out which ones to add next and where to put them. But the one thing I never did was actually wear the thing. Because, well, it may be a thing of beauty, but it's a very dorky thing of beauty. I took to calling it my Junior Ranger vest and treating it like a joke. Still, I kept collecting patches, vowing that someday I'd get up my nerve and wear the vest somewhere.  The Wander Women, outfitted for the trail The Wander Women, outfitted for the trail When I joined the Wander Women, a local women's hiking club, I thought the perfect opportunity had arrived. The Wander Women are an accepting, encouraging group. They dress for comfort and protection, even if that means wearing funny-looking hats and tucking pant legs into sock tops. The Wander Women wouldn't make fun of my vest. Would they?  More pretty patches More pretty patches When I returned from our latest trip to the Southwest with a whole new stash of patches, I added them to my vest, determined to debut it on the next Wander Women hike. But that day it was too cold for just a vest over my shirt. So was the next hiking day. Then the weather turned warm, and—oops, too warm for anything more than a tank top. So as of yet, no "big reveal" for the vest. But the next patch I hope to add is going to be so special, I doubt I'll be able to keep it under wraps.  Wander Women on the North Country Trail Wander Women on the North Country Trail Here's why: The Wander Women have set a goal of hiking--segment by segment--all 65 miles of the portion of North Country Trail that runs through Newaygo County (or at least the 50 off-road miles, as the trail follows roads in a few sections). And it happens that the North Country Trail Association has a Hike 50 campaign underway, encouraging people to hike 50 miles of the trail over the course of the year. (There's a Hike 100 campaign, too, but first things first.)  North Country Trail patches, including the one for the Hike 50 Challenge (Photo: North Country Trail Association) North Country Trail patches, including the one for the Hike 50 Challenge (Photo: North Country Trail Association) Anyone who completes the whole 50 miles gets—you guessed it—a patch. I've been logging my miles on the North Country Trail since March, and I'm up to 23 miles now (plus more miles on other trails, but those don't count toward the patch). With the Wander Women's target to motivate me, I've got that patch in my sights. Once I get it, you can be sure I'll wear my vest with pride. Really. I will. Unless it's too hot. Or too cold. Or too . . . you know, whatever.

21 Comments

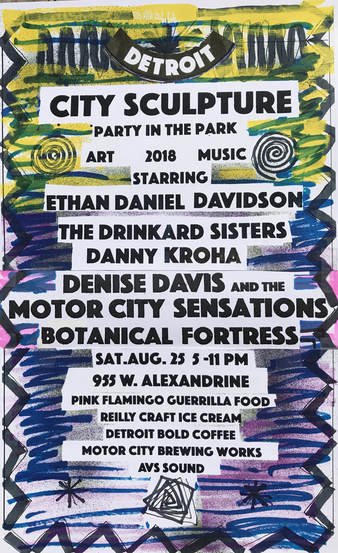

Dreams, determination and a life's artistic work—that's what transformed a nondescript vacant lot in Detroit into an urban sculpture park.  Sign at the entrance to City Sculpture Sign at the entrance to City Sculpture City Sculpture is the creation of Robert "Bob" Sestok, who has been making art in Detroit since the 1960s. I met Bob in the early '80s, when the neighborhood now called Midtown was in its grittier incarnation as the Cass Corridor. Bob was already a fixture in that community, as one of the founders of Willis Gallery and part of the Cass Corridor Movement, a group of artists whose unconventional methods and materials reflected the crumbling, post-industrial environment of the time and were influenced by the abstract expressionists of the 1950s. Some of those artists, including Bob, were featured in a 1980 Detroit Institute of Arts retrospective exhibition, "Kick Out the Jams: Detroit's Cass Corridor, 1963-1977." (The title was a nod to the debut album of the rock band MC5, which played at the opening of an art show Bob organized in 1972.)  Bob Sestok with one of his sculptures Bob Sestok with one of his sculptures I've always been amazed at Bob's ability to segue seamlessly from drawing to painting to printmaking to creating massive metal sculptures. Many of those sculptures are displayed in public spaces in Detroit, its suburbs, and other locations around Michigan and beyond. Other pieces accumulated over the years in the alley behind Bob's studio. But Bob had a bigger vision for those works: a public space to display the sculptures right in the neighborhood where they were produced. He didn't have to look far to find a good spot. A block away from his home and studio was a city-owned vacant lot that fronted the John C. Lodge Service Drive. A conscientious neighbor and his kids had been mowing the lot and keeping it trash-free, and when that neighbor died, Bob took over the job.  Bob Sestok atop one of his sculptures (Photo: Roy Feldman) Bob Sestok atop one of his sculptures (Photo: Roy Feldman) "I was cutting the grass and thinking, 'Why don't I own this?'" Bob recalls. So he bought the property from the city and then spent about a year cleaning it up, repairing the sidewalks, installing a fence and pouring concrete slabs for the sculptures. Once that work was done, he spent another week or so moving and positioning the sculptures.  "As soon as I did that, all of a sudden the news media got wind of it, and I was on all the television channels and in the newspaper," says Bob. "It was quite a big bang." And quite a change for an artist who has always been more comfortable just doing his work than being in the public eye. "I kind of shy away from stuff like that," says Bob, "but I was willing to do interviews and tell people about the work in the park. So I'm a little more public today than I have been in the past, but that's the nature of having a space like that. And it's a fun thing to have. People go there from all over the place." Like Tyree Guyton's Heidelberg Project and Olayami Dabls's MBAD African Bead Museum, City Sculpture has become a destination landmark, as well as a showcase for an individual artist's life work. "Tour buses pull up, school buses pull up, kids get out, all kinds of people," says Bob. "We give tours. People contact me if they want to have the artist's viewpoint of the park. I do a little talk. We've had thirty or forty people at a time."  The poster for this year's City Sculpture Party in the Park The poster for this year's City Sculpture Party in the Park He also throws a party in the park every summer. "It's kind of a big thing for me to put together," he says, "but I get local musicians and it's a lot of fun." This year's event, scheduled for Saturday, August 25, features Ethan Daniel Davidson, The Drinkard Sisters, Danny Kroha, Denise Davis and the Motor City Sensations, and Botanical Fortress.  I'd been hearing about the park since it opened in 2015, but hadn't had a chance to visit it until a few weeks ago, when Ray and I drove down to Detroit to have lunch with another old Cass Corridor friend who was back in town for a couple of days. We arrived a little early, and since the restaurant where we were to meet our friend was only a few blocks from City Sculpture, we made a side trip to the park to check out Bob's creations.  Seeing so much of Bob's work in one place was truly impressive. Thirty-two sculptures of welded steel, crushed aluminum, car parts, and garden implements are artfully arranged around the well-maintained site. A bench beneath a tree offers a place to sit and reflect. Even with traffic whizzing along on the Lodge Freeway, City Sculpture feels like a haven. The works on display reflect Bob's eclectic approach to making art, a style he has described as the absolute lack of a single, cohesive style.  "When people ask who made all these, I tell them, 'Well, they could've been made by a lot of different people, because nothing looks the same.' There's a lot of diversity in my work. I think that keeps me moving forward."  One of the murals at the Edward W. Duffy Company One of the murals at the Edward W. Duffy Company A graduate of the College for Creative Studies (then known as the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts), Bob is known not only for his sculptures, but also for his paintings, including both permitted and unauthorized public art pieces. Among the first were murals commissioned in the early 1970s for the Edward W. Duffy Company, a pipe and tubing supply business. More recently, Bob created a mural for musician Jack White's Third Man Pressing, a vinyl record manufacturing plant in the Cass Corridor. White remembered seeing the Duffy Company murals when he was in high school, and once he became a successful musician with his own factory, he got in touch with Bob to commission a mural for the record-pressing facility. As for unsanctioned street art, Bob says he's pretty much "retired" from that line of work. "All the buildings I painted on were rehabbed or torn down. I said, I don't want to have my art destroyed completely." The desire to preserve his art also has him thinking about the future of City Sculpture. "Now I'm becoming more of a businessman and trying to get corporate sponsorships," he says. "I created a nonprofit, which I'm thinking to turn into a foundation to manage the park." He plans to turn over management of the foundation to his daughter Erika, who grew up in the neighborhood and has experience in park management. Meanwhile, Bob keeps making art and displaying his work in different venues. He recently delivered five sculptures to Michigan Legacy Art Park at Crystal Mountain in Thompsonville, and he's currently in a show at Marshall M. Fredericks Sculpture Museum in Saginaw. "I'm a lucky guy," he says. "I've got a job for my life. I can't stop—I just keep doing my thing. I like to discover things and challenge myself. If you don't challenge yourself, you're not learning anything. You have to push yourself and reach outside of your comfort zone in order to be prolific." With nearly one hundred sculptures, more than five thousand drawings, and some one thousand paintings completed to date, he should know. City Sculpture is located at 955 West Alexandrine in Detroit. To help support City Sculpture, visit https://www.citysculpture.org/donate/ Bob Sestok has exhibited at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), Cranbrook Museum of Art, and Marianne Boesky Gallery (New York City), among others, and had work in ArtPrize 2009. His work is held in numerous collections, including the Detroit Institute of Arts, Cranbrook Museum of Art,and Wayne State University. He has received grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts and The Kresge Foundation.

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed