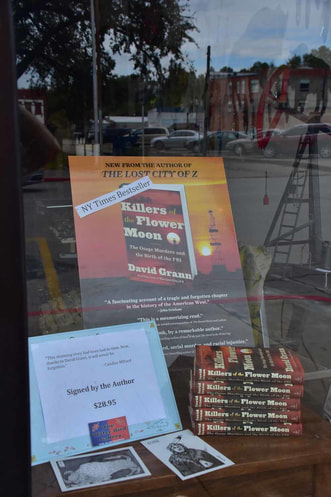

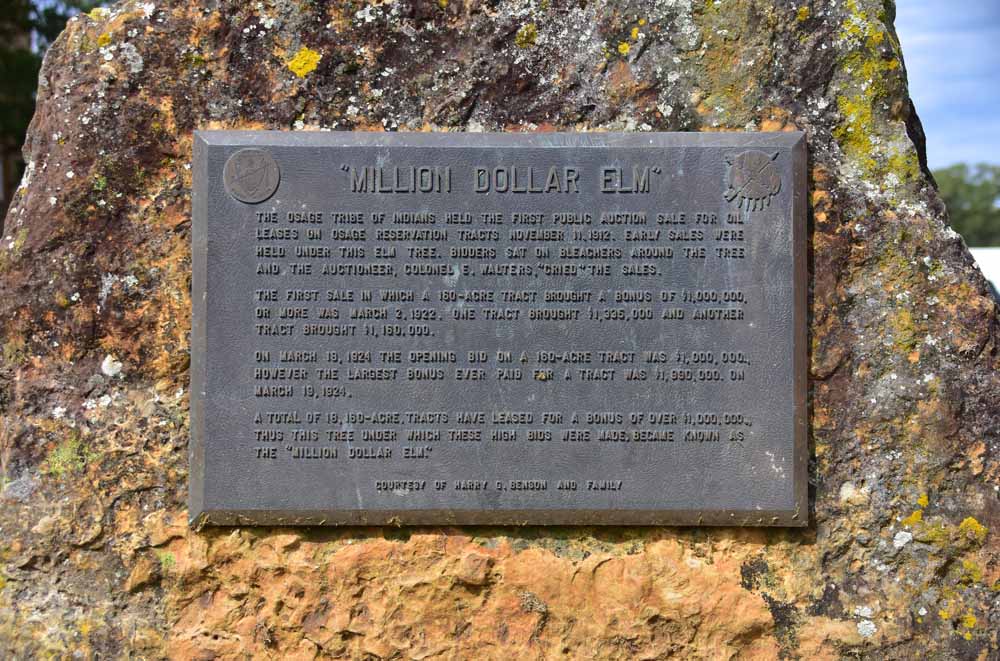

I scout the winners and finalists lists for to-read suggestions I scout the winners and finalists lists for to-read suggestions The 2017 National Book Awards were announced last week, and while I'm always interested in checking out the winners and finalists for additions to my To-Read list, I paid more attention than usual this year. That's because I was rooting for one particular book on the nonfiction finalist list: David Grann's Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI.  This book was the topic of many conversations in Oklahoma This book was the topic of many conversations in Oklahoma Although Grann's book didn't win in its category, its selection as one of five finalists speaks to the story's significance and the skill with which Grann researched and wrote it. That's reason enough to take note, but there was also this: Killers of the Flower Moon is the book everyone was talking about on our recent visit to Oklahoma. Cousins, classmates, complete strangers—all had read or were reading or were about to read the book and wanted to talk about it. Having just read it ourselves, and still feeling stunned by the story, Ray and I wanted to talk about it, too. In fact, we wanted to do more than talk, so while in Oklahoma, we made a pilgrimage of sorts to Pawhuska, the town where many of the events described in the book took place. More about that in a moment. To bring you up to speed if you haven't read the book, it's the true story of a series of murders of wealthy members of the Osage tribe in the 1920s. Forced onto seemingly worthless land in northern Oklahoma, the Osage had the foresight to secure collective mineral rights to the property, which turned out to be rife with high-quality oil deposits. By leasing the drilling rights to oil companies, the Osage made a fortune—more than $30 million in 1923 alone. (That's the equivalent of more than $400 million today.) At the time, the Osage were, per capita, the richest people in the world. They built mansions, owned fancy cars, sent their children to prestigious schools—and attracted the attention of schemers intent on separating them from their money by any means necessary, including mercenary marriage and murder. Whole families turned up dead from mysterious illnesses, secretive shootings and suspicious fires, as did investigators sent to look into the killings. With more than two dozen people murdered between 1920 and 1924, the killing spree became known as the Osage Reign of Terror. Eventually, agents from the newly reorganized Federal Bureau of Investigation solved the murders. Grann details that investigation and its devastating revelations, then—with the help of Osage Nation members he met while researching the book—goes on to unearth a deeper conspiracy. As Dave Eggers wrote in his New York Times review of the book, "Among the towering thefts and crimes visited upon the native peoples of the continent, what was done to the Osage must rank among the most depraved and ignoble." Growing up in Oklahoma, I heard stories—both official and personal—about injustices and atrocities committed against indigenous people. In Oklahoma History classes, we learned about the Trail of Tears (as well as the accomplishments of such leaders as Sequoyah and Quanah Parker). Yet I never heard or read a thing about the Osage murders, though Pawhuska is only 80 miles from my hometown.  Osage Nation Museum, Pawhuska Osage Nation Museum, Pawhuska Apparently, neither did most Oklahomans—including some you might think would have been well aware. At the Osage Nation Museum in Pawhuska, I overheard a conversation between another visitor and guest services representative Pauline Allred, an 87-year-old Osage/Ponca woman. "I guess you grew up hearing about the murders," the visitor said. "No," Ms. Allred replied. "We knew something had happened, but no one would say what had happened."  Books in gallery window Books in gallery window Today, the horrific story is no longer kept quiet; copies of Grann's book are prominently displayed in the window of The Water Bird Gallery in downtown Pawhuska. A monument on a nearby hilltop marks the spot where the Million Dollar Elm once stood. In the shade of that tree, auctions for oil and gas leases were held in the 1920s, with such notable oilmen as J. Paul Getty, Harry Sinclair and Frank Phillips bidding the big bucks that brought prosperity—and eventually tragedy—to the Osage Nation. Steps away from the Million Dollar Elm monument, exhibits in the Osage Nation Museum document that awful chapter, but place it in the context of a long history and rich culture. When we visited, the museum was preparing to open an exhibit by renowned Osage artist and activist Gina Gray, whose distinctive style blends traditional images with contemporary style. The nearby Osage Nation Cultural Center offers classes in traditional skills such as fingerweaving, moccasin-making, beadwork and ribbonwork, and the Nation's language department is actively engaged in revitalizing the Osage language through classroom and online courses. Encouraging signs of the Nation's resilience. Yet we also saw signs that controversy continues today, once again involving energy production. Approaching Pawhuska from the west, we drove through a vast wind farm. In town, we saw placards reading "NO TURBINES." We learned that the Osage Nation has been fighting wind development in the area for years, asserting that the enormous turbines—located on privately-owned ranches to which the Osage still retain mineral rights—are a "scenic blight" on the prairie landscape, and that the wind developments could disturb graves and archaeological sites. "They're eating up the landscape," said one Osage man quoted in a 2015 Tulsa World article. "They're devouring our history and culture." Several years ago, the federal government, acting on behalf of the Osage Nation, sued the wind farm developers, arguing that the construction process interfered with the Nation's mineral rights. Turbine construction involves digging a large pit for the foundation, crushing the underlying rock and using the crushed rocks as structural support. Though not a typical mining operation, the removal and altering of rocks does constitute mining, government lawyers maintained, and should not be done without obtaining mineral permits from the Osage Nation. The initial court ruling came down in favor of the wind developers. But the Osage Mineral Council appealed, and while we were in Oklahoma, the original decision was reversed. For the wind farm already in operation, the developers must negotiate a new lease with the Osage Nation, and any future developments must have the Nation's consent. How the situation will play out remains to be seen, but whatever the outcome, it will be one more chapter in the compelling story of the Osage of Oklahoma.

12 Comments

Laurel

11/22/2017 07:23:27 am

I've been wondering how Grann's book was received in Oklahoma and among the Osage - thanks so much for telling even more of the story and for your (as always) excellent photo-documentation.

Reply

Nan

11/26/2017 01:36:07 pm

Is it being talked about in your Seattle circles, too?

Reply

Laurel

11/27/2017 10:01:30 am

Not as widely as it should be!

Rachel

11/22/2017 08:24:22 am

what a compelling story! Thanks for this post Nancy-- adding the book to my-read list!

Reply

Nan

11/26/2017 01:36:40 pm

Definitely worth the read, Rachel.

Reply

11/22/2017 11:56:15 am

I agree the wind farms are eyesores on the landscape. We see them in IL. Looks like we are traveling through a science fiction movie scene, but no, the eerie giants are real. I have never heard this story of the Osage atrocities. So glad the truth is coming out. Your pictures are beautiful accompaniments to your story. Thanks for sharing.

Reply

Nan

11/26/2017 01:42:41 pm

Interestingly, the Cherokee Nation has embraced wind development in neighboring Kay County. However, they are keeping some historic sites turbine-free and limiting wind development to more sparsely-populated areas.

Reply

Susan Stec

11/22/2017 07:49:28 pm

Well, you have peaked my interest. I’ll put this book on my must read list.

Reply

Nan

11/26/2017 01:44:48 pm

Good! Let me know what you think.

Reply

Emily M Everett

11/23/2017 06:59:31 am

I just put it on my reading list, too. Thanks for the reminder!

Reply

Sue S

11/26/2017 04:15:15 am

Incredible story, thanks for sharing.

Reply

Nan

11/30/2017 08:42:07 am

Thanks for reading, Sue.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed