|

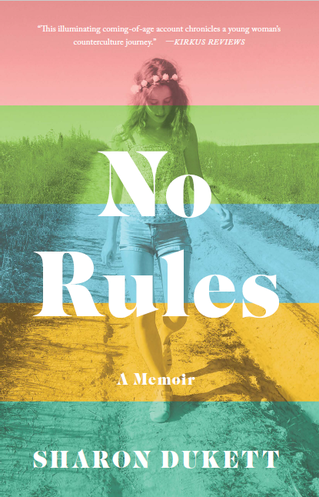

With in-person author events still on hold indefinitely, I'm devoting one blog post each month to an author interview. This month's interview is with Sharon Dukett, author of the memoir No Rules. Desperate to escape the stultifying life she saw ahead for herself in the early 1970s, and entranced by the California hippie scene, Sharon ran away from home at sixteen. No Rules details her precarious journey through the counterculture, an experience that would mold her into the strong woman she became. Every teenager who ever lived probably fantasized about running away from home and living on their own, but most of us lacked the courage and motivation to pull it off. What do you think made the difference for you?  Sharon in 1970 Sharon in 1970 I was miserable with the prospect of what was ahead for me if I didn’t go. My mother seemed so unhappy, as did my older sister. Leaving wasn’t just for me. It was as though I was breaking out for them, too, demonstrating it was possible to live a different life. Plus I had my older sister with me when I left, which made me feel protected. The catalyst for that leap was being dumped by my first real boyfriend, which left me feeling empty and hopeless. It took a different kind of courage to decide to share your story—a story that you had kept to yourself for a long time. What gave you that courage? As I read writers like Mary Karr and Cheryl Strayed, I saw that what made their books shine was the honesty. They had great stories, and I knew I had a good story, too. But it would be empty if I didn’t share my deepest thoughts and feelings, good or bad. My success and sense of accomplishment in my career and my personal life as I grew older made me strong enough to share my story regardless of others' reactions. In the Epilogue, you mention that you began writing as a way of healing from unresolved hurts. At what point did the book transition from personal writing to something you wanted to share with others?  It quickly transitioned as I got caught up in the memories of the times. I had always wanted to write a book, but when I was younger I never knew what to write about. Once I began writing about this, I didn’t want to stop. But until I had a personal computer, the idea of using a typewriter was overwhelming. If the personal computer had not been invented, I would have never been able to complete a book. In No Rules, you write honestly about some difficult subjects. What parts of the book were most challenging to write? I found one of the most challenging subjects was writing about falling in love with someone that I later came to despise and recognize as a con artist. I had to recapture the naïve innocence I felt at the time and block out what I knew would come later. It was difficult remembering being attracted to him as he later repulsed me. Were there parts you especially enjoyed writing?  Hitching across Canada Hitching across Canada There were some parts that just flowed out of me like they were already written, and I was just the conduit putting the words on paper. I cried through writing the scene with Cindy after she finds Jesus. And the trip across Canada could have been an entire book alone. It was much longer in the original draft. Reliving those memories were like re-experiencing the trip. What helped you access the memories that form the basis of No Rules?  Venice Beach Venice Beach Because this was such a momentous time of my life, much of this was deeply ingrained in my memory. I even believe I recall some exact dialog. I did write the entire first draft in the 1990’s when it was all fresher in my mind. I have some photographs from the time that I used for reference. For example, I have a group shot of those on the ride from Patterson, NJ to Ohio, and photos of our room at the A-House in Provincetown. I also found the more I wrote, the more the memories would overtake me. When you are writing memoir, you take up residence in that time and place and the images and experiences flood back at you. I also played music I listened to during that era, particularly if it was music I don’t often hear. I loved what you wrote in the Epilogue about the people from that time in your life being your “first tribe.” How did they function in that role?  Yurt building Yurt building Despite some of the bad things that happened, we were all part of a larger community. No matter where you went, you could easily connect with others because they looked like you. I learned so much from all these people because our backgrounds were highly diverse. It didn’t matter what socio-economic, ethnic or religious background you came from—no one cared, and no one typically asked. I don’t think that has ever happened in America before or since. You can’t live through a time like that and not recognize the common humanity in all of us. Once you’ve seen it, you can’t un-see it. In the acknowledgments you say the book is an accumulation of years of work. Take us through your journey from initial idea to publication. How long did you spend writing and revising the book? What avenues did you explore in pursuing publication? How did you come to be published by She Writes Press?

You also mention that you belonged to a writer’s group. What did you find valuable about that experience? Were there any challenges?  Sharon with Ernie, 1972 Sharon with Ernie, 1972 I spent several years in the writers group. I don’t think I was always open to the input from some of the members, probably because of how it was presented. But generally speaking, even those that came across as being overly critical had truth I could learn from. In time we modified our process for critique so we had to start out with three or more positive comments first before any negative comments. This was better for all of us because writers need positive reinforcement of what works along with knowing what to improve. It was fairly time consuming as there were four or five of us turning in lengthy chapters for review every two weeks. I know my chapters tended to be 7,000 or 8,000 words each. They were all cut a lot when I revised later on. I stayed in that group until I put the work aside in 2000. What do you hope readers will take away from No Rules?  Sharon with her older sister Anne Sharon with her older sister Anne I want readers to experience what it was like to live in those times, and the transformation that came about as a result of discovering feminism and growing my own strength. What did you gain by writing the book? By writing this book, I have completed a goal I had for years, and often wondered if I would ever reach. By doing so, I was able to preserve a unique time in history that no longer exists and will always be part of who I am. What’s next for you as an author? I am currently working on a thriller novel that takes place in the near future when climate science has been declared to be illegal propaganda in the US, and activists are detained and disappear. Anything else you’d like to add? One of the greatest experiences of being a writer that I never expected, particularly now because of social media, are the wonderful writers I have met and connected with online. My new tribe is made up of writers who are supportive of one another and offer support and information. We inspire each other and help one another reach our goals. I have discovered I am once again part of a larger community.

8 Comments

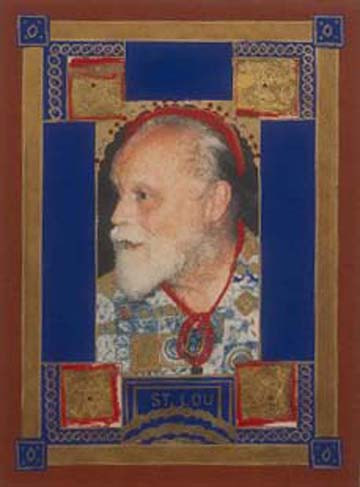

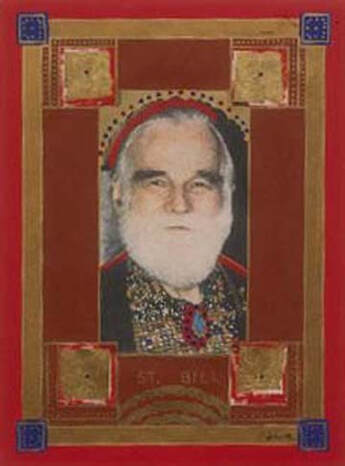

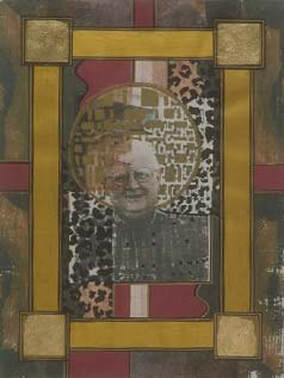

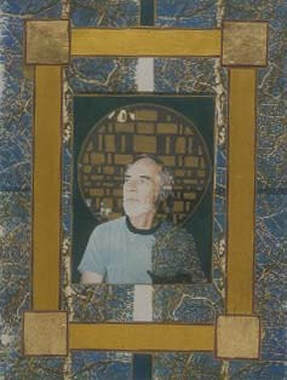

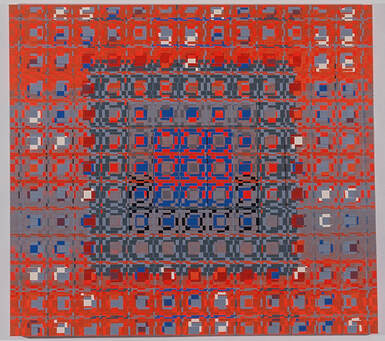

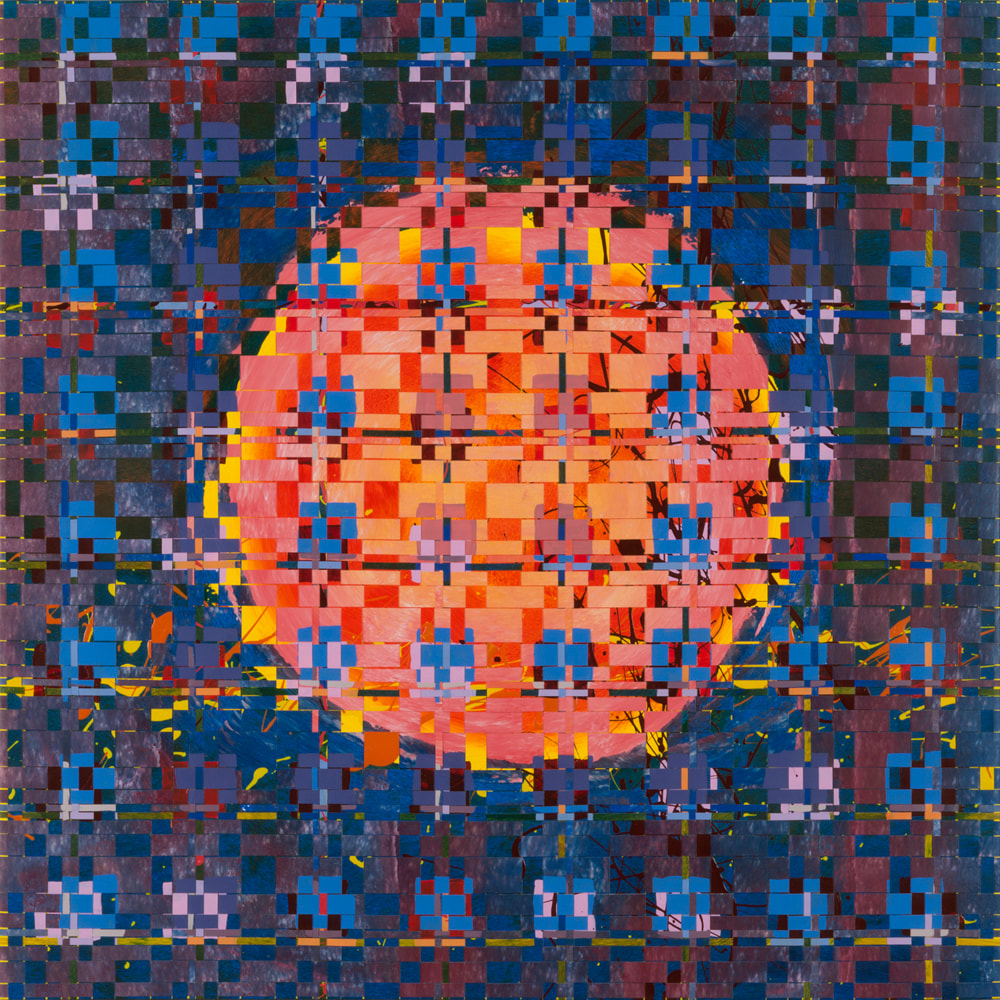

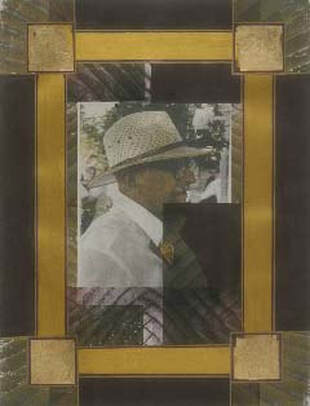

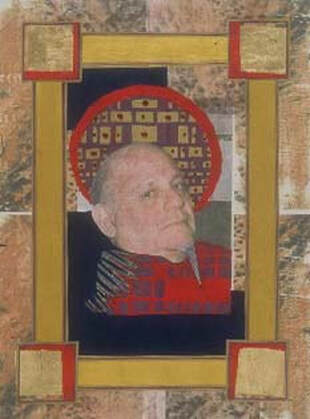

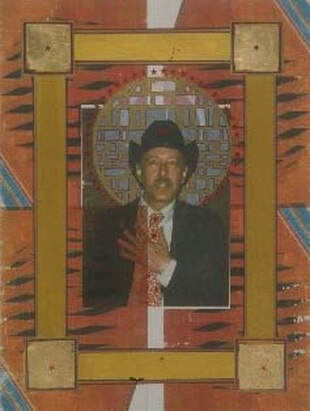

The last installment of HeartWood—the story of a young writer’s devotion to his grandmother and her literary legacy—got me thinking about other stories of art and devotion, which took me back to a trip to Albuquerque three years ago.  Mosaic in Albuquerque's Old Town Mosaic in Albuquerque's Old Town Albuquerque, nearby Santa Fe, and their surroundings are spilling over with creative people whose devotion to their art is evident. Painters, sculptors, mosaic artists, multi-media creators, jewelry designers—they're everywhere, and so are the fruits of their talents.  Promoting the Santero Market Promoting the Santero Market Evident, too, are signs of a different kind of devotion: works of art inspired by spirituality and religious faith. I learned about one type of this art from two women I chanced to meet on a Sunday morning in Albuquerque's Old Town. Felis Armijo and Ramona Garcia-Lovato were sitting at a table in front of San Felipe de Neri Church, signing up volunteers to help with the upcoming Santero Market. Santeros (and santeras) are artisans who craft religious icons called santos. Originally created for churches, these statuettes of saints, angels, Mary and Jesus, usually carved from wood and often decorated with home-made pigments, are now sold to tourists.  My conversation with Felis and Ramona rambled from topic to topic, touching not only on art, but also on writing, life stories, geography, and human nature. From their curiosity and warmth, it was clear these two women were dedicated not just to the event they were promoting and the parish to which they belonged, but also to connecting with other people—an art in itself.  Petroglyph Petroglyph After our time in Old Town, Ray and I ventured out to Petroglyph National Monument, a short drive away. One of the largest petroglyph sites in North America, the monument features designs and symbols carved onto the surfaces of volcanic rocks by indigenous people and Spanish settlers 400 to 700 years ago. The site and its images still hold spiritual significance for the descendants of both groups of people.  Significant symbols Significant symbols The meanings of some symbols have been lost over the centuries; others are known by a few indigenous groups, but it is considered culturally insensitive to reveal the meaning of an image to others. For me, it's enough to know that the symbols meant something to the people who created them and to ponder the combination of location and inspiration that gave rise to their work.  Larry Schulte Larry Schulte Not all works of devotion have religious significance. They also can be inspired by a more secular kind of admiration. Case in point: my friend Larry Schulte, an artist who now lives in Albuquerque, created his own "Saints" series, featuring mortals who have made a difference in his life. “I was raised in a fairly strict Roman Catholic home, and I left that faith many years ago—mostly because of their stance on gay people, that we were sinful,” Larry reflects. “These saints in some way replace the saints I learned about in my childhood . . . They are all loving, sharing people who have made my world a better place. We all need something to believe in. For me it is love, art/creating, and people, rather than any organized religion.”  St. Lou St. Lou Some of the fifteen mixed media pieces, which Larry created at the Ragdale Foundation, an artist's colony north of Chicago, feature well-known figures—such as the innovative composer Lou Harrison and Harrison's life partner Bill Colvig, an instrument builder who collaborated with Harrison on gamelans and other percussion instruments. But they also include more personal choices: Larry’s undergraduate art instructors, St. Jack and St. Keith, for instance. “Jack was particularly influential in my pursuing art,” Larry recalls.  St. Elvira St. Elvira St. Elvira’s son Peter was Larry’s roommate and best friend during their days at the University of Kansas in the late 1970s to early 1980s. Elvira lived in New Jersey but had visited Peter and Larry in Kansas. “After I moved to New York City, she included me in holiday family gatherings when I wasn't able to get back to my own family in Nebraska. She adopted me as another son.”  St. Bill St. Bill In 2016, Larry and his partner Alan Zimmerman, a percussionist, traveled to San Francisco for a concert of Harrison's music to celebrate what would have been his 100th birthday. Two of Larry's art works (St. Lou and St. Bill) were exhibited at the concert, which was sponsored by the non-profit organization Other Minds.

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed