|

This is the last of ten installments in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. I posted the first nine here a year ago. Then I got sidetracked (life, right?) and never got back to post the final chapter. Now, a year later, I'm finally sharing it with you. A little background: Thirty-six years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. In the last installment posted here, I spent the final day of my visit to Samoa with friends Pili and Gretchen, attending their church service, enjoying good Samoan food, visiting a few familiar places with Pili and napping until time for my middle-of-the-night flight to Honolulu. Good to know:

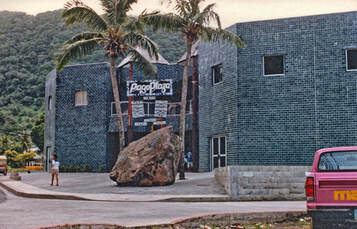

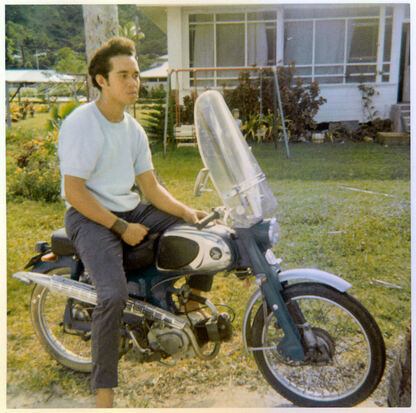

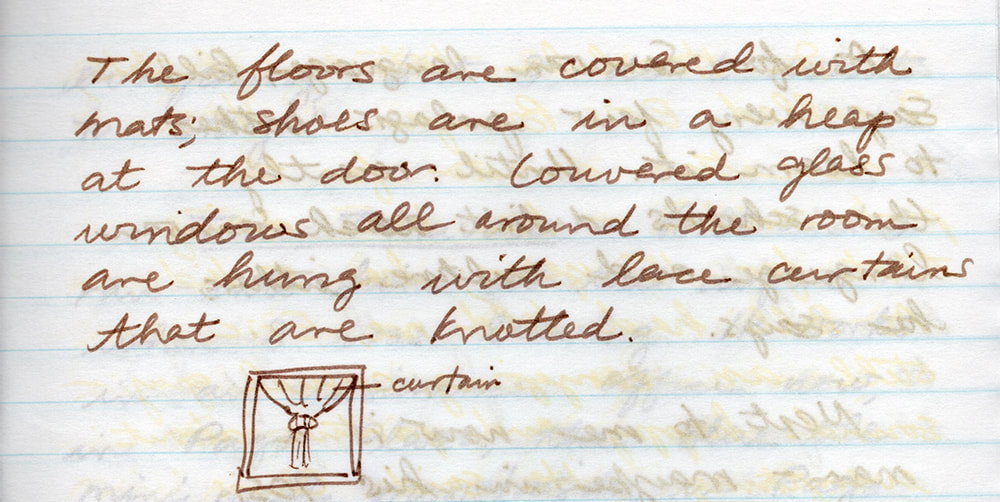

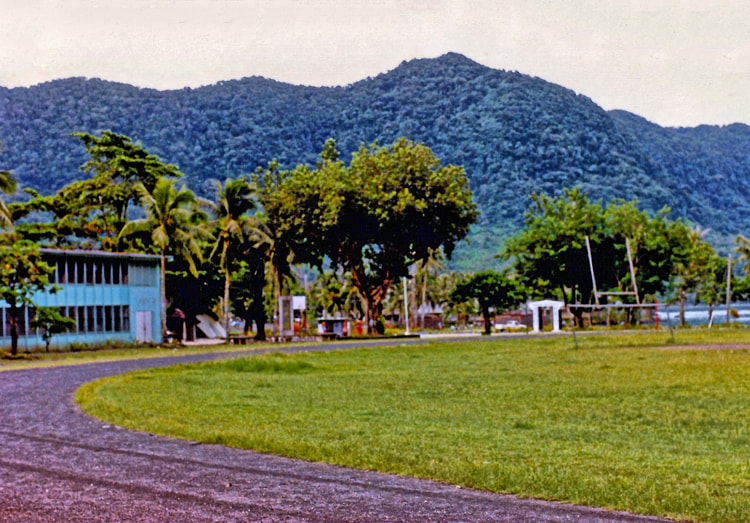

April 28, 1986Now I'm on a Hawaiian Air jet on my way to Honolulu. I'm just trying to remember vignettes from the past weeks -- trying to get as much as I can recorded before I forget things.  Traditional Samoan tattoos Traditional Samoan tattoos Samoan tattoos: Pili's daughters are showing me magazine pictures of a Samoan man being tattooed from waist to knee. Pili talks about the blood poisoning the men sometimes get. He says it's a great dishonor to start the process and not finish it. Men who only have partial tattoos go to great lengths to hide them, he said. Tui Letuli was telling me his father wants him to stay in Samoa and become a chief. Tui says, "I got my tattoos and everything, but I don't want to stay."  Pago Plaza, where my old friend Tau worked Pago Plaza, where my old friend Tau worked Tau Tanuvasa: Pili and I ran into him at the airport when I was leaving. He works in an insurance office now, in Pago Plaza, the blue tile mini-mall monstrosity in Pago Pago. I went to his office Friday, but he had gone home. He looks just the same as the kid who used to tool around in his "X-15" flatbed truck. Language: People seem to speak much better English in Samoa now. A lot of the people my age have spent time in the States or in the military, and they have excellent vocabularies. The young kids seem to speak pretty well, too. I don't know how it is for people who haven't been off the island, though. As for Samoan language, Pili says very few palagis bother to learn it. Until recently the schools didn't teach Samoan language and culture either, he says. * * * Next to me now is a man -- maybe in his 70s, wearing a gray business lavalava and jacket, with a mat wrapped around his waist, sandals on his feet. * * * Jeanette's father's house: A typical Samoan house for these times. It's up on a hillside in Utulei, in a cluster of other houses. You drive up a steep driveway, park at another house (Patrick Nomura's family) and walk the rest of the way up to his house. The bottom floor is one big room with a kitchen off to one side. The floors are covered with mats; shoes are in a heap at the door. Louvered glass windows all around the room are hung with lace curtains that are knotted. Hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the room are two shell chandeliers. Between them are a few coconut shell decorations. On the walls are some pictures of family members; one large portrait of a woman is hung with a candy lei. * * * Jeanette, Fatima, and I are at lunch one day. Jeanette starts to tell a funny story in English, then looks at me and says, "I have to tell this in Samoan." * * *  Eric in 1966 Eric in 1966 In Honolulu, between flights, I called Eric Bunyan. He's a recreation director for the park service -- has been doing that for 15 years; has 5 kids. As Pili had told me, Eric is still an easygoing, casual guy -- sounds happy and positive about everything. He said Chris Layne had just been down for a visit -- he lives in Seattle now, as does Marc Wiederholt. I told Eric about Pili's and my plan for the reunion, and he said he's thought about that, too. He says he'll start cleaning his yard right away. He said he and Chris Layne had been talking about me when Chris was there -- that there were rumors I had died because people stopped hearing from me after a few years. It surprised me on this whole trip when people told me my name had come up in conversations. And that those years and that group of people were as special to everyone else as they were to me. More vignettes Strangest scene was a Samoan man wearing a lavalava in his yard in some little village, cutting grass with a weed eater. I don't remember seeing any machetes. * * * Rainmaker Hotel had a strange feeling to it -- not quite decrepit, just indifferent. The air of grandeur was still there -- the high ceilings, shell chandliers. At first glance it's impressive. Then you start to notice things: dirty windows, water-stained carpets, worn-out, unmatched furniture, mismatched china, dirty tablecloths. My first day there it was very hot, so I got some ice and went to get some pop from the pop machine. First of all, the machine didn't say how much money to put in. So I put in 3 quarters, hit the button and waited. I tried another button and another. Nothing happened. Then I tried the coin return, but it was rusted into a rigid position and wouldn't budge. So I went back to my room to wash some clothes. I washed them and hung them on the towel rack. When I got them all up, the towel rack started falling apart. I'd get one bar up and another one would fall down, flinging my underwear across the floor. At night I would come out of my air-conditioned hotel room and walk through the open-air corridor to the lobby. I would always have to stop at the landing and look out at the bay in the moonlight. It was just about when I got to that spot that the tropical night air would hit me -- air that feels like it has mass, it's so dense with moisture and fragrance. I would hear the water slapping against the rocks and think about hundreds of other nights when I sat by the bay, feeling the same air, hearing the same sounds. There were nights sitting on Centipede Row, behind Val's house or behind the Wiederholts', sometimes just sitting and talking with girlfriends, sometimes waiting for a party to start, sometimes walking home from the movies, holding hands with a boy. Always there was a sense of excitement, expectation. When I stood on the hotel balcony, I felt sad sometimes, realizing that even if I found all my old friends, and we got together in the old places, we would never be able to recapture that special time when anything could happen. Now we're grown up -- we know what we've become, who we've married, what our children look like. There are still unexpected things ahead for all of us, of course, but they're all separate now. We're all going our own ways. Even the ones who are still on the island go their separate ways. Jeanette and Abe and Tima and Padilla see one another because they all play tennis. But Pili and Fipa only see others when their cars pass on the road. I guess that's the way it always is when you try to return to a place where you were young. The sights and sounds and smells may all be the same, but some of the mystery and magic will be gone forever. That's not to say I was disappointed. I would've been disappointed if I hadn't found anyone or if the ones I'd found had been indifferent. But some old friendships were strengthened and new friendships were made. I saw the place in new ways, too, as a place I want to know more about. Watching the Flag Day ceremonies made me think more about that, especially when I saw the singing and dancing group from Manu'a. I really wanted to understand the songs and know more about the traditions that have been evolving since these people found their ways through the Pacific to their tiny islands. THE END You're invited to enjoy a few more scenes from American Samoa in 1986

16 Comments

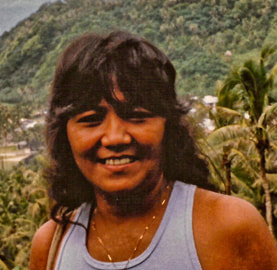

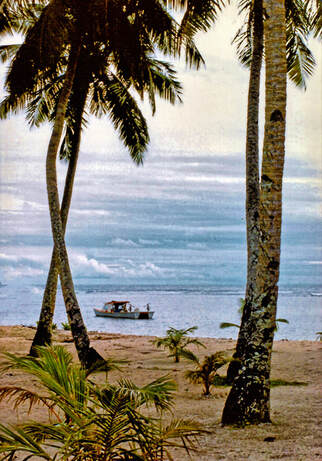

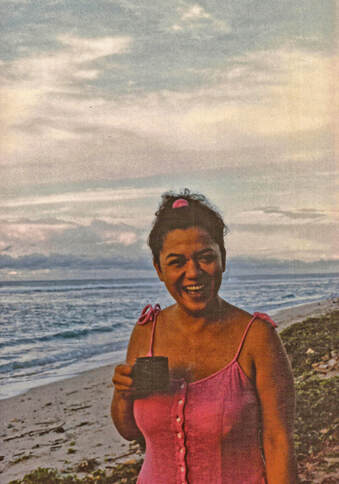

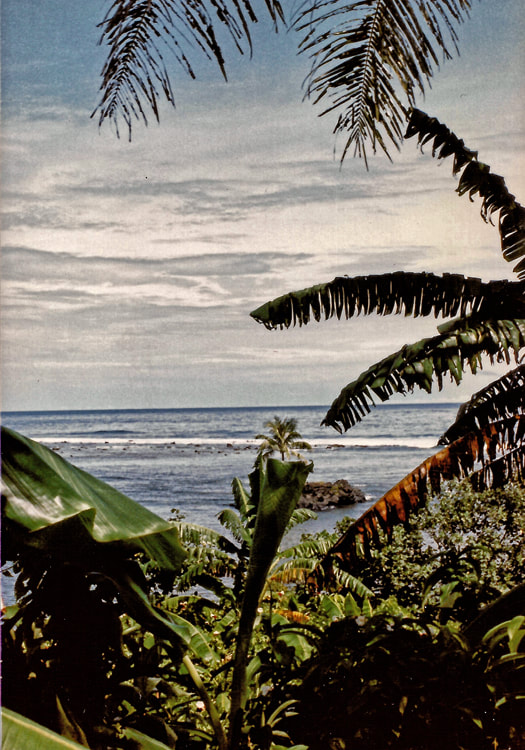

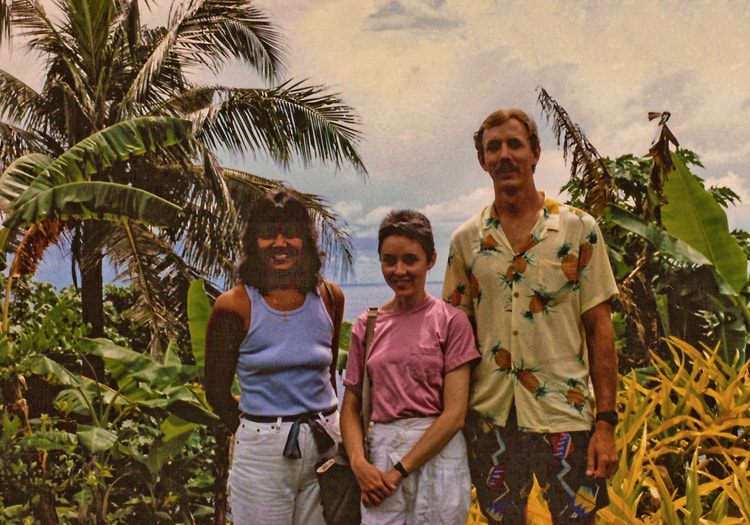

This is the ninth installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. In the last installment, I spent more time with old schoolmates and their families, and I accompanied my friend Pili to the Tikki Lounge, where his band Tropical Storm was playing. There, Pili introduced me to a young man who turned out to be Tui Letuli, the kid who stole my heart as a second-grader when I was a teacher's aide in his class. I spent that night at the home of Pili and his wife Gretchen. Today's installment picks up the next morning, my last day in Samoa before returning to Detroit. Good to know: Pili, Fipa (AKA Fibber), and Jeanette were all schoolmates in Mango Rash days Stillwater - my hometown in Oklahoma umu - traditional Samoan oven April 27, 1986 Pili and Gretchen's church meets under their house (open-air first floor) -- a dozen or so adults and kids sitting on wire patio chairs singing Baptist and Samoan hymns. I liked singing the Samoan hymns just to hear the words. Didn't know what most of them meant. It was kind of neat sitting there, watching the birds flitting around, seeing flowers everywhere, watching the rain. Everyone was cold -- it was probably 70 degrees. The one nice thing about leaving here will be not feeling clammy. I can't remember the last time my skin didn't feel that way.  Gretchen (in sleeveless dress) serves cake and ice cream after church Gretchen (in sleeveless dress) serves cake and ice cream after church After church there was cake and Samoan-made (Halleck's) coconut ice cream.  Bananas! Bananas! Then Pili's cousin (who went to school for six months at Stillwater High School) sent over food from his umu: taro, bananas and mackerel baked in coconut cream inside coconut shells. Wonderful. I'm really going to miss this Samoan food. Later we had chow mein, chicken, taro, cucumbers, rice. The day sort of slid by -- not how I really planned to spend my last day, but I was more into going with the flow than with trying to run around. Pili drove me into town and I took my last looks at the Leone to Fagatogo stretch. The rain had stopped and the colors were vivid again -- the hills all shades of green, from pale lima to deep emerald; the water in sparkling blues. Far from shore it's deep indigo, then it breaks white and foamy. The waves look turquoise witih the light showing through. And up over the reef, the water is calm, dappled blue, blue-grey in places. Sailboats and a motorboat were out on the bay. The waterfall was cascading down one of the mountains -- a steep, sheer veil across the bare rock face. Fipa had said he would stop by today, but I didn't get back to the hotel till after 2:00, and there was no message from him. Jeanette and Mai had called. Tonight at Pili's we watched TV, took naps. Now I'm waiting for Pili to take me to the airport. I just went out on the balcony. The sky is perfectly clear. The moon is bright, stars everywhere, low clouds around the horizon. Palm trees silhouetted against the glowing, grey clouds.  "Flower pot," one of my favorite places "Flower pot," one of my favorite places Funny thing how this place can drive you crazy one minute because of inconveniences but the next minute show you something spectacular you could never find anywhere else on earth, and make you feel like you never want to leave.  Nan in 1986, feeling at home again Nan in 1986, feeling at home again All week I kept going through contradictory feelings. At first I felt out of place and wondered how I ever felt at home in Samoa. But by the end of the week, everything felt natural. I'd really like to come down for a month (or a summer) sometime and spend the time writing about the place. I'd do it a lot differently next time. This time I didn't do much to prepare myself -- reading up, etc. I was so afraid of getting my hopes up and being disappointed that I just didn't want to think much about it before I got here. Now I really want to read more about Samoa and other Pacific islands. Pili's Pacific studies program is inspiring me, too. He showed me some books he's using and talked a lot about the things he learned. He told me the Pacific studies program was only started last year, though the college is more than fifteen years old. To be continued . . .

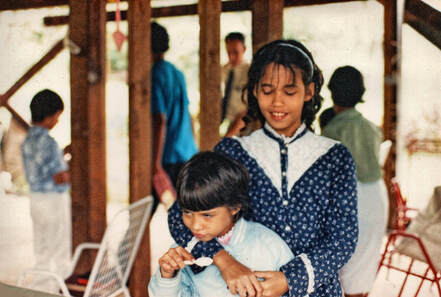

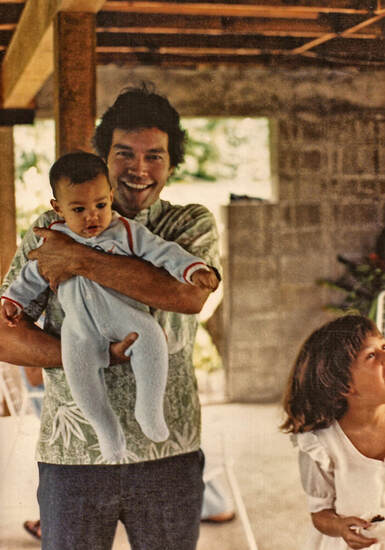

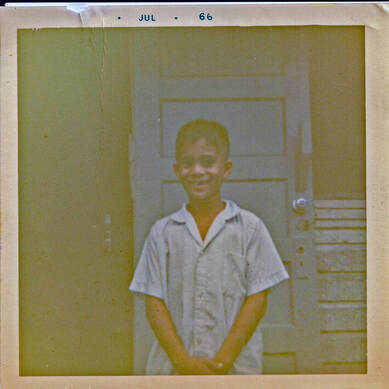

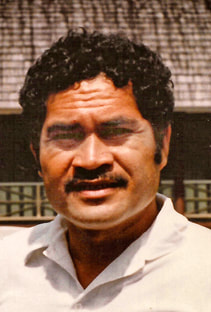

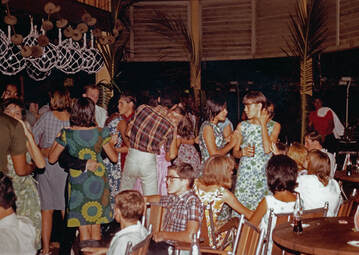

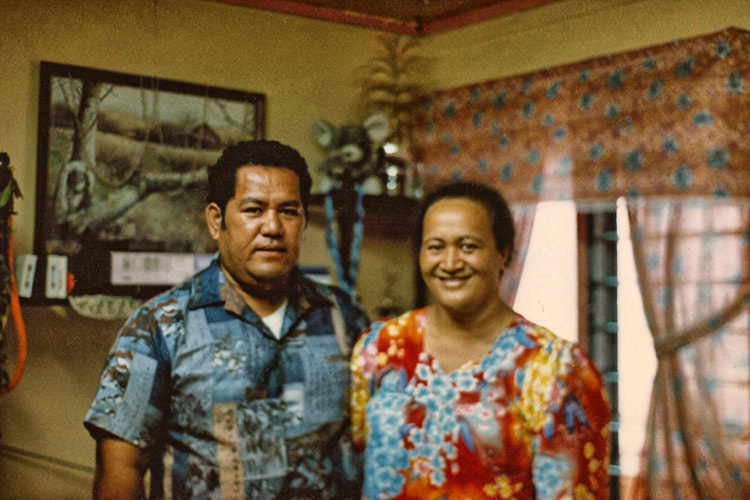

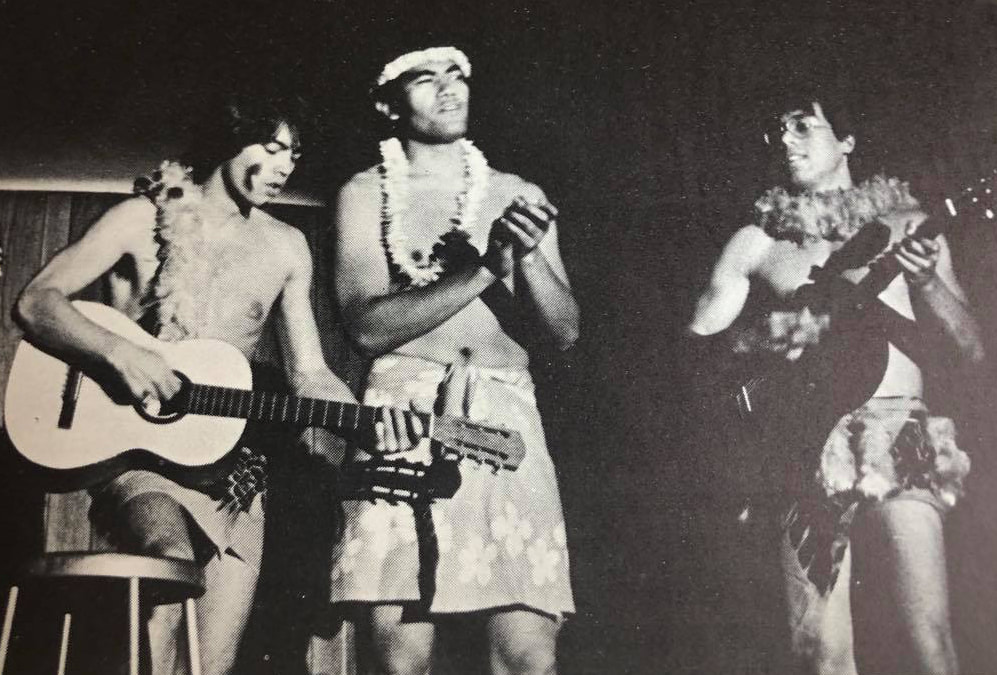

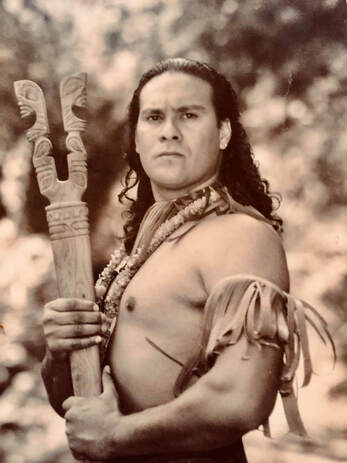

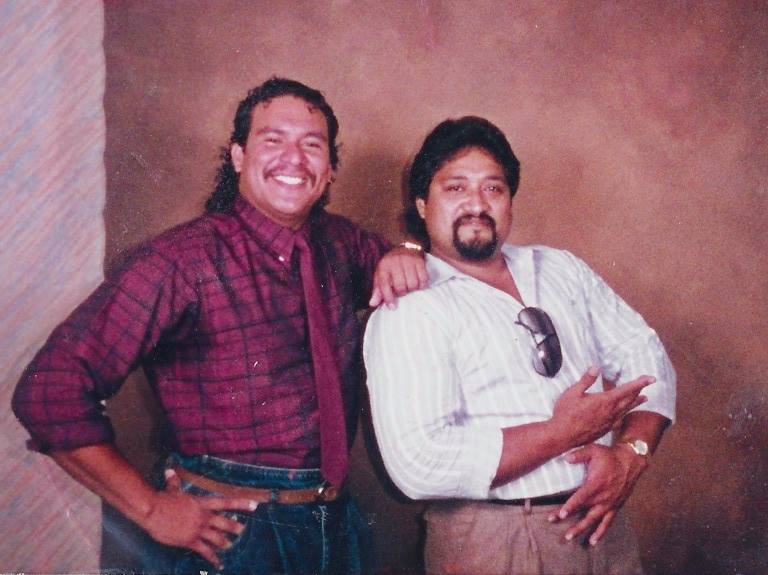

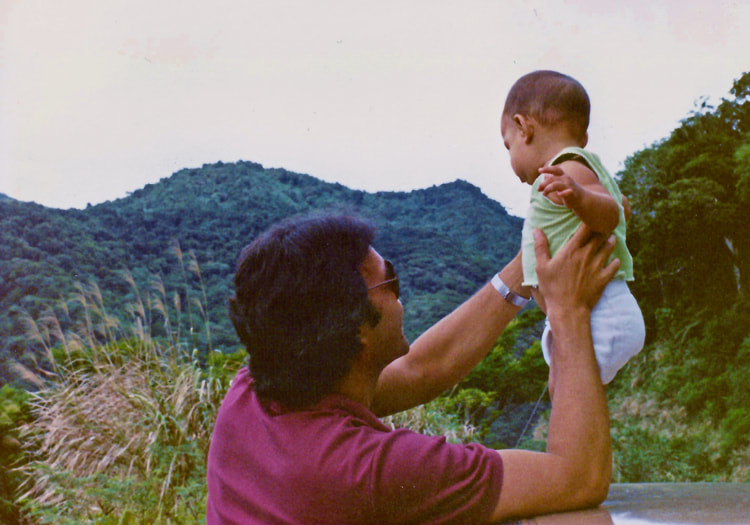

This is the eighth installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. In the last installment, I returned to the main island of Tutuila after a visit to the outer islands of the Manu'a group. Good to know: Tima - aka Fatima SPIA - South Pacific Island Airways Fipa - aka Fibber Mata Ala - Samoana High School's yearbook Afa Ripley - Former schoolmate Libya - My 1986 visit to American Samoa happened shortly after the US attack on Libya lavalava - wrap-around sarong aiga basket - baskets woven from coconut palm leaves and used for carrying just about everything, particularly food from the market or from special-occasion feasts April 26, 1986 Tima, Mai, and Jeanette came to the hotel for breakfast this morning. Then I went up with Jeanette to her dad's house, where they were preparing for her cousin's funeral. I found out all SPIA flights are cancelled through Monday. Tima had to make me new reservations through Hawaii. Pili came to get me and brought me out to his and Gretchen's house for dinner. We sat around the house; Fipa showed up -- had just gotten off work, wearing grease-splotched pants and scrub shirt, same kind of boots he used to wear, like motorcycle boots.  Danika and Melissa Danika and Melissa Pili's kids are great -- gregarious, polite. Danika is about 8 -- kept showing me family pictures; going through Pili's Mata Ala; showing me his college yearbook (the only picture of Pili was of him performing with a Polynesian group that included Afa Ripley, with black paint streaks on his face and long hair). Melissa is about 10 (?), beautiful, with long, wavy brown hair. Interested in science, very bright, aware of the world. We got out the atlas. She wanted to see everywhere I've lived, showed me Libya. She kept bringing out books and National Geographics, pictures of sharks and other fish, talking about astronomy and oceanography. Danika too -- talking about planets. Jon is a lanky teehager -- talkng back to the television, teasing his sisters.But he's friendly and doesn't seem self-conscious.  Pili and Caleb Pili and Caleb Caleb, the baby, is sweet-natured, attentive,with big brown eyes in a little brown face. Tonight I went with Pili to the Tikki lounge to hear him play with Tropical Storm, the group he's with now. He's still got it with the drums. I missed the old music -- this group is into Dire Straits, Huey Lewis, Stevie Wonder. But they did play two Samoan songs. It was exciting to hear that and to see people dancing. I was hoping there'd be someone to dance with, but most of the people there were couples or in groups -- a wedding party, the girls' netball team from Apia. Pili and I danced to the disco music at the break. It was really like old times.  Tui in 1966 Tui in 1966 Just before the last set, Pili took me outside to meet someone. It was Tui Letuli, the kid I used to tutor in reading when he was in second grade. He's now 28, plays lead guitar. He's traveled all around the States, performed in a lot of places, getting ready to go back to L.A.to hang out. I spent the night at Pili and Gretchen's. Watched pigs running through their yard. Pili complains about them rooting up his papaya trees. Guys walking down the dirt road wearing lavalavas, carrying aiga baskets. To be continued . . .

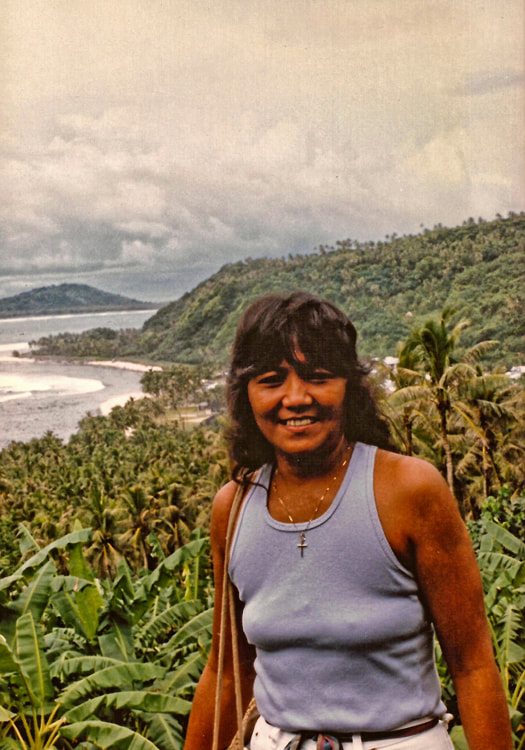

This is the seventh installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. In the last installment, I traveled with former schoolmates Abe and Robin and another woman to the outer islands of the Manu'a group: Ta'u, Ofu, and Olosega. At the time, Abe was overseeing public works and power projects throughout American Samoa. Good things to know: fale - Samoan for house Soli & Mark's - a popular local restaurant fa'asamoa - literally, "the Samoan way." The traditional way of life in the Samoan culture palagi - white-skinned person, foreigner taupou - ceremonial hostess, an honorary position puletasi - traditional Samoan dress April 25, 1986 We're up at 6 am, watching a shell-colored sunrise, then having coffee and walking by the beach. We figure Abe has been up for hours inspecting more public works projects. Just before the plane is due in, we check his room and find him asleep -- he'd been up till 2 am, talking business. Back in Pago, I box up my stuff to send home (hiking boots, heavy sweater), lug it to the post office. Have more frustrating phone experiences.  Abe Abe Abe comes by for lunch. In three hours, he's had two meetings with the governor; signed checks; had an explosive argument with the budget director, who is refusing to approve construction of a new administration building; plus several other things I don't remember. We go to lunch at Matai's Pizza Fale in Nu'uuli's shopping center. We talk about Abe's trip to Washington (leaving tomorrow morning). He lights up when I tell him I'll try to get him a picture of Lee Iacocca. He starts telling me about the house he's building near the airport, and he gets that kind of explosive glow again. "Oh!! Do you want to drive by it?" We do -- he's having it built by a contractor from Texas -- more expensive, but good work, he says. He's building it for his parents' retirement. This afternoon I wandered around, took pictures, bought more shirts, miscellaneous Samoan stuff.  Fatima Fatima Fatima took me down to Pago, where I looked for Tau at his insurance office, but didn't find him.  Jeanette Jeanette Then we met Jeanette at Soli & Mark's. She and a friend were having an interesting conversation about fa'asamoa, saying that no matter how long you spend off the island, "no matter how palagi you think you are," you always have to deal with Samoan customs. It's more a part of you than you realize. Jeanette is caught up in it now because of the funeral for her cousin (Ray Nomura's son), who drowned off Aunu'u. The other woman is into it because her father is taking over the high chief title on Ta'u. There, fa'asamoa is really fa'asamoa. In the kava ceremony, she won't be able to get near where her father is, for example; no picture-taking. And their lives will be different -- she can't sit in her father's chair, lie on his bed, or eat his food. Tonight, Jeanette, Mai, and I sat around in the bar at the Rainmaker, drinking. It was a good time. Then as we were going through the lobby, we saw that they were showing the Miss Flag Day competition on TV. We came in as they were having the kava ceremony competition -- the taupous doing the kava preparation, flinging the kava strands back over their shoulders. Then we saw the puletasi competition -- some of the women barefoot, shell decorations and jewelry. To be continued . . .

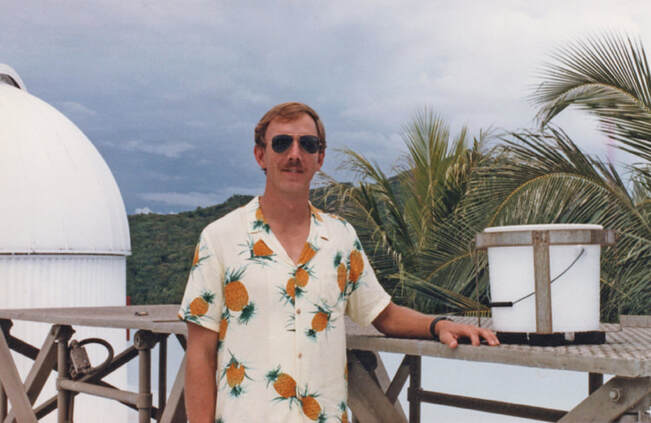

This is the sixth installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. In the previous installment, my Samoana high school friend Abe invited several of us classmates to come with him on a trip to the outer islands of the Manu'a group: Ta'u, Ofu, and Olosega. At the time, Abe was overseeing public works and power projects throughout American Samoa. Four of us made the trip: Abe, classmate Robin, another American woman named Karen, and I. April 24, 1986 This morning the weather looks awful. Last night it was storming -- high seas, boulders across the road, fallen trees. Today the skies are gray, foreboding. But I don't want to disappoint Abe, so I go to Manu'a. We fly in a tiny plane -- twelve passengers. From Pago airport, it's 30 minutes to the dirt landing strip at Ta'u. The strip there is a swath cut through banana trees; taro grows within yards. There's no terminal, simply "Welcome to Ta'u," from the pilot. Then we buzz back into the sky, and in five minutes we're in Ofu. I was dreading the landing there, but to my surprise there's a new concrete runway and the landing is perfect. The runway is one of Abe's public works projects. We're met by John, a Samoan wearing an L.A. Raiders cap. He has lived in San Francisco, speaks with an American accent. He's been in charge of a project to build a road to a peak on the island for a TV tower. Abe sees a street light on that should be off -- the photo cell isn't working. On the way back to the motel, he's counting how many are defective.  Abe Abe John takes us for a ride around the island, and we see Abe in action, pointing out to John areas of the road that need to be improved. He asks John how far from the top the road is now. John says, "About 200 yards." Abe says, "That's what you told me a month ago."  Ofu scenery Ofu scenery The rest of us are enjoying the sights, sitting in the back of the pickup. There is white sand everywhere--even people's front yards are covered with it. The houses are clean, painted sweet pastel colors. The water is turquoise and sparkling, with live coral. Abe says the drinking water is very pure. (It comes from underground springs). Only about 1,000 people live on the two islands, Ofu and Olosega, that are connected by a bridge Robin says cost $1,000,000. The people of Manu'a are wealthy, I hear it said by several people. They have very little to spend money on, so they save everything. Their taro is considered the best. It's whiter, not as sticky, almost a fluffy texture like heavy bread. Abe checks the power plant, and Robin, Karen and I walk around the dock area and along the road, down by the little cafe. Karen tells us bizarre stories about her life. We get back to the plant; Abe is taking a nap on a mat on a bed. John drives us back to the motel. On the way we meet another of Abe's employees, who is bringing us boxes of food: pork, chicken, taro, palusami, and what Robin calls chow mein--cellophane noodles mixed with corned beef. After dinner, Robin and Karen watch TV and talk about Karen's problems, and Abe and I sit on the beach talking for a long time. He says he envies Bill for his stable family life. (Bill envies Abe for his seriousness and studious nature.)  Robin Robin When it starts raining, we go inside and make coffee and sit around and talk some more. Karen falls asleep, and Abe, Robin, and I talk about our compulsiveness at work -- how we all avoid personal relationships if they interfere with our work. It strkes me as very ironic that we're all on this serene, relaxing island, miles from our responsibilities, but we end up talking about work. Robin and Abe: the Samoan yuppies.  Frangipani Frangipani About 11:00, we go to our rooms. I sit outside watching the clouds in the dark sky, listening to the ocean, smelling the frangipani blossoms. We would have slept soundly, but we were dumb enough to leave the door open, and mosquitoes were all over us. I had to keep the sheet completely over me -- face and all -- to keep from getting bitten about once a second. To be continued . . .

This is the fifth installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. April 21 - Connecting with friends The days are so full I can't begin to record everything. Today I began to feel comfortable here -- like I used to.

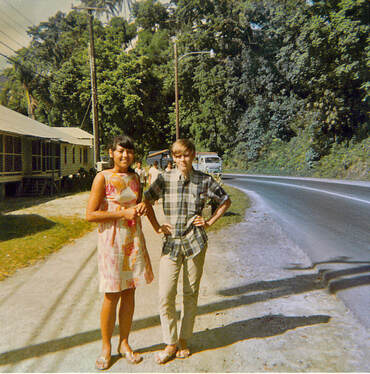

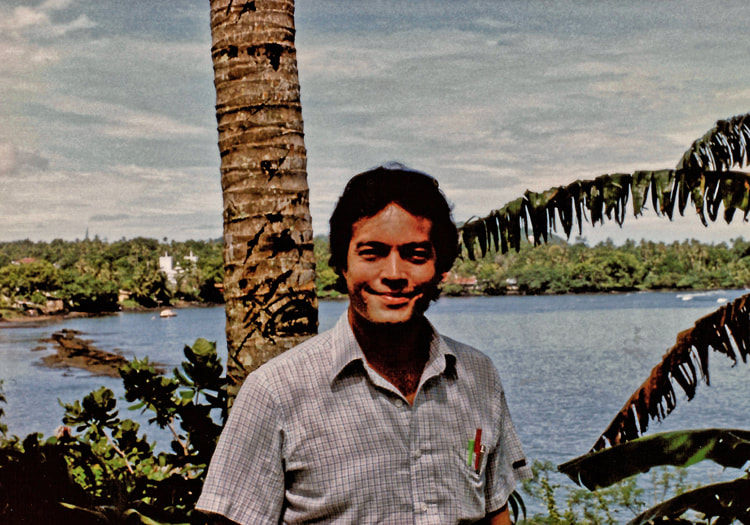

Pili and I drove around the west end of the island and over to the north shore. Fantastic scenery -- blue water, dense jungle, white beaches -- Samoa at its best. Met his friends Tui and Donna (Tui is Sualua's younger brother) and the Baptist missionary from Eureka, California. Pili dropped me off at Jeannette's, where I had dinner with her and Gordon and their family (3 kids). Padilla and his wife stopped by. Jeannette and I went back to the hotel; had coffee and a good talk. [Several paragraphs of personal details from that conversation omitted for privacy.] After coffee, we went up to the bar, where Fatima and Pat Galea'i and some other people were drinking -- sat with them for a couple of hours. Had a good time, but they were getting rowdy. I'm glad I found Jeannette, though. She's very intelligent, thoughful, concerned with world affairs. Tomorrow we're going to go for a drive on the east end of the island; also to find some more people -- Fipa [Fibber], Robin, and others. April 23 - Stormy weather One of those highs-and-lows days. Right now I'm in my room with a fierce tropical storm raging outside. I can hear the wind whistling outside -- palm trees blowing all around. Power just went out. April 24 - Continued connections Had to stop writing last night because the power went out again. Really bad storm last night. [What follows are further details from April 23.]  Fipa (Fibber) in 1966. I regret not taking photos of him in 1986. Fipa (Fibber) in 1966. I regret not taking photos of him in 1986. Jeannette and I met for lunch at the airport. I bought some stuff from her friend's shop there. Then we went to see Fipa, who is a mechanic for the Department of Transportation. Fipa looks much the same. No front teeth, less hair, but still the same Fipa. Tonight we all met for dinner at Soli & Mark's: Pili, Robin Annesley, Jeannette, Padilla and Teuilla (his wife), Fipa, Fatima, Abe Malae and I. It was a great time. I sat between Abe and Pili most of the time. Abe told us how he got into Motown music. Now he has just about everything ever recorded, plus lots of other stuff from that era. He asked Pili and me what other records he should order from the Columbia record club. He also told me that Lee Iacocca is his personal hero.  My 17th birthday party in 1966, approved by Abe My 17th birthday party in 1966, approved by Abe It's funny the things people remember. Abe remembered that I was from Stillwater, Oklahoma. He also remembered the party invitations for my birthday, and that I asked him if he thought it was OK for me to have a party when I was running for student council vice president. I used to confide in Abe a lot. Fipa remembered me telling him I was going back to the States for cancer treatment. He says we had this conversation up on Mt. Alava. I don't remember it. Pili is embarrassed about being a goof-off in high school. But we all thought he was very personable. We envied him for that. Abe decides we should all go to Manu'a with him tomorrow (Thursday). He has to go over to inspect public works projects. He gets so excited -- he really lights up talking about it. Pili, Robin, Jeannette and I say tentatively that we'll go. To be continued . . .

This is the fourth installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. Good to know before we begin:

April 20, 1986 - Day two Rainmaker Hotel lobby Rainmaker Hotel lobby A really good day. I had breakfast in the Rainmaker's dining room -- a big improvement over the snack bar. I had lots of papaya and pineapple, lamb ribs, fish, eggs, taro with coconut cream. Then I went for a walk, came back and called Pili. He and Gretchen came by with their youngest son Caleb, and we all went for a ride over to the other side of the island to the village where their friends Vernon and Limu live.  Mountain pass Mountain pass Spectacular scenery on the mountain pass. I may drive back up there if I can get a car. Their village is in a little cove -- picture-postcard Samoa. Mostly new style houses, but very pretty -- white stucco, bright colors. All around the village, young men were sitting around grating coconuts. Vernon and Limu's house is modern. We sat around drinking Vailima (beer made in Western Samoa), half-watching movies on their VCR and talking about their jobs and Samoa today. Vernon teaches Phys Ed at the community college where Pili also teaches. Both said they get several thousand dollars a year for "supplies," but are not allowed to spend it on equipment, which is what they really need. Vernon said the locker-room washing machine has been broken since November. Can't get it fixed or replaced. Pili said he's trying to do an oral history project but doesn't have enough tape recorders and can't get them.The restriction on equipment apparently came because people were ordering video and other equipment and taking it home.

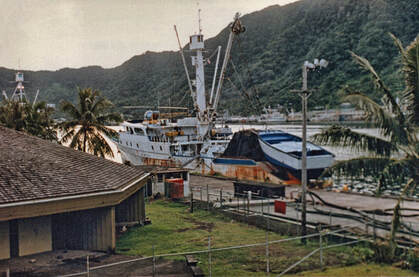

The old fale at the airport was dismantled to be used in a cultural center at the college. But it was done by Public Works Department workers with hammers and saws instead of by craftsmen. It had been put together in the traditional way, with no nails. Pili says it's in storage now and will probably rot before anyone puts it up.  Purse seiner Purse seiner Another local concern is the purse seiners working out of the harbor. They've only been working the area a few years but have already overfished for tuna. The wahoo they just throw away or give to visiting dignitaries. Local people are outraged at the waste. To be continued . . .

This is the third installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. A note of clarification:

April 19, 1986: First dayAt breakfast I meet two other guests -- airline company consultants from California and B.C. They ask why I'm here. I say I used to live here. One says, "Wasn't that enough?"  The new addition to Apiolefaga Inn was under construction, but at least one guest stayed in it The new addition to Apiolefaga Inn was under construction, but at least one guest stayed in it The one from B.C. says he was last here 10 years ago, and nothing has changed. The other one says he slept last night in the new addition -- an unfinished structure behind the main building. He stayed on the second floor, where there are balconies but no railings. "I'm glad I didn't come in drunk," he says. Breakfast ($3) was Kellogg's Apple Jacks -- as soggy as the cardboard they're packaged in. Then a tomato omelette and three enormous pancakes.  I watched chickens pecking around this shelter and thanked them for my breakfast omelette I watched chickens pecking around this shelter and thanked them for my breakfast omelette During breakfast I watch chickens walking around outside and feel myself settling into the pace. 11 pm  Remembering Daisy and happy times together Remembering Daisy and happy times together The rest of the day had a sad edge because of something that happened this morning. A woman named Debra from the tour agency picked me up at Apiolefaga to drive me to the Rainmaker. On the way, we were talking about where I used to live in Utulei, and she asked me if I remembered Jessop bakery. I said Thomas and Daisy Jessop were good friends when I lived here. She said she was their cousin. Then she told me Daisy died of cancer this year. She had 4 children -- the youngest only 2 or 3 years old. All day I haven't been able to stop thinking about Daisy -- wishing somehow I'd managed to find her, feeling so sad for her. Random observation: Debra, Daisy's cousin, looks like she just flew in from Bloomfield Hills. Dark, honey-colored hair, cut short and curly; long, red nails; lipstick, perfect makeup; stylish clothes; driving a new Honda. The only tip-off is the band of intricate tattoos around her wrist. Another weird thing was, I picked up a copy of the Samoa News and on the front page was a picture of a young woman dancing at the Flag Day celebration. It was Barb (Pegues) Scanlan's daughter. That was a shock. I figured Barb* had taken her with her if she left here, but apparently not. I'll have to see what I can find out.  Motu o fiafiaga - Islands of happiness Motu o fiafiaga - Islands of happiness A more upbeat thing was talking to Pili Legalley. He was very friendly -- invited me out to his wife's 30th birthday party, but I didn't go because I wanted to get cleaned up, wash some clothes, try to call home. But maybe I'll go out there (Leone) tomorrow.  The former hospital where my dad worked. It was replaced by a new hospital after we left, and this building was converted to government offices. The former hospital where my dad worked. It was replaced by a new hospital after we left, and this building was converted to government offices. I walked around town a lot this afternoon, going in the stores. Nia Marie, South Pacific, other familiar ones. They seem just the same -- selling the same fabric, cheap perfume, plastic jewelry. To be continued . . . * I changed Barb's name to Marnie in Mango Rash, to avoid confusion with "Graffiti Barb."

This is the second installment in a series of posts commemorating a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). In this series of posts, I'm sharing excerpts from my 1986 travel journal, along with photos from the trip. A few notes of clarification:

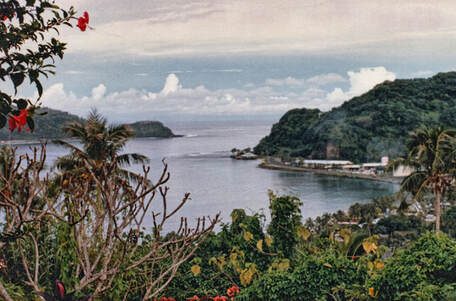

April 18, 1986 - First night View from Apiolefaga Inn View from Apiolefaga Inn At first I think I'll just go to my room, clean up and sleep. Then I decide to call this woman Ruby Tuia, who was supposed to pick me up at the airport. There follows an absurd conversation in which I try to tell the person who answers (Ruby is out) that I'm calling to tell her I did get in and am at the hotel. She says, "But a Miss Ross already came in -- aren't you that person?" Finally, we realize that I am calling another number in the hotel from the front desk, and the person I'm talking to is the woman who checked me in. We laugh -- it breaks the ice.  Samoan food brought back so many memories Samoan food brought back so many memories I decide to give dinner a try. First she brings out a bowl of tepid cream of tomato soup, and I figure I'm getting standard tourist fare. Then she brings a big covered plate and lifts to top to reveal a whole spread of Samoan food -- raw fish, palusami, pisupo, boiled bananas, rice balls. It's wonderful, especially the palusami. I pass on dessert, fearing Samoan pudding. (Dinner was $6.)  Plumaria, AKA frangipani Plumaria, AKA frangipani Now I'm in my room. Until a few minutes ago, I could hear music drifting in from somewhere -- the same kind of music I remember: electric guitars. And ever since I got off the plane, I've smelled that smell -- that heady mixture of ginger and plumaria, rain and coconut oil. I wish I could bottle it and bring it out for a sniff whenever I need to feel secure and peaceful. Tomorrow, if all goes as expected (and nothing has yet), I'll get to the Rainmaker, get myself organized, call home, go downtown, and start trying to renew old acquaintances. Now I'll try to go to sleep. The music has started again, and outside my window are Samoan voices. But first I have to describe my room: mint green cinder block walls; floor covered in a patchwork of different patterns of no-wax tile -- mostly in shades of green, gold and brown, with splashes of Delft blue and terra cotta. The curtains are a different shade of mint green with a palm leaf pattern. The bedspreads are brown and gold tapa designs. There's a refrigerator in the corner, but it was only plugged in when I checked in so I'm not terribly comforted by it. There's a huge closet -- without hangers. But the pièce de résistance is the table lamp on a long, low bench beside the bed. The shade alone is about the size of a 55-gallon drum, and the rest of the lamp is to scale.The base is iridescent white with simulated hand-painted flowers on it. I think the lamp is bigger than the bed.  Resting up to take in sights like this tomorrow Resting up to take in sights like this tomorrow Well, time to start relaxing. To be continued . . .

I'm temporarily reviving my blog to commemorate a very memorable journey. Thirty-five years ago this month, I paid a visit to American Samoa. At that time, it had been twenty years since I left there after spending one of the most unforgettable years of my life on the main island of Tutuila -- a year chronicled in my memoir Mango Rash: Coming of Age in the Land of Frangipani and Fanta (Behler Publications, 2019). I recently unearthed my travel journal from that 1986 trip. Over the coming weeks, I'll share excerpts from the journal, along with photos from the trip. A few things to explain before we set off for the islands:

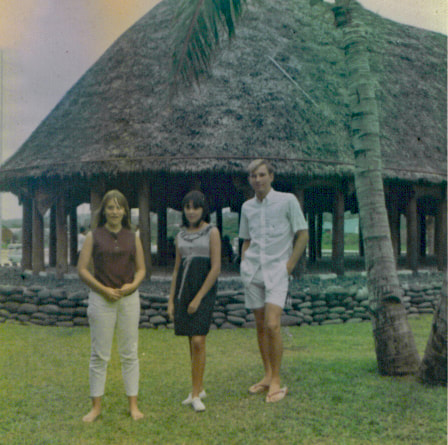

April 18, 1986 - ArrivalStarted out in Aukland, where I spent the night. A very strange night, too. I had thought I'd check in, send my last story, then have a beer in my room, watch TV and go to sleep. But the phone receivers were too big to fit in the cuffs, so I tried to work something else out, but no phones in the place would work. So I had to wait till I knew someone would be at work in Detroit--after midnight Aukland time. I kept dozing off and waking up because I couldn't find my alarm clock and didn't want to rummage through my luggage. When my editor got in, she had Lois [the department assistant] call me back to take dictation at about 3:30 a.m. my time. All night I was taking little naps, dreaming, waking up and talking on the phone, going back to sleep. After awhile I didn't know what was real.  Me in 1986, rising to the occasion Me in 1986, rising to the occasion I felt awful this morning--in no mood to start off on an adventure. But I tried to rise to the occasion.  The tropical scents helped ease my travel stress The tropical scents helped ease my travel stress At the Aukland airport,I got my first reminder of fa'a Samoa. I checked in early and got down to the gate about an hour before the 10:00 flight. At 9:30, when the flight was scheduled to start boarding, there was no one in the lounge--just a few other palagis and one Samoan woman with two babies. We boarded about 9:45--still only a few more people had drifted in. But once we were on the plane, at about 10:00, suddenly hordes of Polynesians swarmed on. The next reminder was on Samoan personalities. I had forgotten that while Samoans may be friendly and warm, they're not outgoing (toward palagis, at least). They don't initiate conversations, and they may not answer you if you do.  Western Samoa from the air Western Samoa from the air We arrived in Western Samoa, and the next reminder was the unbearable heat and humidity. It's like being locked in a bathroom where someone just took a very long, very hot shower. I remembered it, but there's no way the memory can approximate that suffocating feeling.  I could put up with the hassles, knowing scenes like this awaited I could put up with the hassles, knowing scenes like this awaited We got in the terminal. I struggled through customs with my bags (of course, no luggage carts--the terminal is just a big barn with open rafters and ceiling fans). Then the customs inspector said, "This fellow will take your bags for you," and I thought "great." But the fellow just carried my bags out the door and dumped them on the curb in the midst of a mob as unyielding as only a Samoan mob can be. In the heat and humidity, I tried to load up the luggage cart I had finally found, feeling kind of idiotic but realizing there was no other way to get the 30 feet to the baggage check for the next flight. Remembering my first day in Samoa in 1965, I had tried to prepare myself for that scene. But still, it came as a shock--the hordes, the heat, the feeling of isolation when no one talks to you and they all talk to one another in a language you don't understand well. I had bought film in Tonga so I could take pictures on the way to Pago. But I absent-mindedly checked the bag with my camera in it. As it turned out, it was getting dark when we approached American Samoa. And it was hard for me to recognize things from the air.  This photo from 20 years earlier -- 1966 -- shows the fale where Samoans used to wait for arriving passengers. It was no longer there in 1986. L to R: Barb Pegues (AKA "Marnie" in Mango Rash), me, a friend named Don Lee (who's not in Mango Rash) This photo from 20 years earlier -- 1966 -- shows the fale where Samoans used to wait for arriving passengers. It was no longer there in 1986. L to R: Barb Pegues (AKA "Marnie" in Mango Rash), me, a friend named Don Lee (who's not in Mango Rash) At the airport, I was disoriented because I didn't see the old fale. Finally I saw where it had been, but only the base is there. The airport seemed deserted, compared to what it used to be like--maybe it's still that way when big flights come in.  Apiolefaga Inn Apiolefaga Inn Someone was supposed to meet me, but when I was still standing there 45 minutes after the plane came in, I took a taxi to the Apiolefaga Inn.  Hibiscus Hibiscus You come in to a big room with a second-floor balcony all around it. There are tables all around, each with a vase of tropical flowers. Linoleum floors, sparkly plaster ceilings and a collection of chandeliers that looks like someone had a friend in the lighting department of Kmart. They all have prisms and more prisms--mostly dingy and covered with cobwebs.  View from Apiolefaga Inn View from Apiolefaga Inn I pay for my room--$36 for a $35.70 room. The woman says, "I owe you 30 cents--I'll give it to you later." She takes out a book to write me a receipt and stuffs my money into the book along with several hundred-dollar bills stuck in the pages. I look in the guest register--see names from Denver, London, lots from California. Wonder what brought these people here and what they thought about the place. TO BE CONTINUED . . . Note: I'll be taking a medical time-out next week, but I hope to pick up on these posts the following week. Check back on April 21.

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed