|

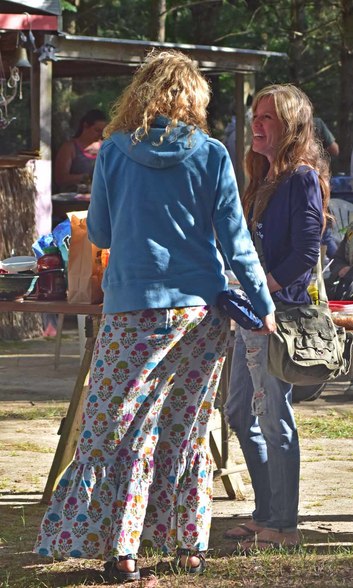

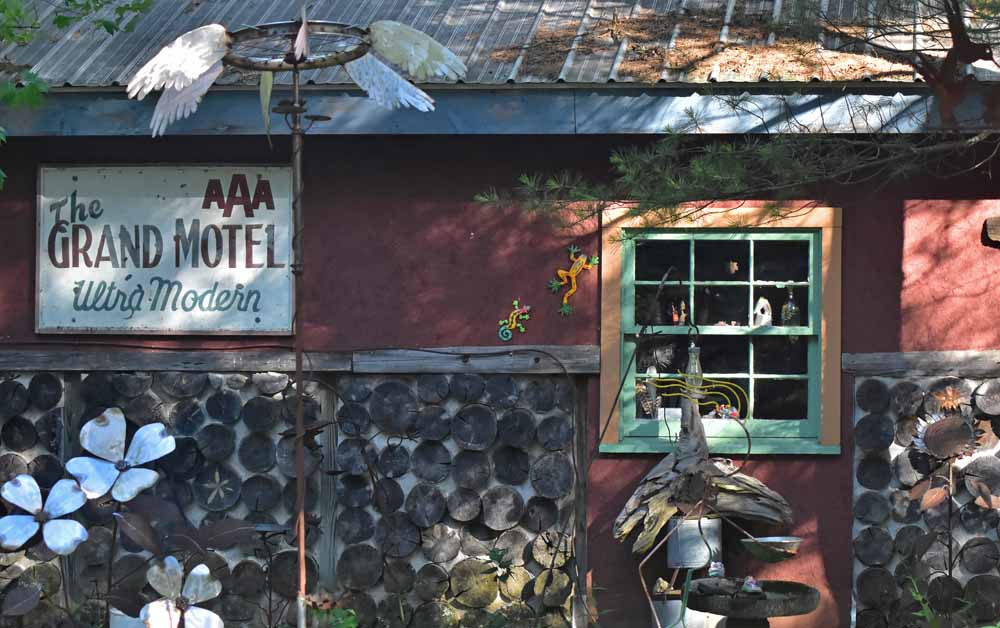

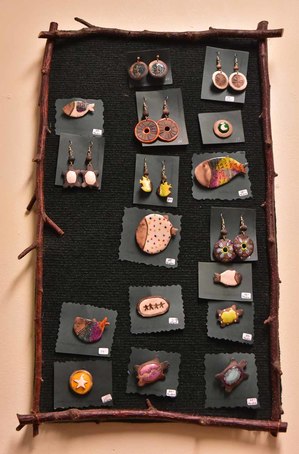

I've been to reunions. I've been to festivals. I've even, in my day, been to a fair number of hippie love-ins, be-ins and other gatherings of the tribes. But nothing quite compares to Creekfest, an annual event hosted by our friends Paul and Valerie.  Now in its 25th year, Creekfest is a reunion of "kin," who may or may not be related in a strict genetic sense, but who all share genes for enjoyment of good music, good food and good times.  Imaginative art work adorns even the camping areas Imaginative art work adorns even the camping areas Held on Paul and Valerie's wooded property on Coolbough Creek, the event goes on for a full weekend, with many of the 150-200 or so attendees camping on the premises.  This year's Creekfest schedule This year's Creekfest schedule Things get rolling Friday evening, when local chef Tracy Murrell offers Thai specialties. Music and merriment typically follow.  Creekfest's got talent! Creekfest's got talent! Saturday is activity-packed, with a kids' craft and painting party, tie-dye for anyone who wants to get colorful, and a rubber ducky race on the creek. This year, Ray and I arrived just in time for the tail-end of the pre-dinner talent show, an impressive display of musicality by youngsters and not-so-youngsters.  The setting is part of the appeal The setting is part of the appeal Part of the fun is just taking in the setting. The "cabin," its additions and outbuildings have been constructed over the years with the help of friends. And everywhere you look are Paul and Valerie's creative touches, from Paul's metal sculptures to Valerie's moss gardens, to various intriguing objets d'art placed here and there. You could wander around for days and still not see everything. After Saturday's talent show came a potluck to top all potlucks. I swear the spread was half a block long. Well, maybe not quite, but it just kept on going. All the dishes got rave reviews, especially one beet salad with goat cheese and walnuts. (Did you make that, Erin? We all want the recipe!)  The beat goes on The beat goes on Still more music followed, and went on until the early morning hours, long after we'd gone home to bed. We would've stayed longer, but Ray had another festive event to attend the next day—a car show in New Hudson—and he wanted to be up by 4 a.m., about the time things wound down at Creekfest. Once the weekend was over, I asked Valerie (who twenty years ago declared herself Creekfest Queen) for her thoughts about this year and all the years leading up to it.  A best-ever moment A best-ever moment "For one reason or another, each Creekfest is the best ever," she says. "Sometimes I've had to stretch a bit to say that, but each year has its best-ever moments, this year included." Every year also has its share of "oh, s**t" moments, this year included. Like when Valerie lost her birthday kazoo at the ducky race and dropped her iPad into the creek. But by last Tuesday, when I touched base with her, The Queen was chipper as ever and recalling the best-ever moments as well.  Dogs and kids add to the fun Dogs and kids add to the fun "The music, the kids, our kinship and love, the camaraderie. Even the dogs keep things fun and lively." Another highlight: Creekfest's first-ever silent auction, which helped defray expenses—higher this year due to some necessary repairs and replacements. "We were ravaged by rodents last year," says Valerie. "They took down our inverter for the solar, the generator that pumps our water, the golf cart. They got into the wiring and trashed things."  Until next year, Peace Out! Until next year, Peace Out! All things considered, though, this year was the best ever. And next year? Better still. Do you have an annual event with its share of best-ever moments? What makes you look forward to it? More scenes from Creekfest . . .

11 Comments

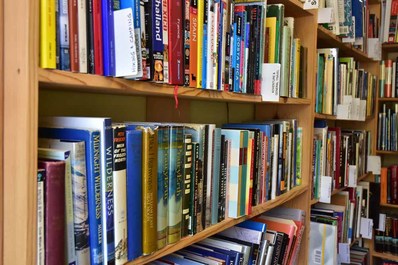

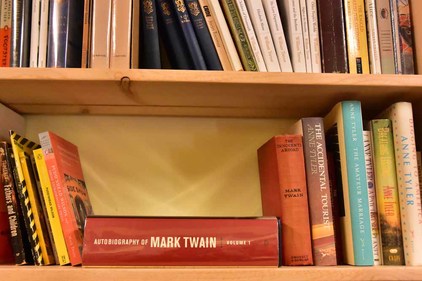

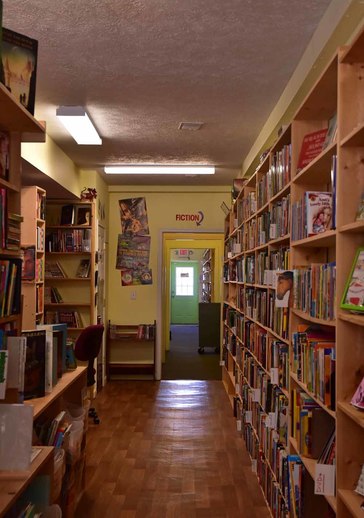

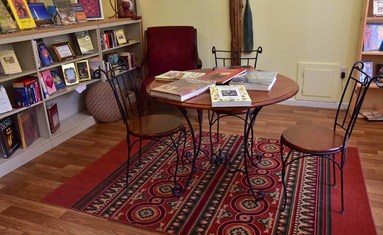

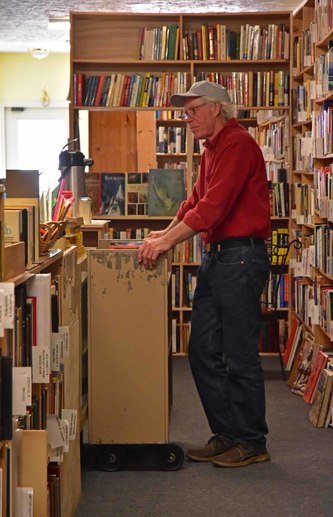

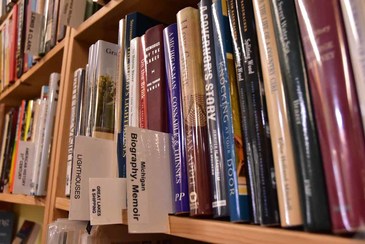

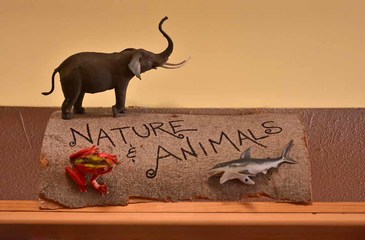

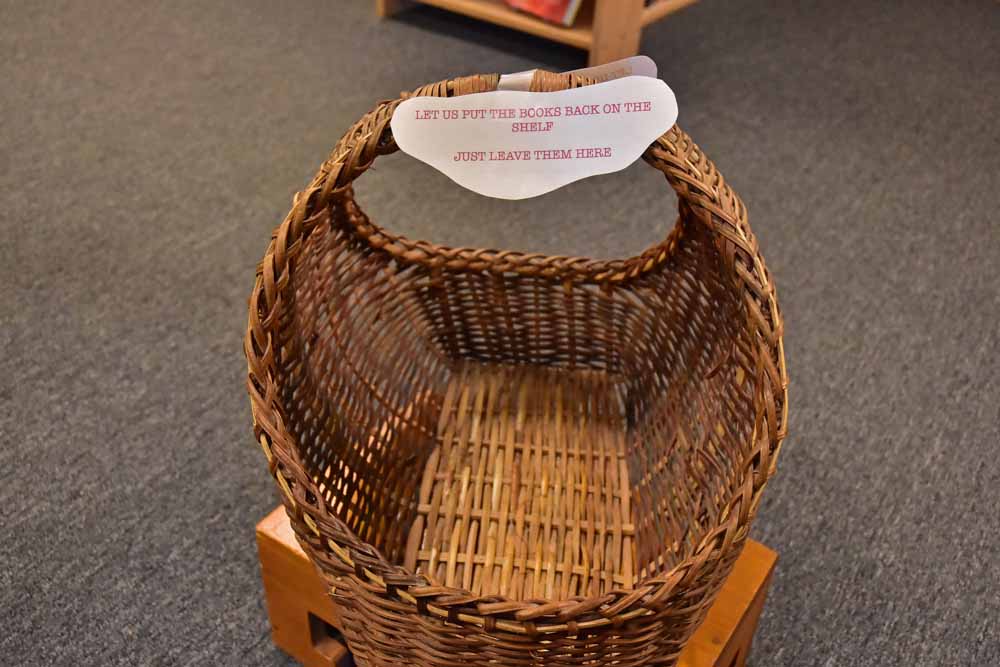

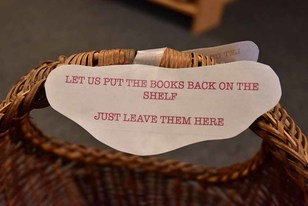

Bay Leaf Books was known for its well-curated selection of high-quality used books Bay Leaf Books was known for its well-curated selection of high-quality used books Book lovers in our community felt disappointed—and frankly, guilty—when word went around last winter that Bay Leaf Books was closing. The store, filled with an assortment of carefully selected, meticulously organized, high-quality used books, had graced Newaygo's main street for more than three years, after moving from nearby Sand Lake. We all loved having a bookstore in town. Maybe we just didn't love it enough. That's where the guilt came in. If only we'd visited more often, bought more books, might that have made a difference?  Could we save the store book by book? Could we save the store book by book? As the initial shock wore off, our conversations turned from what we should have done to what we still could do. Was it too late to rescue the shop? If not, how could we do it? Most of us were still thinking in terms of buying more books—maybe even pledging to purchase a certain number a month.  John Reeves had a bigger idea: Buy the whole store John Reeves had a bigger idea: Buy the whole store John Reeves had a bigger idea: buy the whole, honkin' store. He paid a visit to owner Gabe Konrad, who told him recent life changes had prompted the decision to close the brick-and-mortar store and concentrate on his mail-order book business. The two men kicked around some numbers, and John left, excited with the idea of recruiting friends to go in together on the store.  Marsha and John Reeves at Flying Bear Books Marsha and John Reeves at Flying Bear Books "It turned out only one was interested," John says. So John, his wife Marsha and the friend pooled their money, and Flying Bear Books was born. It took some doing for Flying Bear to achieve liftoff, however. "In my mind, I was going to buy a bookstore, turn the lights on, open the doors and sell books," John recalls, laughing now at the thought.  Shoppers are welcome to linger over books in this seating area at the front of the store Shoppers are welcome to linger over books in this seating area at the front of the store "We were thinking, we'll move a little furniture, create a comfortable place where people can hang out," adds Marsha. "As we got into it, it was clear there was more and more that we wanted to do. That's when it struck us that, oh, this is a big project!" The biggest "to-do" was entering all the books into a database, to keep tabs on what kinds of books are selling best. Previous owner Gabe, who's been selling books through catalogs and specialty shows for more than 20 years, knew the store's inventory inside and out. John and Marsha, on the other hand, were not only getting acquainted with the store's contents, they were brand new to the book business. Unlike "book guy" Gabe, "we're just readers," says Marsha.  Rod Geers and John at work, cataloging books Rod Geers and John at work, cataloging books John researched software packages, decided on one, and started entering books, with the goal of having 10,000 cataloged by the store's March 1 opening. The process turned out to be so time-consuming, only 2,000 had been entered by then. While John focused on the inventory, Marsha coordinated painting, cleaning, rearranging and signing up artists to sell their work in the shop. Neither labored alone, though.  Rod Geers Rod Geers "We put out the word that we could use any help we could get, and people showed up weekend after weekend," says Marsha. "It was so heartwarming. I just felt embraced by the community." Two helpers, Rod Geers and MaryAnn Tazelaar, stayed on to work part time. Other friends have volunteered to pitch in when John and Marsha go on vacation.  The store still has sections on a surprising number and range of topics The store still has sections on a surprising number and range of topics The new bookstore owners are committed to maintaining the same high standards that Bay Leaf Books was known for, and the store's organization is the largely the same. "Gabe's thinking was, if he had three books on a topic, he would create a section for it with a shelf card. That was his criterion," says John. "So we don't throw cards away, we keep them even if we might run out of the three books in that area, because I might go to a sale and find three more books on that subject."  The strategy pays off in sales, he adds. For example, "one young lady in her twenties came in looking for books on how to survey land. It turned out we had four books on surveying. She bought three."  Marsha arranges books in the Indigenous Literature section Marsha arranges books in the Indigenous Literature section The Reeveses did move the military section from the front of the store to the center "to soften the entry," says John. They also hope to increase the indigenous section, with a special sub-section for Anishinaabe literature.

As for other directions, time will tell.  Even remembering to flip the OPEN sign is a learning process for a new business owner Even remembering to flip the OPEN sign is a learning process for a new business owner "For me, it's a learn-as-you-go process," says John. "Every day I'm learning something new about books or how they're categorized." Or, he says, popping up and rushing to the front window, "learning to turn over the OPEN sign." The biggest surprise so far: "It's a business, and I have to start thinking of it like a business." He's brainstorming ideas to draw in customers—perhaps a book club or a more informal monthly get-together where people just talk about whatever they're reading. He'd also like to find ways of supporting local authors and working with schools and community groups.  Section sign in the store Section sign in the store All of which makes it clear this undertaking is not just a business proposition to its new owners.  Be on the lookout for bears throughout the store Be on the lookout for bears throughout the store For Marsha, holistic nurse with an interest in all aspects of healing, changing the store's layout and getting it working in a different way was "a form of healing." And, she adds, "I know that there's healing that goes along with learning, and there are a lot of opportunities for people to learn here."  New sign, new store, new direction for its owners New sign, new store, new direction for its owners What's more, owning the bookstore is just plain fun—way more than John and Marsha expected. "Every day, John comes home with a story about something funny or about helping a kid who came in with a cool question," says Marsha. "It's really a delight." Flying Bear Books is located at 79 State Road in Newaygo. Hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Phone: 231-414-4056.

Bay Leaf Books still operates as an online bookseller. Visit here.  Christa Smalligan's fairy house creation: Stump Studio Christa Smalligan's fairy house creation: Stump Studio Sunshine smiled on the Enchanted Forest, AKA Camp Newaygo, for at least part of last Saturday, but Sunday's downpours had fairy-folk scrambling to take shelter under toadstools. No worries, though. Quick-thinking Camp Newaygo staffers whisked gnome homes and pixie palaces out of the wet woods and into drier hiding places, where twinkly lights made fairy-house hunting just as enchanting.  Camp Newaygo's Lang Lodge Camp Newaygo's Lang Lodge The occasion was the two-day Enchanted Forest walk, a fundraiser for the independent not-for-profit camp located on 104 acres along a chain of lakes in the Manistee National Forest region of mid-western Michigan.  Sun and Moon by Sally Kane and Zoe Erin Hance Sun and Moon by Sally Kane and Zoe Erin Hance Last year's Enchanted Forest event was a great success, and this year's appeal to artists and craftspeople to create and donate fairy houses again yielded a fanciful assortment of tiny abodes—forty-seven in all.  Wild West Nest by Fremont Middle School Art Club Wild West Nest by Fremont Middle School Art Club It's always fun to see what imaginative people use to craft these dwellings: tree stumps, gourds, clay, copper wire, twigs, feathers, tin cans. One of this year's creations was made from a cowgirl's boot. Another had a hornet's nest worked into the design.  Camp Newaygo's Wetland Trail Camp Newaygo's Wetland Trail Ray and I got a close look at many of them when we helped hide the homes in the woods and along the Wetland Trail early Saturday morning. Then, as visitors began arriving and heading out with trail maps, we made the rounds again to watch them discover the little houses. We had fun watching visitors' reactions to our own creations, too, both the fairy house and the story that went along with it.  Summer House by Valerie Deur Summer House by Valerie Deur "We were so excited to see families outside and enjoying the houses that were hidden on the trails," said Christa Smalligan, the camp's Events and Facilities Director. "Camp Newaygo is a great place for families to enjoy activities together. I heard many kids found some fairies in the woods." If you missed out on the enchantment—or if you'd like a chance to relive it--here's a look at more of the fairy houses and the weekend's fun. And if you'd like a fairy house for your very own, all the houses pictured here--and more--are available for purchase on ebay through May 8. Proceeds help fund the camp's youth and family programs as well as renovations to facilities such as the Foster Arts and Crafts Lodge.  Tim Motley Tim Motley In January, Ray and I spent a delightful hour or so viewing the latest work of photographer Tim Motley at an exhibit and reception at Artsplace in Fremont. Tim, who has made a living as a commercial photographer for thirty-seven years, recently changed direction to concentrate on fine art abstract photography. As I listened to Tim discussing his inspirations and techniques with gallery visitors, it occurred to me that HeartWood readers might also be interested in what he had to say. Though I had already peppered him with questions the night of the reception, he graciously agreed to answer still more questions for this Q&A. I'm always fascinated when someone who's been successful following one path decides to take a chance and turn a different direction. You mentioned that your shift from commercial photography to fine art photography was something you'd been thinking about for a while. What made you decide it was the right time to make the move? It was one of those things where you're kind of gently pushed. I started out in fashion in back in the eighties, moved into high-end weddings, and then when the economy went down, my weddings went from fifty a year to four. Because of the economy and so many other photographers out there, I decided to go into fine art world. I had done some fine art work back in the nineties, but it really didn't go anywhere. This body of abstract work that I'm doing now, I'm very motivated to get it out there, get into galleries and museums. I look at this as my legacy. Was your previous fine art work similar in any way to the work you're doing now? It was very different. Quite a bit of it was travel photography—a lot of images from Italy. The rest of it was just fine-art things that I'd shot off and on through the years, like Tibetan monks. I have photographed events all my life, and after a while, with the events, I started getting little fine art pieces. And in the nineties, I was in an artist's co-op. We had a gallery in South Haven and we all sold our artwork. That kind of dried up when my weddings took over. Where did the initial idea for this new work come from? About three years ago, I was photographing a dance rehearsal. I was starting to get really bored with it, because the dancers would get up and move around, and then they'd sit down and talk about it. You could be there for four hours without much happening. So I started shooting abstracts of the dancers in the dance studio under fluorescent lighting and getting some interesting results. That's where it really took off. I thought, if I take the concept to my own studio where I can the control lighting and background, I bet I could get some remarkable results. How much experimentation did it take before you arrived at a process that would produce the results you're after? Actually, I'm still in the experimenting stage. But probably about a year into it, I started feeling confident and knowing I had something here to really treasure. After that, with each shoot, I continue to learn something. It just evolves. There's really no hard-and-fast rules that I use in this, with the exception that generally I use one light and one person, and they have to move. Those are the only requirements. I've been doing this for about three years, and as I go along my techniques shift and change a little day by day. One of the really neat things about this is, I felt like I had learned everything there was to learn as a photographer, and now all of a sudden this abstract world has opened up a whole new world for me. I'm learning much more about photography. For photography enthusiasts, can you say a little about the techniques you use in this work? We set up one light, and I have the model standing on the floor under the light. We put some music on. The music is very important; we try to put on music that they love to move to, dance or yoga or whatever, and then we start to shoot, using low shutter speeds. Usually the shoots last an hour only, because after that the model is exhausted and so am I. It's a real short time, but it's filled and compacted with energy like crazy. Every model that comes in brings something different to the shoot. Some are professional models, some are dancers, and I've had a number of actresses come in. Each person brings a little something different each time, be it through their personality or through their talent. That contributes to the difference in each shoot. How many images do you typically take to produce one of these pieces? In one session, we will shoot anywhere from 500 to 800 images. There's a whole lot of shooting going on. Usually out of that 500 or 800, I can come up with five or six really good pieces. Then I'll narrow that down to maybe one. The rest of it is just exploration. You mentioned that your wife, Patty Caterino, does the printing and any post-processing that's involved. Can you say a little about that process? Oh, absolutely. Being that I shoot everything digital, there's a lot of latitude with any of the images. Basically all we do with the images is what you would do in a traditional darkroom. The lights are darkened, maybe a little contrast and saturation, but that's it. All of the abstract work is actually done in the camera. After we shoot, quite often I'll spend a few days evaluating the images, and then I'll pull maybe 20 or 30. My wife will sit down with me, and then she and I will go over them. Her knowledge in the computer is far beyond anything I could ever do. She starts making little adjustments, and she'll see things in her mind's eye, and from that all of a sudden other things start coming out of the picture. In fact, the one picture that was like the main picture of the whole Artsplace show showed a blue body walking out of frame. That was a picture that I just breezed right over. My wife found it and said, "Oh, let me take a look at this," and she made a couple of minor adjustments and all of a sudden the picture took on a whole new life. I'm basically a photographer. I work the camera, but I don't work the printer. I don't have experience in that field. My wife and I really make a very good team. We've been together since 1995, and we have a good cohesion, where with what I shoot, she makes my images so much more beautiful. She's an artist in her own way. Anything she has an interest in, she can pick up some books, read them for about two weeks and then master whatever she wants to do. She's done everything from welding to glass mosaic work. She used to do a lot of oil painting on my photographs, where she'd take a black-and-white image and hand-color it. She has a phenomenal touch. She's very, very artistic. The things that we do together let her use that talent. What do you feel you're expressing in this new work? These abstracts kind of parallel my life. In the old days, when I was out there photographing events, my life was wide open to everyone, and people knew what was going on in my life. Now I'm much more reclusive, and my work is shifting with my personal life as well. Part of the idea behind the abstracts is, the body will have no clothing, no jewelry, simply because I don't want to depict this society. I would like those images to be as timeless as they can be. My personal feelings are, the more I see of society, the less I want to be a part of it. So the abstracts kind of play along with that, and are something different that no one else does. And this work speaks to me. It really does. And it stimulates me. I had reached the point a while back where the work just did nothing for me. All I did was make pretty pictures, but I couldn't feel anything coming from it. When I do these abstracts now, there's a feeling I get, a sense of accomplishment, definitely a sense of mystery. Sometimes I don't even understand what I'm getting, but I love what I'm doing. So I just continue down that path and see where it takes me. Every piece that you see of my work is a part of me. I feel that connected to it. I think for the first time in my life, I truly do feel like an artist, and I wouldn't trade that feeling for anything in the world. Where do you find inspiration? In the early days when I was shooting a lot of fashion, some of the fashion photographers like Helmut Newton and Richard Avedon inspired me. Nowadays my references that I use for studying are Picasso, Matisse, de Kooning. I really do see life in an abstract way now, and this is all I really see photographically, too. I study art all the time. If I'm not shooting or working on pictures, I'm studying other artists' work just trying to be inspired by it, analyze it, see how it can come into my work. How did you first get started in photography? Back in the 1970s, I got a camera and started photographing my sons. One day I was shooting one of my sons in the living room, and I did something different with the lighting, and it was the most different picture I'd ever made. That really inspired me. I was bitten by the bug then, and I took off with photography. I started reading everything could get my hands on about photography. I was a magazine junkie. I bought every magazine I could get on photography and devoured it. I dabbled in it until about 1985, when I met a guy at a camera shop who had a little studio in a warehouse in Grand Rapids. He said, "I'll tell you what, you come in and help me with my rent, and I'll teach you how to use studio lighting." I was with him for two months; then he took on a couple of other photographers because he wanted to lower the rent even further, and the place was too small for all of us. So in the same building, I built my own studio. I had close to 2,000 square feet that I only paid $200/month for. I was there for fifteen years in that building, shooting fashion and weddings and portraits. Then my wife and I met in '95 and the place we live now came up for sale in '97. Where we live now is in a little area called Tallmadge Township, about fifteen miles outside the city of Grand Rapids. We actually own an old town hall, and that's what my studio is in. In back of the town hall is our house. One benefit of shooting the abstracts in the studio is that it keeps me home more often. What suggestions do you have for anyone who's starting out in photography or who's been dabbling in photography for a while but wants to get better at it? The one thing I could suggest is, you have to have a very strong drive. You have to be dedicated to it and you have to be focused on it. To go the route that I've gone, you have to work at it 24 hours a day. Once I got into photography and started professionally, it was like there was nothing else that went on in this world to me except my photography. Are there other directions you'd like to take this work in the future? One of the ideas we're kicking around now is tying my abstracts in with cancer patients. One of the models who's been in probably three or four times to do these abstract nudes is a breast cancer survivor. She's 57 years old, and she's got scarring, and it's obvious what she's been through, and we made some very beautiful artwork of her. Further down the road, if we can find a patron to bankroll this kind of project, I'd like to make beautiful abstracts—nudes or portraits—with cancer survivors and have them displayed in a hospital. Is there anything else you'd like to add?

The show at Artsplace led to a contact in Ludington, and I'll be putting on a show at the Ludington Area Center for the Arts in 2018. If the news of the day has been getting you down, here's one bulletin that's guaranteed to inspire:  Fairy's eye view of Camp Newaygo Fairy's eye view of Camp Newaygo FAIRYLAND, Newaygo County (March 1, 2017)—In spite of last year's housing boom in the Enchanted Forest (also known as Camp Newaygo), officials report a serious shortage of sprite-sized housing.  Among last year's fairy house creations: "Eric's Abode" by Eric LeMire Among last year's fairy house creations: "Eric's Abode" by Eric LeMire "Thanks to the artistry of local supporters, the fairy homes that sprang up in our forest last year were so attractive, they were all immediately occupied by pixies, gnomes, sylphs and all manner of tiny creatures," says Elvira Elf, housing coordinator. "We’re expecting an influx of fairy folk soon, as they return from their winter homes down South. We're asking everyone to pitch in again to create a forest full of houses to welcome them back." After receiving the news, fairy-house builder Wildwood Ray was spotted heading for his workshop with an armload of mysterious materials. "This is one call to action it's impossible to ignore," he said.  "Sue's Cabin" by Sue Barthold "Sue's Cabin" by Sue Barthold Bet you can't ignore it either! So start gathering twigs, moss, stones and anything else that strikes your fancy, and get busy creating. Houses are due April 15 (you can drop them off at Camp Newaygo or call 231-652-1184 to schedule a pick up). Guidelines are listed below.  "Rustic Retreat" by Ray Pokerwinski "Rustic Retreat" by Ray Pokerwinski The fairy houses, gnome homes, pixie palaces and elfin abodes will be hidden in the forest surrounding the camp, and during the Enchanted Forest Event, April 29 and 30, visitors can wander the woods with a trail map, searching for the houses and trying to spot their secretive inhabitants. Cookies and punch will be supplied for house-hunting fortification, and for an additional fee, young visitors will have a chance to create their own handiwork at a craft table. All the fairy houses will be auctioned on eBay afterward, so you can pick out a favorite to take home. (Don't forget to make a wish for a fairy to come along with it!)

Camp Newaygo offers campers and community a variety of experiences Camp Newaygo offers campers and community a variety of experiences Camp Newaygo is an independent, not-for-profit camp located on 104 acres along a chain of lakes in the Manistee National Forest region of mid-western Michigan. In addition to offering a girls' residential summer camp and a coed day camp, the camp provides year-round community events: dinners, girlfriend getaways, winter sleigh rides and more.  "Green Glass Cottage" by Eileen Kent "Green Glass Cottage" by Eileen Kent Last year, organizers hoped the first Enchanted Forest event would bring in twenty-five to thirty little dwellings. They received forty-two houses, and a total of 627 visitors toured the forest over the two days. Here are this year's guidelines for building your fairy house:

The Enchanted Forest tour is April 29 and 30, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Cost is $7 per person or $25 per family of four. The make-and-take craft table will be available from 10 a.m. to noon on the 29th, for an additional charge. No advance registration necessary; please pay at the door. For additional inspiration, see these posts on last year's Enchanted Forest event:

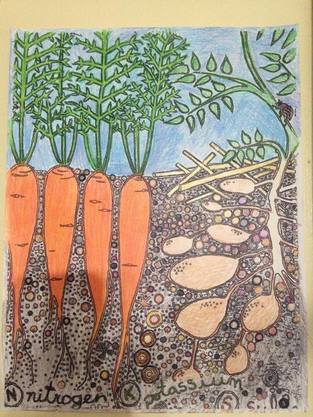

Fairies and pixies and gnomes, oh, my! The News from Lake FaeBeWell Exploring the Enchanted Forest Valentine's Day is over, but can't we all still use some love? I think we can, so I'm offering quotes about love in this installment of Last Wednesday Wisdom. And because HeartWood and I both celebrated birthdays this month (guess who's older), I'm throwing in some about age and experience, as well. In the spirit of love and celebration, I'll even give you a treat at the end: photos from a recent concert and exhibit by local luthiers (stringed-instrument makers). There are two basic motivating forces: fear and love. When we are afraid, we pull back from life. When we are in love, we open to all that life has to offer with passion, excitement, and acceptance. We need to learn to love ourselves first, in all our glory and our imperfections. If we cannot love ourselves, we cannot fully open to our ability to love others or our potential to create. Evolution and all hopes for a better world rest in the fearlessness and open-hearted vision of people who embrace life. -- John Lennon Love does not consist of gazing at each other, but in looking outward together in the same direction. ― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Airman's Odyssey The great thing about getting older is that you don't lose all the other ages you've been. -- Madeleine L'Engle How many slams in an old screen door? Depends how loud you shut it. How many slices in a bread? Depends how thin you cut it. How much good inside a day? Depends how good you live 'em. How much love inside a friend? Depends how much you give 'em. ― Shel Silverstein Tell myself: Trust in Experience. And in the rhythms. The deep rhythms of your experience. -- Muriel Rukeyser No matter what you're feeling, the only way to get a difficult feeling to go away is simply to love yourself for it. If you think you're stupid, then love yourself for feeling that way. It's a paradox, but it works. To heal, you must be the first one to shine the light of compassion on any areas within you that you feel are unacceptable. -- Christiane Northrup Imagination has no expiration date. -- Paula Whyman, author, in article on debut authors over age fifty, Poets & Writers magazine, November-December 2016 Love is a canvas furnished by nature and embroidered by imagination. -- Voltaire We get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that's so deeply a part of your being that you can't even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more. Perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless. -- Paul Bowles If you have only one smile in you, give it to the people you love. -- Maya Angelou If I had known when I was twenty-one that I should be as happy as I am now, I should have been sincerely shocked. They promised me wormwood and the funeral raven. -- Christopher Isherwood  Feed a starving artist! Feed a starving artist! What do farming and art have in common? A lot more than you might think, say Mike and Amanda Jones of Maple Moon Farm in Shelby, Michigan. To underscore the connection, they're sponsoring a FEED THE STARVING ARTIST contest with the theme, "Local Food and Local Farms" and a prize of a $250 gift card to the farm.  Amanda Jones of Maple Moon Farm Amanda Jones of Maple Moon Farm "The idea was really born out of a desire to increase community connections," says Amanda. "One of the reasons we farm is, we really enjoy having that direct relationship with the people who eat our food. Another element is, we feel that we ourselves bring an artistic element to farming. We wanted to draw on that bond with other artisans, whatever their art form, to create connections and a stronger community."  The Joneses with freshly-picked greens The Joneses with freshly-picked greens Artists and artisans have until March 4 to register, either by emailing Mike and Amanda at maplemoonfarm@gmail.com or by stopping by their booth at Sweetwater Local Foods Market in Muskegon, Saturdays from 9 a.m. to noon. Anyone planning to enter needs to let the Joneses know the type of art and the size of the piece, so they can plan for enough display space at the market on March 11, when voting will take place. If registering by email, please send a photo of the entry.  Amanda assists a farmers market shopper Amanda assists a farmers market shopper The entries themselves may be dropped off at the farm or brought to the market on the 11th, when market shoppers will cast ballots to select a winner. "We just ask that anyone bringing their art on the 11th have it there by 9 a.m., when the market opens," says Amanda.  Farming from the heart Farming from the heart Entries of all sorts are welcome, she adds. "When someone is practicing something from the heart and really putting an element of themselves into what they create, we view that as being an artisan. We wanted to leave the definition broad to be as inclusive as possible." The only criterion is that all works should be related in some way to the theme of local food and local farms.  Harvest time Harvest time The winner will be announced at the market's close on the 11th and will also be featured on Maple Moon's Facebook page. "The winning piece, we will keep in exchange for the gift certificate," says Amanda. Other entries should be picked up at the market after results are announced on the 11th.  Maple Moon produce at the market Maple Moon produce at the market For budding artists and coloring enthusiasts of all ages, there's a coloring contest, too! Coloring pages are available from Mike and Amanda on market days at Sweetwater Market. Market shoppers will also vote on coloring contest entries on the 11th, and the winner will receive a generous gift basket from the farm.  At market At market The couple hopes the contests will forge new connections between local food producers, artists and other members of the community. "We're hoping this will draw in people who haven't been connected with their local farmers market and that others who identify as artisans will connect with this local resource and see the parallels in what we do. Our community thrives when people are able to do what they truly love. It makes us happier people and benefits everybody as a whole. If we are able to support each other in doing what we love, it's a win-win for everybody."  All fresh and local All fresh and local Love is a big part of Mike and Amanda's approach to farming, says Mike, who grew up in Newaygo County family that gardened and raised animals. "We believe growing plants is an art form more than a job. We treat every plant with respect to get the best-quality produce . . . Everybody talks about their grandparents' garden and how they raised the best-tasting tomatoes. There's a reason for that: the plants were getting all the love and attention they had. When you're putting that kind of attention into the food, you get the best quality."  On the farm On the farm Maple Moon has used organic growing practices from the beginning and is currently certified organic. Though the farm's output has grown in the seven years since its beginning, Mike and Amanda want to keep it small enough that they can still be hands-on, rather than hiring other people to do the work.  Heirloom tomatoes Heirloom tomatoes "If we stay small, we can have more control over how plants are loved," Mike says. "Our primary goal is to grow things that taste the best." The Joneses grow "most vegetables you can think of," including "lots of heirloom tomatoes," but specialize in greens and herbs, both culinary and medicinal, says Amanda, who grew up in suburban Detroit, but took an interest in food and farming in her late teens. She arranged to work for six weeks on Nothing But Nature farm in Ohio and ended up staying more than three years.  Spinach Spinach Consumer interest in organic and locally-produced and foods is on the rise, but with those foods increasingly available in supermarkets, many shoppers don't visit farmers markets. Amanda wants to remind them there are still good reasons to buy directly from growers.  Good food! Good food! "You're not only getting fresher food, but you're also creating a relationship with the person," she says. "I know our food has to be good and clean, because I know the people who are going to use it. I see their children. I've watched babies grow up on the food. Sometimes when I'm out in the field, harvesting or working on a crop, I think of the people who come to the market who love it. That creates better connections and better health for everyone involved." Sweetwater Market operates at the Mercy Health Lakes Village, 6401 Prairie St., Norton Shores, and is open Saturdays from 9 to noon. Maple Moon Farm is located at 1224 S. 144th St., Shelby, Michigan. Phone: 231-861-2535 Photos courtesy of Mike and Amanda Jones

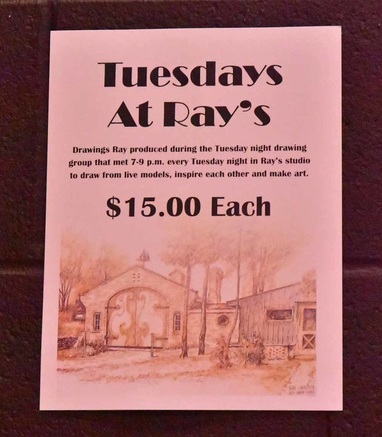

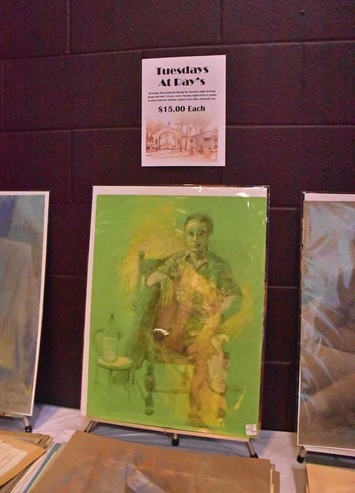

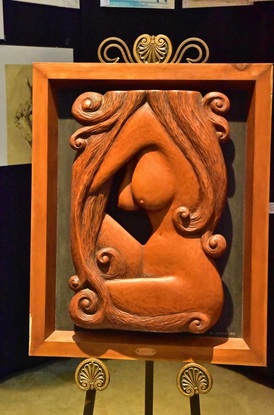

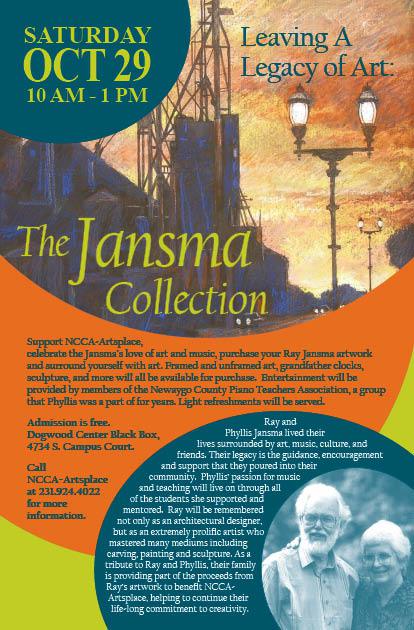

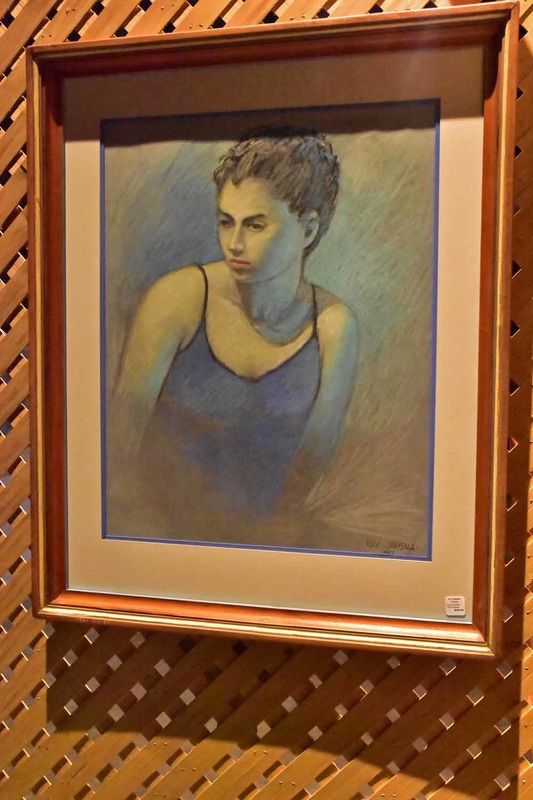

What difference does a difference make? At a recent memorial for a friend and teacher, the speaker posed that question for all of us to consider as we thought about the person whose death we were mourning and whose life we were celebrating.  The sale at the Dogwood Center's Black Box. Photos of the Jansmas were projected on the large screen during the sale. The sale at the Dogwood Center's Black Box. Photos of the Jansmas were projected on the large screen during the sale. The question came to mind again last weekend when we attended "Leaving a Legacy of Art: The Jansma Collection" at the Dogwood Center for the Performing Arts in Fremont, Michigan. The art show and sale commemorated the lives of longtime Fremont residents Ray and Phyllis Jansma, whose lasting influence on Newaygo County's cultural scene is incalculable. Phyllis was a cellist and music teacher, Ray an architectural designer and artist who painted, sculpted and carved wood. As a tribute to this remarkable couple, their family offered some of Ray's artwork for sale, with a portion of the proceeds to benefit Newaygo County Council for the Arts-Artsplace.  Lindsay Isenhart with a grandfather clock made by Ray Jansma Lindsay Isenhart with a grandfather clock made by Ray Jansma Before the sale, I spent some time with Lindsay Isenhart, program coordinator and curator of the Ray and Phyllis Jansma Gallery at Artsplace. A good friend of the Jansmas, Lindsay worked closely with Ray Jansma to produce a book, Ray Jansma: Designer (Blurb, 2011), that chronicles his career and archives many of his artistic works.  Some of Ray Jansma's drawings from the Tuesdays At Ray's gatherings were also for sale Some of Ray Jansma's drawings from the Tuesdays At Ray's gatherings were also for sale "The Jansmas were a pivotal influence on my life," Lindsay told me. "I started going out to their house for Tuesdays At Ray's—a Tuesday night drawing group—when I was fourteen years old. At that point in my life, I was a latchkey kid. I could have gone a very different way, but once I started drawing, my whole direction in life changed."  The weekly gathering wasn't a class; there were no lectures or formal critiques, just a bunch of local artists and art enthusiasts getting together to practice life drawing and share their creative energy. "I had never seen a cluster of artists working together. Just getting together to do art," recalled Lindsay, who went on to be one of the first recipients of the Ray Jansma Scholarship for Visual Fine Arts, through the Fremont Area Community Foundation, and to study fine arts and graphic design at Kendall College of Art and Design in Grand Rapids and Accademia di Belle Arti in Perugia, Italy. "Through the Tuesday nights, I got to know Phyllis, and on a regular basis went out to what they called Tea Time at the Jansmas," Lindsay said. "People could show up from anywhere at their house during tea time. Phyllis would regale us with stories and talk about politics, and Ray would take me out to his studio afterward."  The Jansma home The Jansma home The Jansmas' talents and personalities drew people to them, but their home was an added attraction. Located on a winding road north of Fremont, the house—which Ray designed in the early 1950s—started out as a modest 975-square-foot split level. But as Ray's career grew, so did the house, with additions reflecting the varied styles of his architectural design projects. On one end is a master bedroom suite where the centerpiece was the magnificent carved angel bed offered for sale at the recent event.  The tower The tower A tower rises from the middle of the house, looking like something from a storybook. Indeed, guests sometimes felt they were "visiting another world," said Lindsay. "It was like Alice in Wonderland. I got to go to this fairytale place where we were surrounded by art, music, and everything you could imagine to play with." Like the house, Ray's studio was out-of-the-ordinary, decorated with architectural elements from some of his design projects. One side of the studio was originally used for building a sailboat—a 32-foot Tahiti ketch christened the Maid of Ramshorn, which Ray and Phyllis sailed around Lake Michigan and Lake Huron (and Ray sometimes used as a floating office for design jobs in port towns). Once the boat was finished and launched in 1975, the former boat shed became a working space for various art projects, both Ray's and other artists'.  "He'd share whatever he had going on, share his studio space, encourage others to come and work there," said Lindsay. The list of working artists who have been influenced by Ray is long and varied and includes Ann Arbor potter Autumn Aslakson; Stratford, Ontario-based illustrator and graphic designer Scott McKowen; ; New Mexico painter Jack Smith; multimedia artist James Magee of El Paso, Texas (who also paints as Annabel Livermore) and many others.  "He inspired so many artists because he was always working," said Lindsay. "His work ethic was amazing. He didn't watch TV, didn't golf. He'd be in his studio, working on a project or out sketching barns or downtown businesses or putting in time for our organization. He would come here to Artsplace at least once a week and participate, whether it was just helping paint a sign or helping teach a class, he was hands-on involved." Meanwhile, Phyllis inspired a long line of musicians, not only as a piano and cello teacher, but also through the Chamber Music for Fun program she initiated at Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp in Twin Lake, Michigan.  Daughter Jennifer Jansma Chiles (in green sweater) was on hand to answer questions and reminisce with family friends Daughter Jennifer Jansma Chiles (in green sweater) was on hand to answer questions and reminisce with family friends The Jansma children, too, benefited from the creative environment their parents provided. Tim became a violin, viola and cello maker, Jon a chemical engineer for GE, and Jennifer a piano technician who decorated her Ray-designed home with ornamental trim she carved herself and paving stones she hand-cast.  Front door, Jansma home Front door, Jansma home "I've never met a family that has made such an impact," said Lindsay. "And to be found in such a tiny little community is a rare thing." The Jansmas made a difference. And what a difference that difference made! Who has made a difference in your life? In your community? What can you do to keep their legacy alive? As you consider these questions, take a look at more of Ray Jansma's artistry.

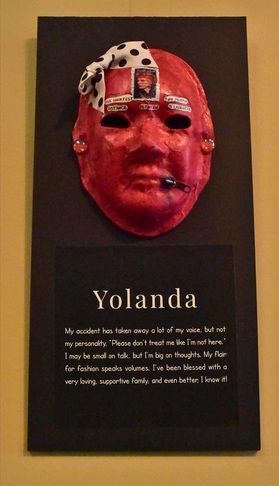

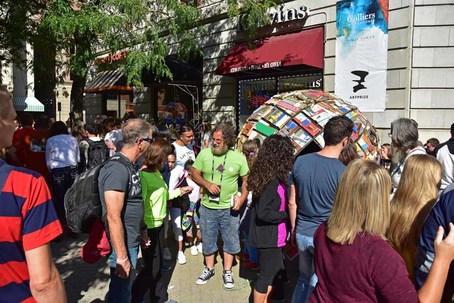

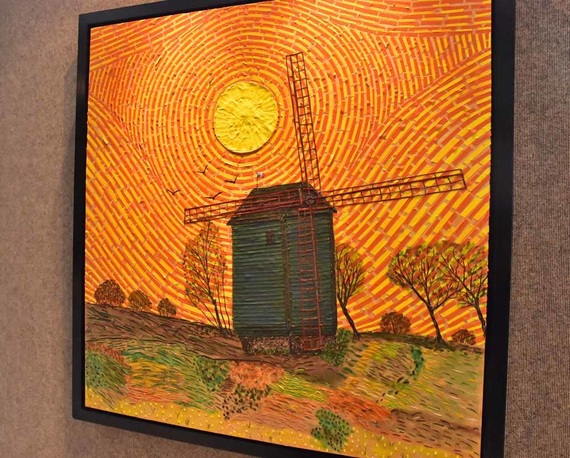

If I invited you to come with me to the "most attended public art event on the planet," where do you suppose we'd go? Paris, perhaps? New York? Some quaint California town?  ArtPrize visitors take in one of the installations in DeVos Place ArtPrize visitors take in one of the installations in DeVos Place What if I told you that the event takes place here in West Michigan? It's called ArtPrize, and it draws some 400,000 visitors to Grand Rapids over a nineteen-day period in early autumn. Unless you've experienced ArtPrize first-hand, grasping its scope, scale and concept can be mind-warping. When I try explaining it to out-of-towners who've never attended, they grope for comparisons. "So it's a big art fair, like Ann Arbor's," they venture. No, it's not like that.  An artist draws a crowd at ArtPrize An artist draws a crowd at ArtPrize "So it's some kind of festival of the arts, with performances, exhibits and activities?" No, Grand Rapids has one of those in the spring, but that's not ArtPrize.  ArtPrize fosters a festive feeling ArtPrize fosters a festive feeling Maybe this will help. In a recent conversation, some of my hiking friends were comparing notes on their visits to this year's ArtPrize. Peg, still euphoric over her day-long excursion, said, "There are no carnival rides, there's nothing to buy, yet it feels like a festival."  Where else can you see so many people gathered just to view and discuss art? Where else can you see so many people gathered just to view and discuss art? Anita added in an almost reverent tone: "And all these people come, just to look at art!" Still not getting it? Let's try some facts and figures. ArtPrize is an international art exhibit and competition that takes place in 170 locations—from museums and galleries to bars, bridges, laundromats and auto body shops—over a three square mile downtown area. The event is free to the public, who can vote for their favorites using mobile devices and the ArtPrize web page. Cash prizes, half of which are decided by public vote and half by a jury of art experts, total $500,000. Any artist can enter, and any space in the district can be a venue. "It’s unorthodox, highly disruptive, and undeniably intriguing to the art world and the public alike," the ArtPrize web site asserts.  "Embrace," by Marc Sijan, prompted double takes and spirited comments "Embrace," by Marc Sijan, prompted double takes and spirited comments What intrigues me most are the stated objectives of celebrating artists who take risks and promoting "examination of opinions, values and beliefs, encouraging all participants to step outside of their comfort zones." As Ray and I toured this year's ArtPrize--the eighth annual--with our friend Emily, we encountered works that made us stop and stare and others that made us stop and think. Some brought us close to tears; some were just plain fun.  One moving display featured life-sized masks made by people with brain injuries, along with each artist's personal story.  Allison Leigh Smith discusses "The Butterfly Effect" Allison Leigh Smith discusses "The Butterfly Effect" Just down that hall from that collection was "The Butterfly Effect," an installation of 1,234 handmade bronze Monarch butterflies. Artists Bryce Pettit and Allison Leigh Smith created the work to call attention to the plight of Monarchs, whose numbers have dropped dramatically over the past 20 years.  After wandering outside and crossing a bridge to the other side of the Grand River (encountering a hula-hooping guitar player on the way), we came upon an assortment of sculptures that looked whimsical at first glance. But the creatures artist Justin La Doux crafted from recycled materials peered at us from cages, making a statement about the cruelties of the illegal pet trade.  Naji (in green t-shirt) talks to visitors about his construction, "Emoh," seen behind him Naji (in green t-shirt) talks to visitors about his construction, "Emoh," seen behind him In another area, we found a crowd gathered around Loren Naji's "Emoh" sculpture/time capsule and temporary home. Constructed from debris salvaged from abandoned Michigan and Ohio homes, Emoh (Home, spelled backwards) represents wastefulness and the irony of homelessness in cities riddled with vacant houses. During ArtPrize, Naji lived in the eight-foot-diameter orb. Afterward, he planned to embark on a multi-city tour, collecting letters and discarded items from visitors at each stop. At the end of the tour, Emoh will become a time capsule, with those collected objects and writings stored inside for ten years until the capsule is opened on Earth Day 2026.  Another ambitious—but more light-hearted—undertaking was showcased down the street from Emoh. Grand Haven illustrator Aaron Zenz and his six children collected 1000 rocks in different shapes and sizes and painted faces (or facial features) on each one. The rocks were painted in matching pairs, with one member of each pair displayed outside the Grand Rapids Children's Museum, where we saw them, and the other 500 hidden around town for people to find, photograph and post on social media. (Read more about the Zenz family's project, "Rock Around" in this MLive article.) We didn't look for rocks, but we did go on our own treasure hunt, searching for work by Newaygo-area artists we know.  Eric LeMire's "Hexagonaria Percarinata" was easy to spot in the vestibule of a downtown pub. Eric used multiple layers of acrylic and poly resin to simulate the patterns of Michigan's state rock, the Petoskey stone, on a seated figure, a piece he hopes will stimulate interest in Michigan's "unique and rather exotic geological history and our human relationship with it"  And we found Kim Froese's "Bee the Queen" holding court in First Congregational Church. Kim uses bald-faced hornets' nests in her art, and this piece celebrates the role of females (insect and human) in home and family.  Tracy Cole's foil steer skull caught Emily's eye. Cole's other foil creations included a giraffe and a rhino, as well as smaller critters like the lizard below Tracy Cole's foil steer skull caught Emily's eye. Cole's other foil creations included a giraffe and a rhino, as well as smaller critters like the lizard below Kim's not the only artist who makes use of unconventional materials. This year we saw works of art created with aluminum foil, sand, duct tape and other surprising media.  ArtPrize is over now, but we still have plenty of reminders of the place of art in our lives One upcoming event, in particular, highlights the impact artists can have on the community. "Leaving a Legacy of Art: The Jansma Collection," celebrates the lives of longtime Fremont residents Ray and Phyllis Jansma, who had a profound influence on Newaygo County's cultural scene. Phyllis was a musician and music teacher, Ray an architectural designer and artist who painted, sculpted and carved wood. As a tribute to Ray and Phyllis, their family is offering some of Ray's artwork for sale, with a portion of the proceeds to benefit Newaygo County Council for the Arts-Artsplace. The sale takes place Saturday, October 29 from 10 am to 1 p.m. at the Dogwood Center Black Box, 4734 S. Campus Court, Fremont. Admission is free, and light refreshments will be served. Entertainment will be provided by members of the Newaygo County Piano Teachers Association, of which Phyllis was a member for years. I'm looking forward to the event, and I'll tell you all about it in a future post. But for now, tell me something. Where do you go to see art that inspires, elevates and even challenges you to step outside your comfort zone?

Note: You can enlarge photographs below (except for the first) by clicking on them. To return to this page from an enlarged photo, click on the X in the upper right corner of the image.  Kevin Feenstra, on the river Kevin Feenstra, on the river I've known for some time that my neighbor Kevin Feenstra is an avid angler and in-demand fishing guide on the nearby Muskegon River, but I only recently learned he's also an accomplished nature photographer. This I learned not from Kevin, who's a modest fellow, but from the bi-monthly events listing we receive from the Newaygo County Council for the Arts. There on the cover of the latest issue was one of Kevin's fish photos, and just inside, a full-page listing for "The Art of Fishing" exhibit underway at Artsplace in Fremont through August 15. In addition to Kevin's photographs, the exhibit features fine art and fine fishing craft by a number of other artists, plus collections of unique lures and fishing tackle. At the exhibit reception, from 10 a.m. to noon on August 13, Kevin will make a presentation, "Photographing a Big River." He'll also teach a two-hour class, "Photography: Nature of a Trout Stream," on Sept. 6. When I found out all of this, I wanted to hear more about Kevin's work and art and to share it with HeartWood readers. As it happened, Kevin was taking a rare break from guiding last week. When I trekked down the road to talk with him, I thought I might find him lounging on the deck for a change. But no, he'd just returned from a few hours on the river. Seems he can't stay away, even when he's not on the clock. In addition to guiding about 200 days a year, he spends another 50 to 75 days on the river fishing and photographing, he told me. Here's more of our conversation: Which came first, the fishing or the photography? Definitely the fishing first. The photography became part of it because my business is all catch and release. When you release a fish, a lot of times the people want at least a picture of it. Then, because I enjoy nature so much, I started doing more and more nature photography, which, since I'm out on the river every day, is probably the only other hobby I have time for. Another reason I got into the photography, besides the enjoyment, was that I do a lot of public speaking in the winter. When I go out and do programs, it's good to have quality photography. How did you learn each? Did someone teach you to fish? Did you take photography classes? Or are you self-taught? I started fishing when I was ten or eleven years old. At first I fished with my brother, but when he went off into the military I just picked it up more or less on my own. I read a lot as a kid, so I would go to the library and read every fishing book they had. In the beginning I was doing mostly spin fishing, but I picked up fly fishing pretty early on. My dad's great uncle died and left him some fly fishing gear, and since I was the only person that fished a lot in the family, I inherited the gear. Then I read the books and figured out how to do a little bit of fly fishing, and it took off from there. With photography, I also read a lot of books, and the internet definitely helped. I posted photos on some nature photography websites and had them critiqued. Do you see parallels between fishing and photography? Catch and release fishing and photography are both great ways to experience resources—like the rich wildlife in and around the Muskegon River—without having to harvest the animals. Another parallel is, to do either one right takes a lot of patience. You might have to wait quite a while for that creature you want to photograph to come along. For some of the photos I took of ospreys catching fish, I waited two days before one actually came down close enough. I do some snorkeling and underwater photography, and that has actually helped me with the fishing. I tie flies to imitate the various types of food the fish eat, and going underwater has helped a lot with that. Do you have favorite times of day or times of year on the river? I love being on the river in the evening most times of year, just because the light's so beautiful. But with a two-and-a-half-year-old son, it's harder and harder to do. I treasure those days when I can sneak out. The beauty of doing underwater photography is that even when the light's pretty harsh, it's fine for underwater work, because that requires a lot of light. What goes into a good nature photograph? Good lighting, obviously. When it comes to wildlife, understanding their behavior and what they're going to do. Most animals are pretty predictable—that's one thing you learn from fishing. Certain birds will be in the same area every day, and they like to feed at certain times of the day. If you can get the right lighting combined with the feeding activity, you can get a really nice image. And then seasonal things that happen on the river can make for interesting photos. The fall colors and all the salmon in the river in the fall, the winter ice, the renewal in the spring. There's always something that's beautiful. When you're out on the river, what kinds of things get you so excited you just have to grab your camera? Since our eagle and osprey populations are up, I sometimes see eagles and ospreys fighting. Ospreys taking fish is always a cool thing to see. At least a few times a year I see otter on the river. I also like colorful things like wood ducks. And this river has some turtles that are getting to be more and more rare: wood turtles and Blanding's turtles. Those are things you might see on the Muskegon that you might not see everywhere. I keep a camera with me even when I'm guiding, and sometimes I'll say, "Let me have a break." I don't take too many liberties with that, and people are very understanding. Some people may think being a river guide is a cushy, dream job, but I see you going out in all kinds of weather and I think it must have some real challenges. Right. A lot of people entering the guiding business think it's going to be a great, easy job. They quickly learn that there's a lot of hours you put into it each day—not just the guiding, but then you get home and you have to prep for the next day and return all the phone calls and emails. And for me, I tie all my own flies, so that's another hour every night. By the time everything's said and done, sometimes it's a twelve to fourteen-hour day, six days a week. What makes a good fishing guide? There's really two types of fishing guides: those who are really good at fishing and those who are really good at customer service. It's best to be a blend of the two. I always tell people that guide for me to try their best, but to try very hard to be good at the customer service end of things. Then if the fishing's bad, at least people will have an enjoyable time on the river. What about knowing the river? How do you learn the ins and outs of the river? Sheer time. I've been fishing up here since I was in my teens. Probably every possible day when I was a teenager, and when I graduated from college I was up here every day fishing. Then eventually I started guiding a little bit. The first year I was guiding maybe thirty to fifty days, but I was fishing every day I wasn't guiding. And eventually the balance tipped, and now I'm guiding way more than I'm fishing, and it's harder to take time to fish now. But it still helps to go out every day. That's my number one suggestion: If you want to be a fishing guide, you really have to put the time in. And you have to do it before you start to be a fishing guide. Because it's a lot harder to do once you're actually taking people fishing. And it's the same with photography, right? You just have to get out there and do it a lot. Right, put the time in. I tend to obsess about things that I enjoy, so I do put a lot of time in. You were single when you started your business 20 years ago, but now you have a wife, Jane, and son, Zach. Is fishing a family activity? Zach loves being out in the boat. Any fish I catch, he always wants to look at it and touch it. He attempts to help me reel it in, but we're not quite there yet. Jane likes to go out in the boat, too, but she'd rather read a book while I fish. Any parting thoughts or advice? For fishing, my advice to people is always just to keep their eyes down at the river and look into the water. A lot of times you'll see fish and can come back and catch them. One of the best ways to learn the river is the most obvious: just to keep your eyes peeled, and if you have access to a boat you can learn a lot just by driving up and down the river. The same thing holds true with the nature photography. Just keep your eyes open and watch for natural behavior. You can see more of Kevin's photographs at http://www.kevinfeenstra.smugmug.com/

|

Written from the heart,

from the heart of the woods Read the introduction to HeartWood here.

Available now!Author

Nan Sanders Pokerwinski, a former journalist, writes memoir and personal essays, makes collages and likes to play outside. She lives in West Michigan with her husband, Ray. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed