|

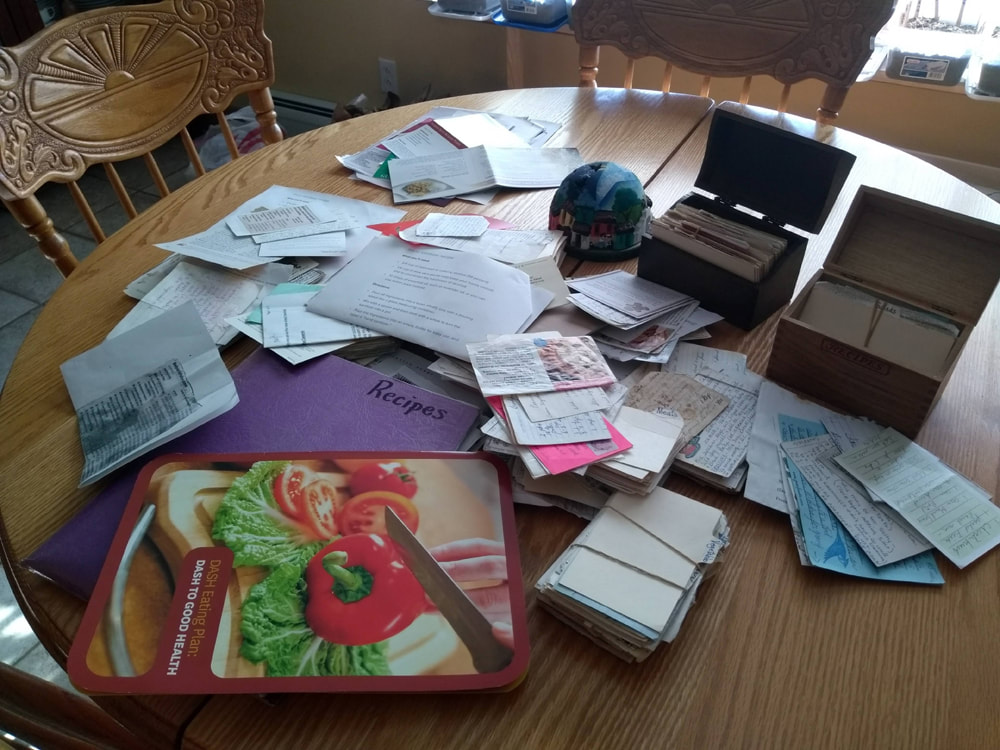

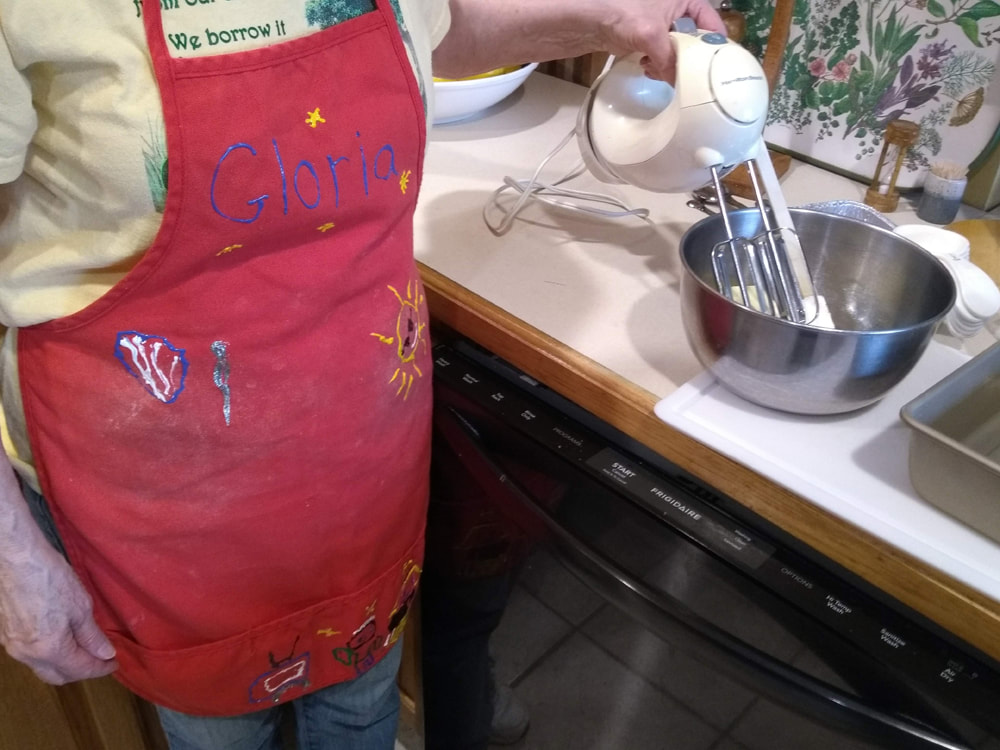

Around mid-December, a friend posed this question on Facebook: What’s something that you thought you’d do this year during your changed world due to the pandemic, but turns out you didn’t do?  Did you plan to learn tai chi during the past year's downtime? Did you plan to learn tai chi during the past year's downtime? She got things rolling with her own confession that she’d intended to learn and practice tai chi using a DVD that had been recommended, but after trying it couple times, she never returned to the practice.  Was baking bread on your pandemic project list? Was baking bread on your pandemic project list? In the comments under her post, a few other people said they’d planned to learn something new—a language or a skill like baking bread—or spend more time doing something they already enjoyed, like painting. Or something they perhaps didn’t enjoy so much—working out, for instance—but resolved to do. Yet even in their changed worlds, days filled up with routine tasks like bill-paying, yard work, and household chores, on top of which some had the added responsibility of teaching homebound children. Then there were those who were sure they’d use their extra home-time to finally get organized. Garages, closets, storerooms all would be neat and orderly by the end of 2020. That didn’t always happen, either. Turns out those tasks are no less tedious when you have time for them than when you’re occupied with other things. I made that discovery myself. After an initial blitz of cleaning out cabinets, drawers, and closets, culling stuff, stuff, and more stuff, I hit a wall. Or maybe it was that warm weather arrived, and outdoor projects had more appeal.  I made some new paths through the woods, but other outdoor projects remained unfinished I made some new paths through the woods, but other outdoor projects remained unfinished About those outdoor projects: there again, I had big plans for finishing the landscaping we’ve been trying over the past few summers to complete. I did make progress, but finish? Nope. Maybe next summer. What about you? What became of your intentions for 2020? What got done, and what got left undone? Does the answer to that question reflect a shift in priorities, or merely an adjustment to reality?  Some days, an excursion to Lake Michigan mattered more than getting things done Some days, an excursion to Lake Michigan mattered more than getting things done My answer to that last question is, a little of both. Working on my novel-in-progress became a higher priority than cleaning out every last file drawer. Organizing Zoom readings of my memoir took precedence over reorganizing my wardrobe. And some days, watching movies, playing Scrabble, or going for a long drive with Ray—compensating for the concerts, readings, and other live events we could no longer attend—felt more important than accomplishing anything at all. Now, a new year lies ahead, but life isn’t likely to return to normal (whatever form that takes) for at least another few months. So how to spend the remainder of our reconfigured time? Tackle more tasks or take advantage of these more spacious days to let our imaginations wander and our creative impulses reign? I gave some thought to that question as 2020 wound down. While I had no trouble coming up with lists of household projects to finish and other business to take care of, I realized my choices for the past year pointed to the way forward for the next. The things that yielded satisfaction—writing and other creative work, keeping in touch with friends, spending time with Ray—are the things I want to devote the most time and energy to. Not that I’ll ignore the rest. Checking off mundane tasks brings its own kind of satisfaction. But this time next year, I have a feeling the number of chores I’ve crossed off won’t matter nearly as much as the kind of contentment that comes from creativity and connection. (Oh, hey, that sounds like a catchy tagline for a blog!)

10 Comments

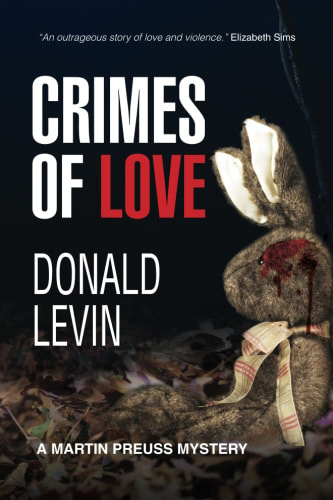

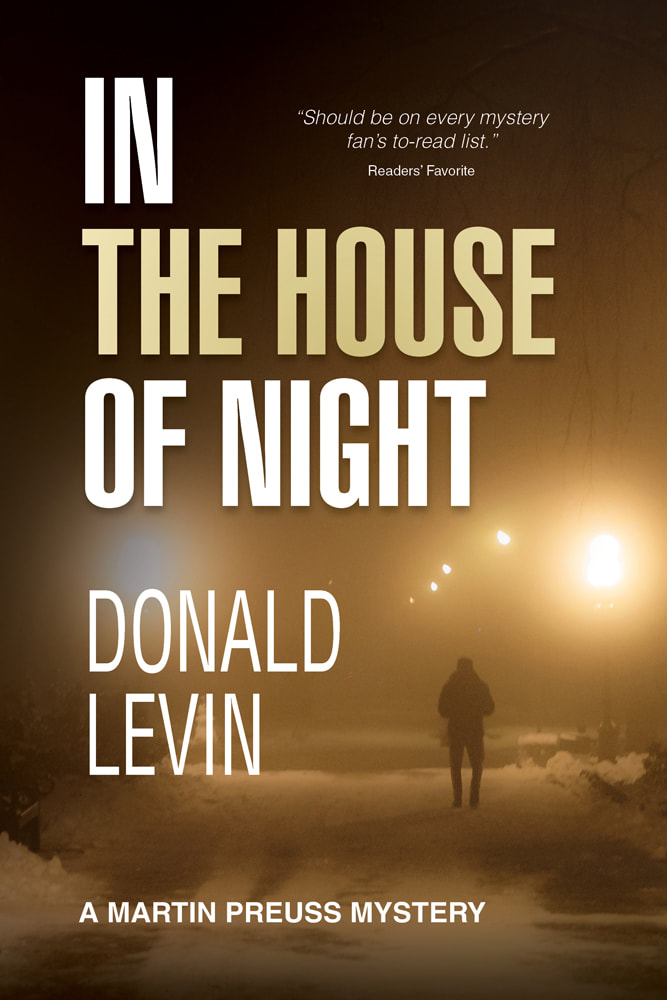

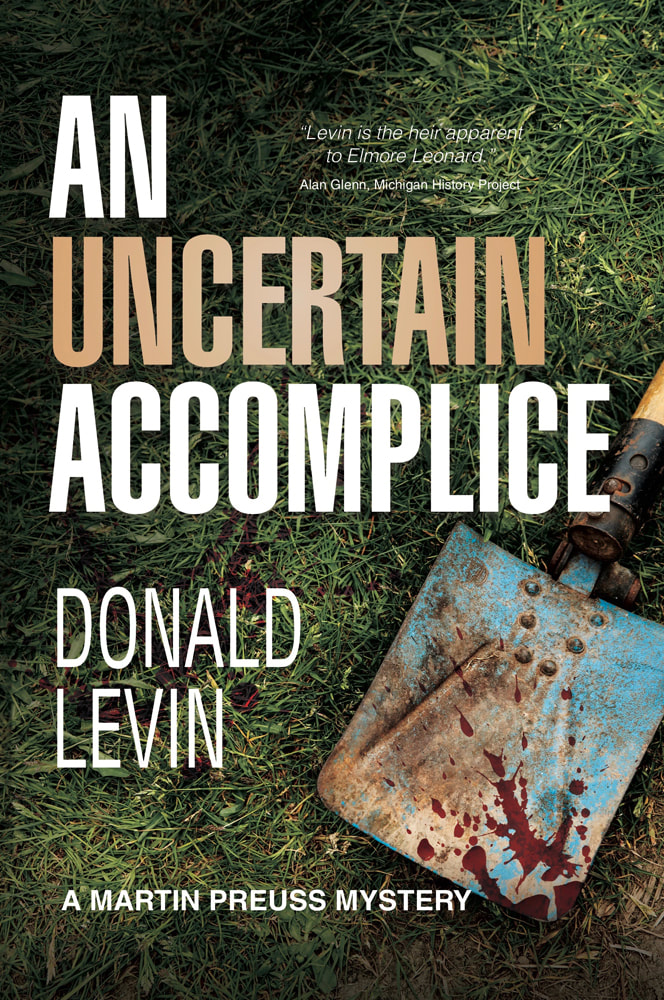

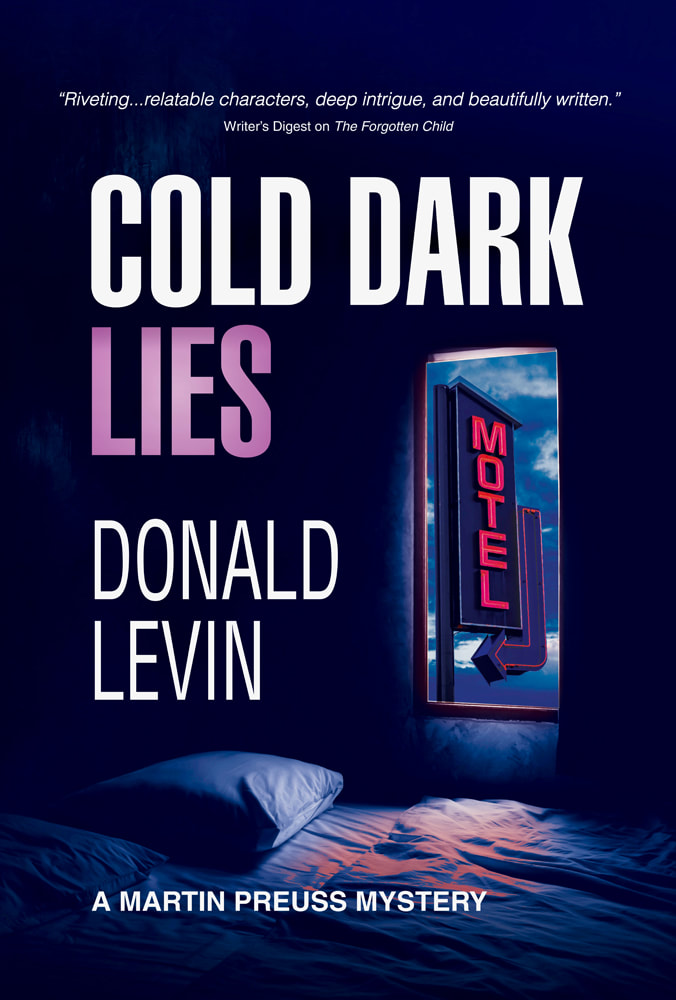

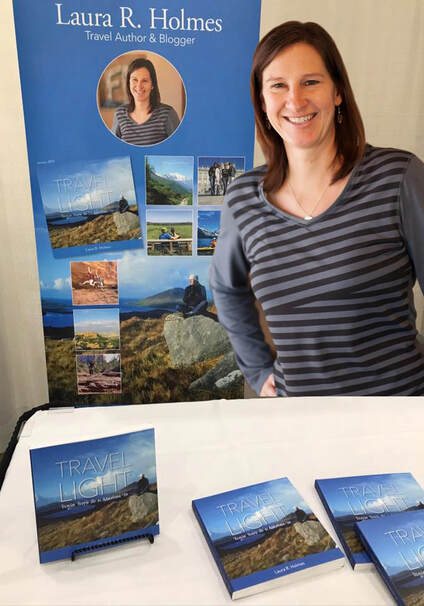

With most in-person author events still on hold indefinitely, I'm devoting one blog post each month to an author interview. Today's guest is Donald Levin, author of seven mysteries in the Martin Preuss series, as well as the novel The House of Grins (1992) and two books of poetry, In Praise of Old Photographs (2005) and New Year’s Tangerine (2007). The latest book in the Martin Preuss series, In the House of Night, officially launches Tuesday, October 6. You have published six books in the past nine years, with a seventh due out soon. What writing (and other) habits contribute to your productivity?

My experience taught me that if you’re going to be a writer, you need to approach it as a profession. You can’t sit and wait for inspiration, any more than a surgeon can wait to be inspired before performing an operation. You have to make yourself write, even if you don't feel like it. Inspiration and creativity come from writing, not the other way around. Once I started as a serious creative writer—producing novels, short stories, and poetry—I transferred that workmanlike attitude and those work habits that I developed. So when I’m working on a novel, I make sure I’m at work at the same time every day, and put in a full day of writing with a quota of 1,000 words. I’m very fortunate that I was able to retire from teaching five years ago so I have been able to devote a lot of time to writing. But even before I retired, I made time to write while working full-time. It can be done. According to your website, you have worked as a warehouseman, theatre manager, advertising copywriter, scriptwriter, video producer, and political speechwriter as well as professor and dean at Marygrove College. How does this varied work background serve you as an author?

And second, I get bored easily (the polite way of saying the same thing is, I have always been intellectually restless) so I’ve always wanted to be as versatile as possible. This not only helped me find work because I could do a lot of different things, but having all those different kinds of jobs kept me learning new things and figuring out how to explain them to other people. That’s one of the things I most love about writing: I’m constantly learning new things. Your Martin Preuss series is set in Ferndale, Michigan. How important is setting to your stories, and what made you choose Ferndale?

I chose Ferndale mostly as a matter of convenience: I live there. When I want to scout locations, I can just walk around to soak up the sights and sounds. I like to say that people can walk around with any of my books in their hands and see where the locations are. There’s also another reason why I chose Ferndale: one of my favorite writers is Henning Mankell, who set his mystery series in Ystad, a small city in Sweden. As it happens, Ferndale is almost exactly the same size as Ystad, so I feel like I’m making an homage to Mankell by giving my detective a beat similar to Mankell’s Wallander. What goes into creating a fictional character for a series? Are there any differences with creating a main character for a stand-alone novel?

So when I started the first Preuss novel, I had planned (or hoped, I should say) that it would be part of a continuing series. As I’ve written the books, Preuss has sort of unfolded himself to me as a character, and I’ve gotten to know him better and better—and my readers have, too. Another important aspect of writing the Preuss series for me and my readers is Preuss’s son, Toby. Toby is multiply handicapped and lives in a group home, but he is an integral part of Preuss’s life. Indeed, the relationship between Toby and his father is, in my humble opinion, at the heart of the series. Martin Preuss loves his son fiercely and cares for him with great tenderness, and Toby returns the love unconditionally. One reviewer called their relationship “a touching element that’s a constant in the series”; another reviewer noted, “The complexity of the main character and especially his deep love for his handicapped son draw the reader into the story in a way that few other mysteries do.” Toby has profound physical and cognitive disabilities, but the character is sweet, loving, joyful, and everybody’s favorite character in the books. (Also one of the few rounded, sympathetic portraits of handicapped characters I’ve seen.) Toby is based on my own grandson Jamie, who sadly passed away a few years ago; writing him as a continuing character in this continuing series gives me a chance to keep that wonderful young man alive for me and everyone who knew him. What would you like HeartWood readers to know about your mystery series and especially the soon-to-be-released In the House of Night?

Each book uses its crimes as a starting point for examining larger crimes and more significant social issues. The latest book, In the House of Night, perhaps most overtly deals with contemporary social and political concerns. The book emerged from my growing concern with the spread of white nationalism in this country. Set in 2013, the book looks at how the white nationalist movement began to edge into the mainstream of American culture. Here's the story: When the police investigation into the murder of a retired history professor stalls, friends of the dead man plead with PI Martin Preuss to find out what happened. The twisting trail leads him across metropolitan Detroit, from a peace fellowship center, a Buddhist temple, and a sprawling homeless encampment into a treacherous world of long-buried family secrets where the anguished relations between parents and children clash with the gathering storm of white supremacist terrorism. You typically divide your time between Michigan and Florida. Do your writing habits and routines change with a change of location?

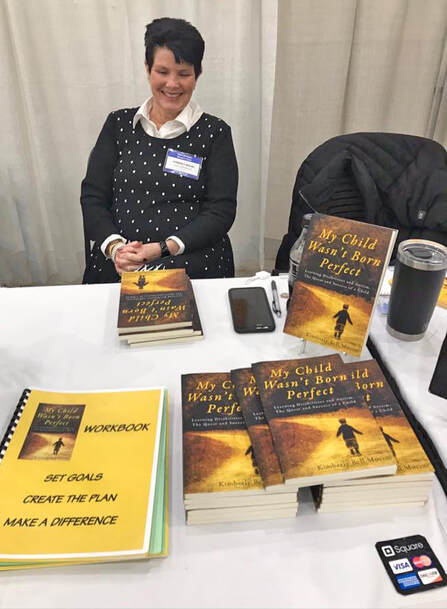

Have you found it harder or easier to write during the COVID-19 pandemic? How has COVID-19 affected the way you interact with readers? As I mentioned in the last question, the pandemic quarantine made me rearrange my writing schedule a bit. And it’s played havoc in connecting with readers in books fairs and exhibits . . . they’ve all been cancelled this year. It’s made me rethink how I connect with readers. I always hold book launch parties for each new book with music, refreshments, readings, and so on. This year, out of concern for bringing people together, I’m organizing a virtual book launch for In the House of Night. It’ll be on my Facebook page (and Youtube, if I can figure out how to do it) on Tuesday, October 6, from 7 till 8 p.m. All writers have to deal with discouragement and doubt at times. How have you dealt with those negative emotions?

This writing life must not be for me, I decided. I’m just not good enough. Don’t have what it takes. So I gave up writing fiction. It was painful, even devastating. I had failed at the one thing I had wanted to do since I was little. But I still thought I had some chops as a writer, just not a fiction writer; I had already had several writing jobs, as I mentioned previously. I turned away from literature entirely; I turned away from reading. Instead I became the professional writer I described in my response to your first question. And I did well in that world. It came to pass that the writing I was doing for others relit that little holy pilot light. I started thinking about returning to fiction, and about writing under my own name. About the importance of stories in our lives. About the need to do it. In the gap between my fleeing from imaginative writing and returning to it—a ten year gap—I grappled with what success as a writer really meant, and more importantly what it wasn’t. I met editors, and became an editor myself, and realized how capricious and unpredictable the process really is. With the confidence I had gained, and with what I had learned about writing, I came through that decade of despair by learning that the writing itself and the changed qualities of mind and heart that accompany writing really are more important than the approval suggested by acceptance by others. As if that insight broke some self-imposed spell, in the years since I’ve published eight novels (seven in the Martin Preuss mystery series), two novellas, two books of poetry, a handful of stories, and dozens of poems in print and online journals. That voice shouting in your ear, the voice a friend of mine personifies as “Sid”—Self-Inflicted Doubts—never goes away. But with practice and wisdom, you can silence it long enough to get some good work done. And in the end, that’s really all that matters. Anything else you’d like to add? Many thanks for some great questions! I appreciate the opportunity to appear here. Find Donald Levin and his work here:

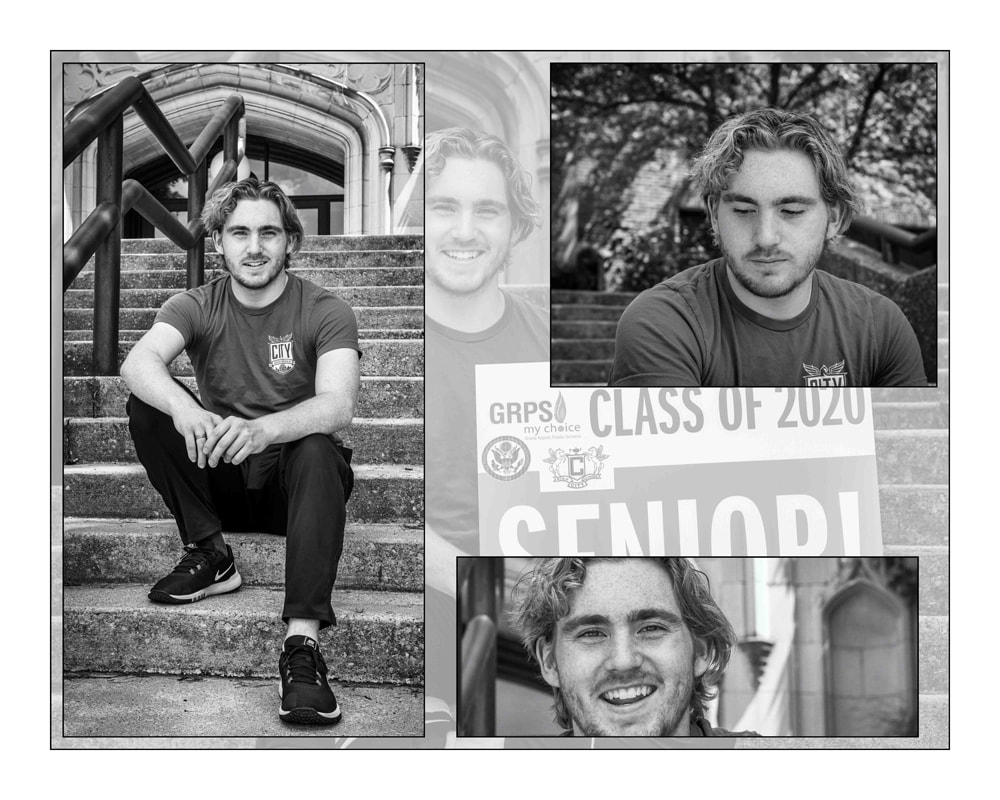

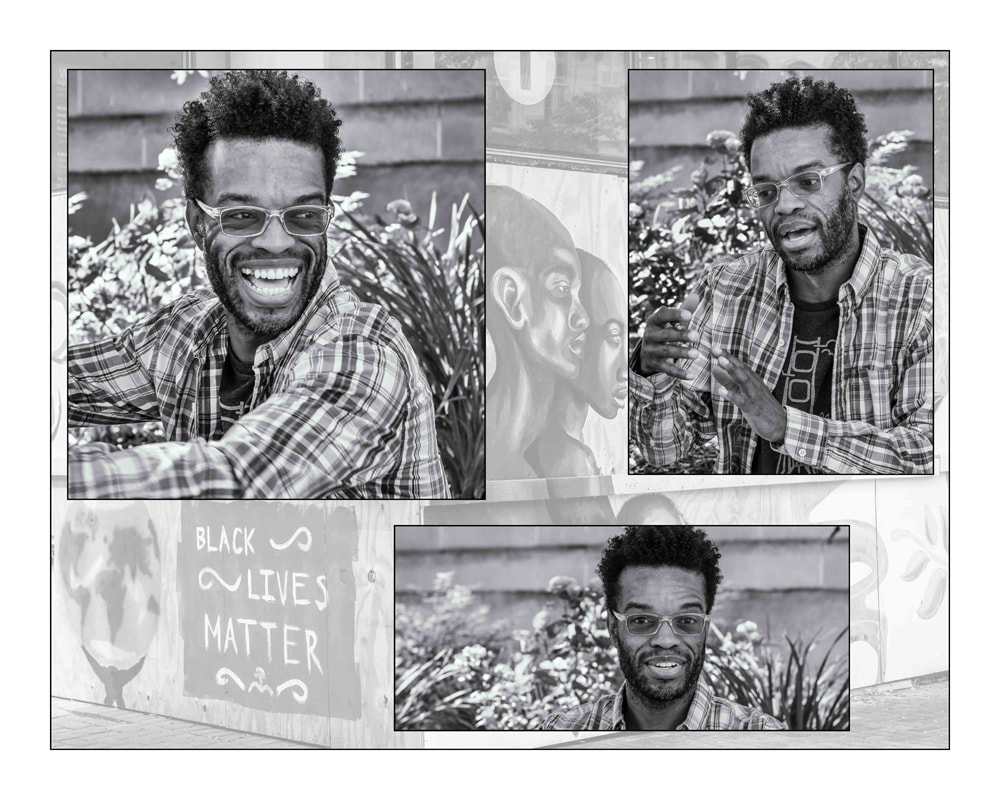

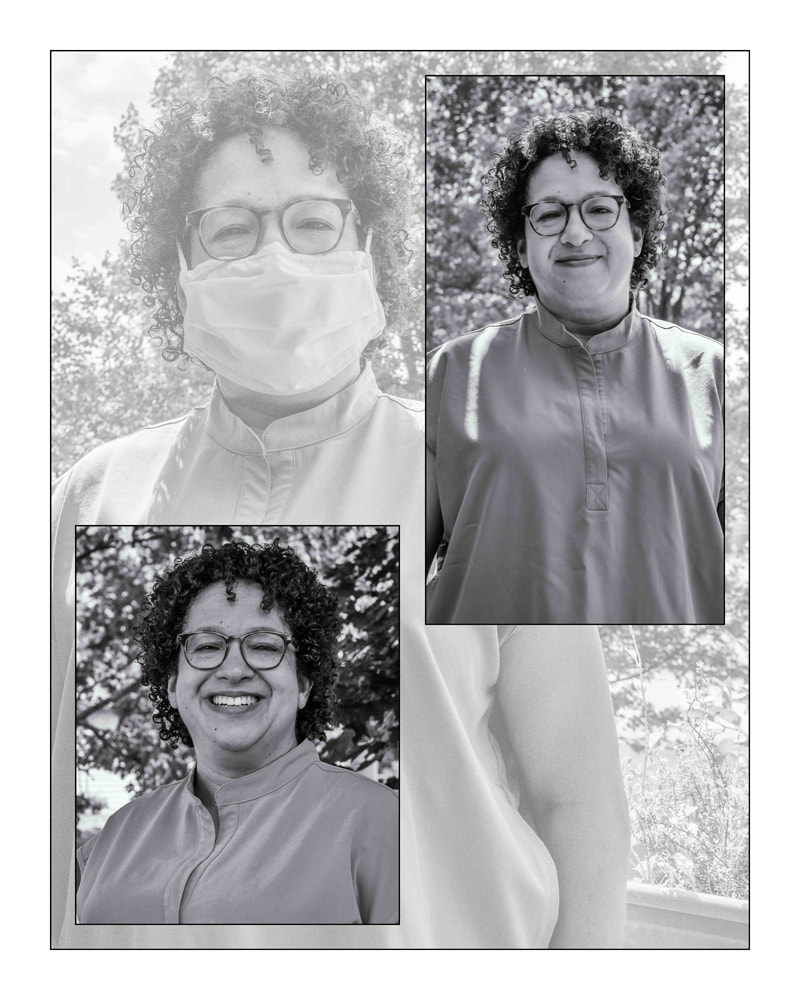

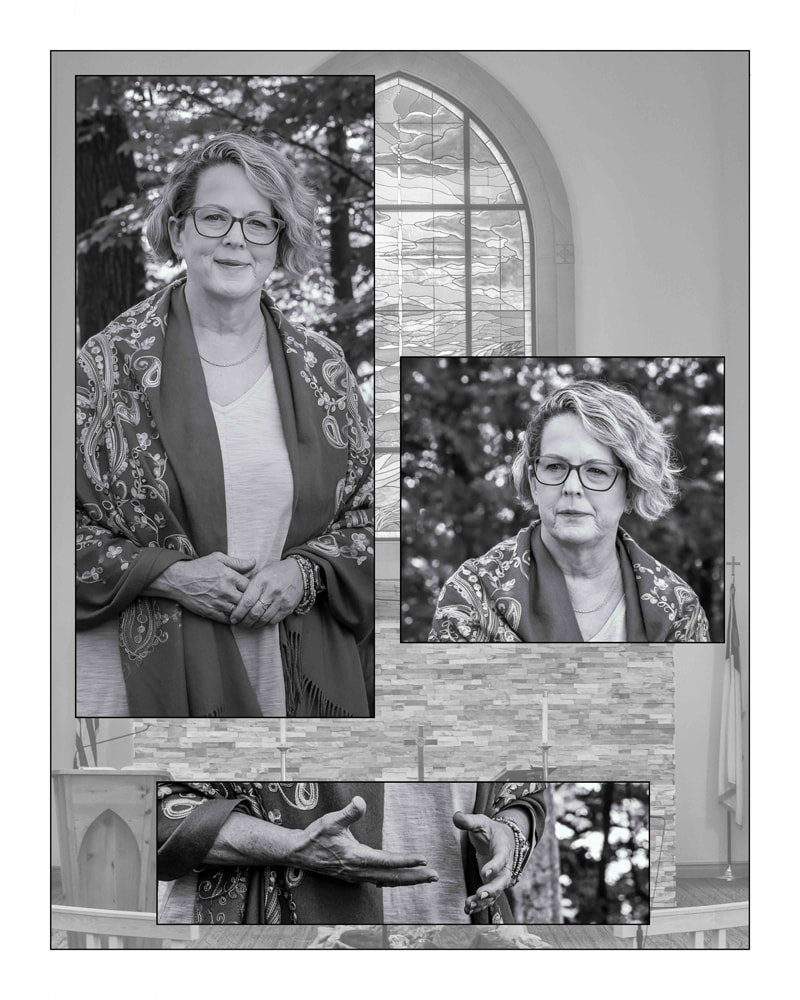

Website: www.donaldlevin.com Blog: www.donaldlevin.wordpress.com Amazon author page: https://amzn.to/32y8bLw Twitter: @donald_levin Instagram: Donald_levin_author Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Donald-Levin-Author-121197194659672 These challenging times can be both stimulating and stifling to creative types. Some writers and artists I know have found comfort in their work; others have been unable to summon their muses and have turned to other activities for solace. I say, whatever works! These times are exceptional, and as I recently read in an article a friend sent me, “During this extraordinary time, we have to realize that everyone now has an additional part-time job that might be called Citizen of the Covid-19 Pandemic,” and we need to give ourselves credit for the time and energy that extra work takes.  Gail Howarth Gail Howarth One artist who's managed to do inspired and inspiring creative work while coping with the pandemic is photographer Gail Howarth. Regular readers of HeartWood may remember seeing Gail featured here a couple of years ago. At that time, she was working on a photography/writing project with Mel Trotter Ministries, a Grand Rapids nonprofit organization that works with homeless people. Now, she is once again combining photography and writing to call attention to today's pressing issues, which include but are not limited to COVID-19, essential workers, race and racism, and LGBTQIA community concerns. What led you to undertake this project? City Center Arts in Muskegon offered me the opportunity to be the featured artist there from September 1 to October 10. The gallery has been very supportive of me, my nature and landscape photography, as well as another project I am working on called The Gratitude Project By Lakehouse Photo. Originally we were going to feature The Gratitude Project. However, the rest of the exhibit will honor essential workers. We felt that gratitude, while a worthy topic, might seem insensitive to those that have sacrificed so much. We thought about postponing the featured artist wall or displaying my landscapes. But I felt like we were missing the opportunity to do something meaningful. The year 2020 has been challenging. The pandemic, racial tension and rioting, and a divide that grows deeper daily in our nation weigh heavily on my heart. I just kept thinking, this is a time to heal, not to fight amongst one another. When I proposed A Time To Heal to the folks at City Center Arts, they quickly agreed to the project. Christina once asked herself, Am I Black Enough? Later in life, as she experienced racism in many forms, the answer became clear. Christina expresses her concerns, her anger, and her wisdom by blogging and through dance. How did you find people to participate? Were most readily willing, or did you have to persuade some? I asked everyone I knew if they would participate, and then they asked everyone they knew. I posted requests for participants on my Facebook and Instagram pages and even contacted local social justice organizations. Most of the participants were referred through the gallery or Facebook friends. Of the 17 participants, I knew less than one-third personally. I received a lot of non-responses to emails and phone calls. However, those that expressed an interest in the project showed no hesitation about participating. Everyone felt like it was an important project and wanted to be involved. Like so many others 2020 grads, Chauncey lost the opportunity to complete his senior year of high school in person and to experience senior prom, skip-day, an actual graduation ceremony, and more. Read more about Chauncey here. How do you think communicating these varied stories and images can promote healing, both for individuals and for our country and world? In a nutshell, we need to get to know one another. The project gives folks from various backgrounds the opportunity to share their journey with people that are generally not a part of their community. Once we find common ground, it will become easier to communicate about and resolve tough issues. One example from the project would be that there has been immeasurable conflict related to wearing a mask to keep COVID-19 from spreading. There are many reasons stated, but I believe the biggest factor is that folks don’t know anyone that has had it, and therefore, it does not seem real. Three of the participants of the project have had COVID-19. Though all three have recovered, they struggle with ongoing health issues. One person caught the virus from a man that did not survive. Another worked in one of the hardest-hit hospitals in the Detroit area. She witnessed countless deaths every day. All three encourage everyone to wear a mask. Once you know someone that has had the virus, you will likely not question whether mask-wearing is right or wrong. Healing begins one person at a time. Hopefully, healing begins with one person, then a second and a third, and multiplies and impacts a whole community, a state, a nation, and beyond. Healing can be hard work and take years. But it can also be quite magical. Have you ever had a rigid belief about a thing and then learn one new fact about it, and it shreds everything you ever believed? I do hope that folks will find a few magical moments from the exhibit and blog posts. I don’t believe my project alone can make a profound change in the world. I do think that projects with the same or similar intentions are popping up all over as a reaction to the dysfunction we are currently experiencing. I hope that collectively change can and will happen. Lastly, I will admit that there was a moment during the early part of the project that I became disillusioned. Not all of my friends or family felt the project had merit. They thought that the result might create greater divisiveness versus the desired outcome of healing. I shared with one of the participants that my heart was a bit broken by the response. I asked her earnestly, what if the only heart opened or healed was my own. Her response was: Well, then the whole project is worth it. I am grateful, and I cherish her words. Working as a respiratory therapist at one of the hospitals hardest hit during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cindy contracted COVID-19. Now recovering, she asks that everyone wear a mask. In the introduction to “A Time to Heal” on your blog, you write about parallels between the present day and the 1960s. What similarities and differences do you see between the two times? Now and then, social unrest led to demonstrations and rioting. In the ’60s, the issues were related to civil rights, the feminist movement, the Viet Nam War, and the gay liberation movement. Today, we face the same problems and more, but the war we are fighting is with one another. Also, in the ’60s, people still had faith in our government, that our voices would be heard, and that real change could happen. Today, we have lost faith in leadership and our government, that our voices, no matter how loudly we cry, fall on deaf ears, and there is little hope for change. Kwame uses his sense of humor and insight to elevate awareness related to racism and the Black Lives Matter Movement. Kwame believes we are fundamentally bound together and that together we must find a way to get along. In your interviews with this broad spectrum of people, have any common themes emerged? The commonality would be the need or desire of the participant to tell their story or to be heard. All felt that in doing so that it might, in some small way, make a difference. Susan Bishop, MD, is a pediatric doctor. As COVID-19 has significantly changed patient care, she misses children's hugs and unmasked smiles. In an email, you wrote, “The creative process is funny for me. I never have a clear picture of what something will be in the beginning. It just morphs into what it becomes.” In what ways was that true for this project? First, I had no idea if I could pull off this project. I had two months during a pandemic to find people willing to be photographed, to share their stories, and translate them into an exhibit of words and images. Initially, I thought I would display one photograph and a few keywords of each person to convey the story. However, I could not come up with a smart way to show the words. In the end, I decided to label the images more traditionally. Each piece has a name and just a little information about the participant. Hopefully, viewers will become curious enough to read more about the participants on my blog. Then, as I selected and edited photos, I realized that for most participants, a single image left the story incomplete. I began mounting three to five images into a template with a plain white background. The stories were coming together, but still, something was lacking. One day, I accidentally placed one of the photos behind the others. It was fabulous!! I reduced the grayscale of the background image (made it lighter), and it became part of the story. In some cases, I had to backtrack to find and photograph backdrops that would complete the story. Lastly, I initially had a narrow concept of who should participate. The expansion happened naturally and felt right. When Justin learned personal protection equipment was in short supply, he came up with a plan that included renting the second largest cargo plane in the world and having it flown to China, filled with supplies, and flown back to Ohio to begin distribution. He then purchased US-made mask-making equipment and started production in Ohio. How has this project affected you personally? Deeply and on so many levels. There were many days that I felt hopeless. The division between people feels as if it grows larger every day, and I did not feel as though I was working fast enough or hard enough. But I came to believe that I am doing what I can to be a positive force for awareness and change. I will, in some way, continue the work that has begun with this project. I am honored and humbled that complete strangers would take the time to share their life experiences with me. Their words forever change me. The most life-changing aspect of the project is related to racism. I have never considered myself a racist. But, I have become more aware of the cultural bias that I carry with me. I listen with new eyes and ears, and feel with a heart more open. And, as those old untruths pop up, I look them over and toss them away. We have so very much to learn from one another. I am a forever student, and can barely wait for my next teacher. Siena is working toward awareness and social change as a member of the Sunrise Movement, an organization that seeks to remove oppressive and unsustainable systems to create a just future. What is your hope for this project and its impact? I hope that hearts and minds will be changed, that we will become a more unified people, even if we disagree, and as a result, create a better future for our children. That is a pretty big hope, isn’t it! I am not sure if it is realistic at all. But, in the words of John Lennon, “You may say I'm a dreamer, but I am not the only one.” I hope others will be inspired to start projects that promote healing and unity. Pastor Sarah believes it is time to put an end to our differences based upon race, learn to imitate the Kingdom of Heaven, and to live as one. Read more about Pastor Sarah here. A Time To Heal will be on display at City Center Arts from September 1, 2020, until October 10, 2020. Hours are limited, so please check the website before traveling to the gallery. Blog posts related to the participants are located at https://lakehousecc.com/living-at-the-lakehouse/

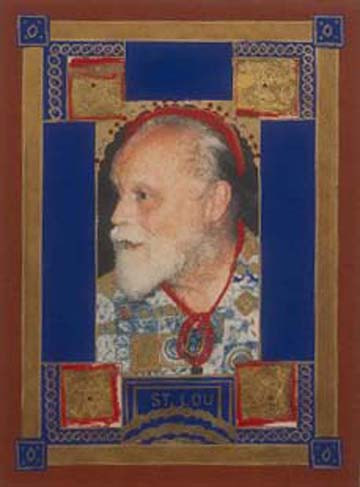

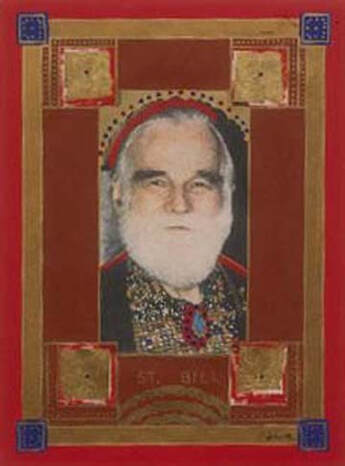

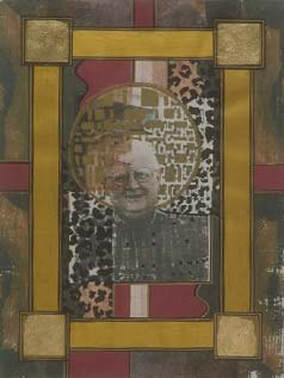

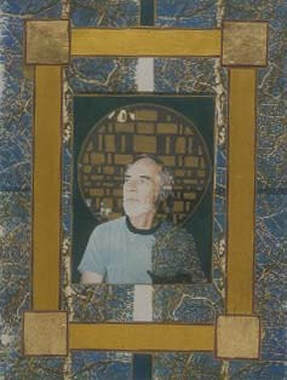

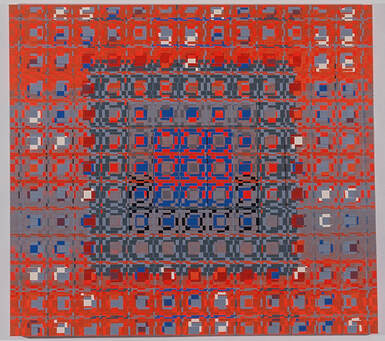

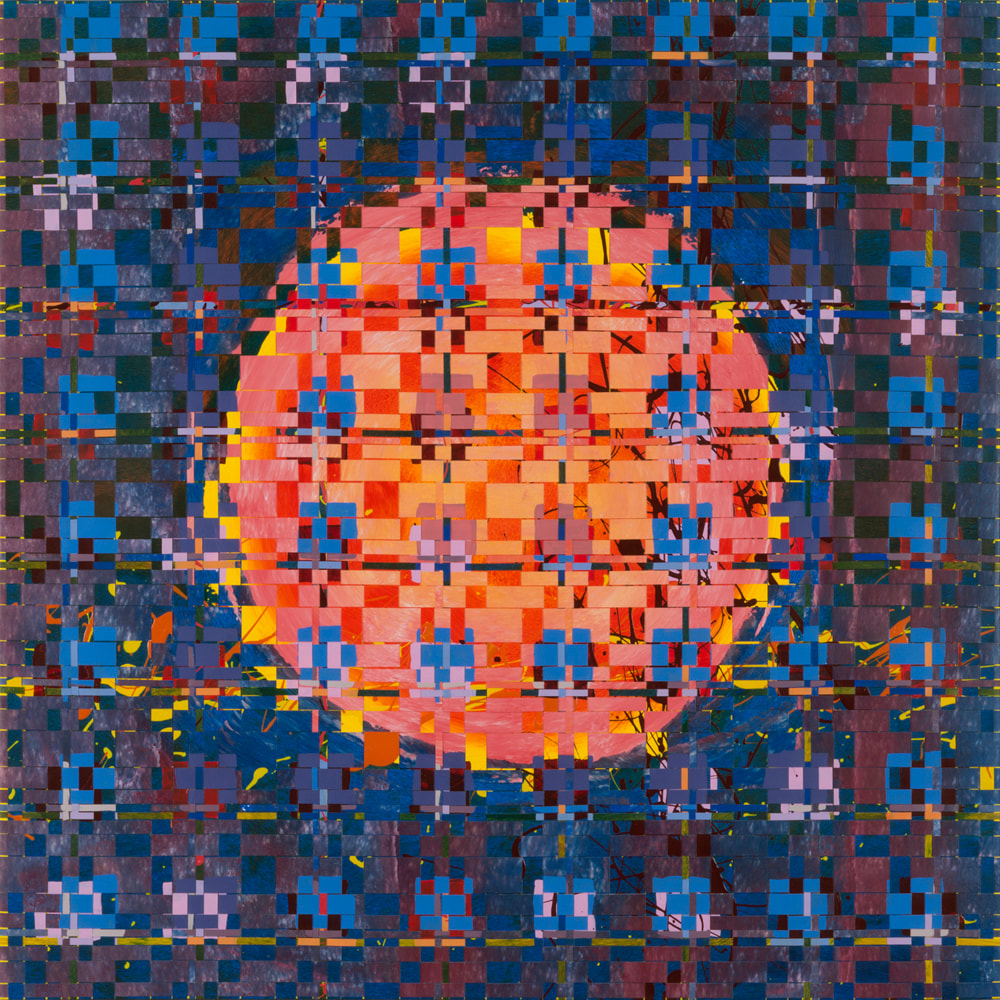

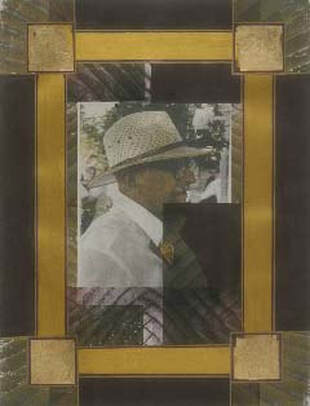

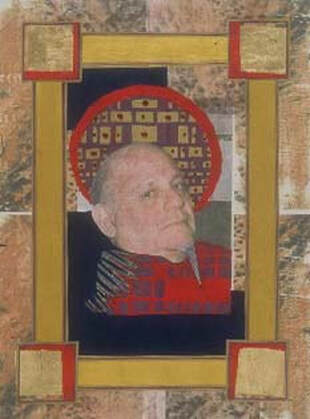

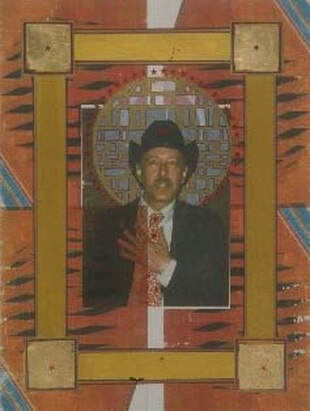

Not all blog posts related to the project are complete. Consider subscribing to be notified of new posts. The last installment of HeartWood—the story of a young writer’s devotion to his grandmother and her literary legacy—got me thinking about other stories of art and devotion, which took me back to a trip to Albuquerque three years ago.  Mosaic in Albuquerque's Old Town Mosaic in Albuquerque's Old Town Albuquerque, nearby Santa Fe, and their surroundings are spilling over with creative people whose devotion to their art is evident. Painters, sculptors, mosaic artists, multi-media creators, jewelry designers—they're everywhere, and so are the fruits of their talents.  Promoting the Santero Market Promoting the Santero Market Evident, too, are signs of a different kind of devotion: works of art inspired by spirituality and religious faith. I learned about one type of this art from two women I chanced to meet on a Sunday morning in Albuquerque's Old Town. Felis Armijo and Ramona Garcia-Lovato were sitting at a table in front of San Felipe de Neri Church, signing up volunteers to help with the upcoming Santero Market. Santeros (and santeras) are artisans who craft religious icons called santos. Originally created for churches, these statuettes of saints, angels, Mary and Jesus, usually carved from wood and often decorated with home-made pigments, are now sold to tourists.  My conversation with Felis and Ramona rambled from topic to topic, touching not only on art, but also on writing, life stories, geography, and human nature. From their curiosity and warmth, it was clear these two women were dedicated not just to the event they were promoting and the parish to which they belonged, but also to connecting with other people—an art in itself.  Petroglyph Petroglyph After our time in Old Town, Ray and I ventured out to Petroglyph National Monument, a short drive away. One of the largest petroglyph sites in North America, the monument features designs and symbols carved onto the surfaces of volcanic rocks by indigenous people and Spanish settlers 400 to 700 years ago. The site and its images still hold spiritual significance for the descendants of both groups of people.  Significant symbols Significant symbols The meanings of some symbols have been lost over the centuries; others are known by a few indigenous groups, but it is considered culturally insensitive to reveal the meaning of an image to others. For me, it's enough to know that the symbols meant something to the people who created them and to ponder the combination of location and inspiration that gave rise to their work.  Larry Schulte Larry Schulte Not all works of devotion have religious significance. They also can be inspired by a more secular kind of admiration. Case in point: my friend Larry Schulte, an artist who now lives in Albuquerque, created his own "Saints" series, featuring mortals who have made a difference in his life. “I was raised in a fairly strict Roman Catholic home, and I left that faith many years ago—mostly because of their stance on gay people, that we were sinful,” Larry reflects. “These saints in some way replace the saints I learned about in my childhood . . . They are all loving, sharing people who have made my world a better place. We all need something to believe in. For me it is love, art/creating, and people, rather than any organized religion.”  St. Lou St. Lou Some of the fifteen mixed media pieces, which Larry created at the Ragdale Foundation, an artist's colony north of Chicago, feature well-known figures—such as the innovative composer Lou Harrison and Harrison's life partner Bill Colvig, an instrument builder who collaborated with Harrison on gamelans and other percussion instruments. But they also include more personal choices: Larry’s undergraduate art instructors, St. Jack and St. Keith, for instance. “Jack was particularly influential in my pursuing art,” Larry recalls.  St. Elvira St. Elvira St. Elvira’s son Peter was Larry’s roommate and best friend during their days at the University of Kansas in the late 1970s to early 1980s. Elvira lived in New Jersey but had visited Peter and Larry in Kansas. “After I moved to New York City, she included me in holiday family gatherings when I wasn't able to get back to my own family in Nebraska. She adopted me as another son.”  St. Bill St. Bill In 2016, Larry and his partner Alan Zimmerman, a percussionist, traveled to San Francisco for a concert of Harrison's music to celebrate what would have been his 100th birthday. Two of Larry's art works (St. Lou and St. Bill) were exhibited at the concert, which was sponsored by the non-profit organization Other Minds.

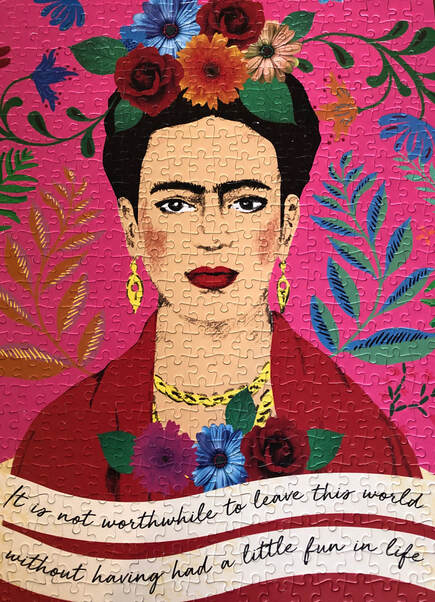

Jigsaw puzzles: among the new ways of entertaining ourselves Jigsaw puzzles: among the new ways of entertaining ourselves In recent months, we’ve all had to adapt in ways we never expected: new ways of shopping, socializing, working, entertaining ourselves (jigsaw puzzles, anyone?). With Ray and me both retired, the changes weren’t as drastic for us as for many people. While there have been challenges, our adjustment has been relatively smooth, for which I’m grateful. But this home-centered span of time has also shown me how un-adaptable I am in other parts of my life and how I’ve been holding onto expectations that don’t square with reality.  Take my activity patterns, for example. For most of my life, I was an early riser. During my working years, both as an employee and as a freelancer, I usually got up at 5 a.m. and started work at 7:30 or 8:00. For a while after I retired I continued waking up and getting out of bed by 5:00 or 6:00, whether I wanted to or not. I seemed to be hard-wired to get up and get going early. In the past year or so, though, I’ve started sleeping till 7:00, 7:30, and sometimes even later. I feel like I need the sleep, like my body demands it, especially if I’ve done something intensely physical the day before, like a long hike or hours of outdoor work.  I am not a slug! (Photo: Peter Stevens) I am not a slug! (Photo: Peter Stevens) Yet every time I get up later than 6:00, I scold myself for being such a slug, and I still try to keep to a routine that’s based on getting up earlier: meditating and doing yoga before breakfast, then making and eating breakfast, doing some reading over breakfast, cleaning up my dishes and myself, getting dressed, making the bed, doing whatever else needs doing, like taking out the mail, and still being ready to start the day’s main activities (writing and book promotion in the morning; chores, errands, and recreation in the afternoon) by 8:30 or so. So every day starts with this ridiculous and totally unnecessary tension about keeping to a ridiculous and totally unrealistic schedule.  Yoga: First thing in the morning? Or not. Yoga: First thing in the morning? Or not. I’ve experimented with various alternatives—putting off yoga until later in the day, meditating before bed instead of first thing in the morning, streamlining this or that. But I’m starting to see the problem isn’t with the routines themselves, it’s with my attitude toward them. So what if some mornings I get a late start and only have time to write for half an hour instead of an hour or two? Maybe I’ll make up for it another day. And if not, so what? Yes, I feel better on days when I write and I feel off-kilter when I don’t—writing is my happy pill, after all. And yes, I get great satisfaction from seeing the word count and page count increase by the day. But if the world comes to an end, I doubt it will be because I wrote 100 words today instead of 1,000.  Ahhh, the luxury Ahhh, the luxury My reality has shifted, and it’s high time to adapt to the new one instead of clinging to the old one. The truth is, I’ll probably never again routinely get up at 5:00. So why not try to see my sleeping-later habit for what it is—a response to a physical need, not a sign of sloth--and just enjoy the luxury of being able to structure my days around it. Which brings me to another realization about reality. Structure is something else I sometimes feel conflicted about. As I wrote in a 2016 blog post, we all have our own tolerance levels for chaos and structure, and finding the right balance between them is crucial for creativity.  Structure provides a bit of certainty in uncertain times Structure provides a bit of certainty in uncertain times As I’ve been examining how to adjust my usual routines to my unpredictable sleep patterns, I’ve questioned whether I still need a routine at all. After all, I’m retired. Most of the things on my to-do list are want-to-dos, not have-to-dos. Why not just do what I feel like when I feel like it? I’ve thought a lot about that lately, and I’ve come to this conclusion: There may be a time to ditch my routines, but this isn’t it. Experts say having consistent daily and weekly routines gives us a sense of certainty in these uncertain times. The trick is to make your days consistent, with enough variety to keep boredom at bay. Sounds like exactly what I’m aiming for as I try to adapt to new realities. I’ll let you know how that works out.

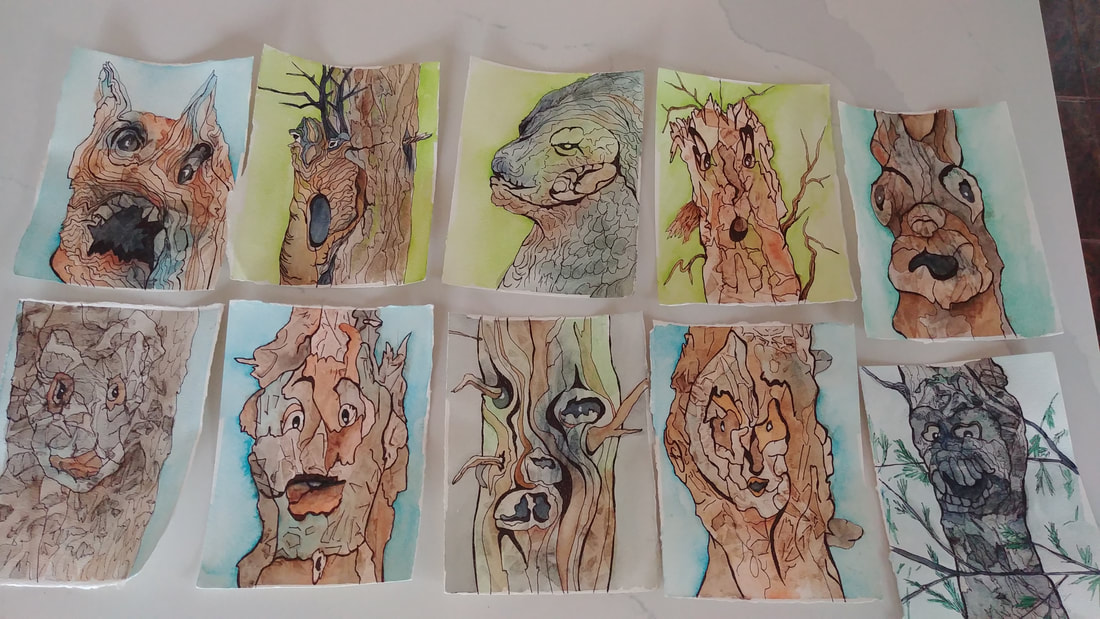

Have you adapted in any surprising ways over the past months? Have you discovered aspects of your life you can let go of and others you still need to hold onto? In the last installment of HeartWood, I wrote about some of the ways I've been filling my unexpected free time during the weeks of social distancing and Stay Home - Stay Safe. In this installment, I'm giving other folks a chance to share what they've been doing. And what a variety of things they've come up with! Check them out! Tonya Howe |

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

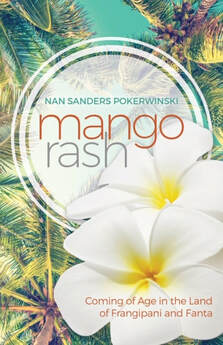

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed